Is Europe seeing a nationalist surge?

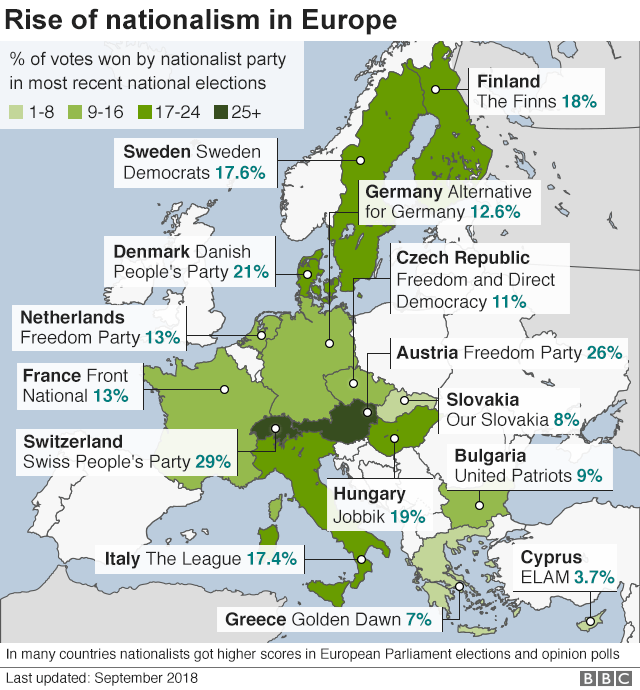

Across Europe, nationalist and far-right parties have made significant electoral gains.

Some have taken office, others have become the main opposition voice, and even those yet to gain a political foothold have forced centrist leaders to adapt.

In part, this can be seen as a backlash against the political establishment in the wake of the financial and migrant crises, but the wave of discontent also taps into long-standing fears about globalisation and a dilution of national identity.

Although the parties involved span a broad political spectrum, there are some common themes, such as hostility to immigration, anti-Islamic rhetoric and Euroscepticism.

So where does this leave Europe’s political landscape?

Italy

Inconclusive elections and months of uncertainty have culminated in two populist parties – the anti-establishment Five Star Movement and right-wing League – forming a coalition government.

Their rise from the political fringes comes in a country badly hit by the 2008 financial crisis and which then became the main destination for North African migrants.

Formerly known as the Northern League, The League has switched focus from its initial goal of creating a separate northern state to leading a country it once wanted to leave.

Their joint programme for government includes plans for mass deportations for undocumented migrants, in line with The League’s strong anti-immigration stance.

Visiting Sicily, Italy’s new interior minister and League leader Matteo Salvini said the island must stop being “the refugee camp of Europe”.

Both parties are unhappy with the euro, and with few ruling out more elections the next vote could provide a major headache for the European Union.

Germany

Formed just five years ago, in 2017 the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) entered the federal parliament for the first time.

From its beginnings as an anti-euro party, it has pushed for strict anti-immigrant policies and tapped into anxieties over the influence of Islam. Leaders have been accused of downplaying Nazi atrocities.

Their success has been interpreted as a sign of discontent with Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open-door policy for refugees.

At the height of the migrant crisis, Mrs Merkel lifted border controls and almost a million people arrived in 2015, many of them Muslims from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Despite her CDU/CSU bloc seeing its worst result in almost 70 years, last year’s elections were enough for Mrs Merkel to secure a fourth term as chancellor and form another coalition with the SPD party. For AfD, their status as the largest opposition party gives them their biggest platform yet.

But the AfD’s rise has also seen a change in tone from Mrs Merkel – in her first major speech of her new term she said that the “humanitarian exception” of 2015 would not been repeated, as well as promising to beef up border security and boost deportations.

Austria

A far-right party in neighbouring Austria has enjoyed even greater success than the AfD.

Last year saw the Freedom Party (FPÖ) become junior partner in a coalition with the government of Conservative Chancellor Sebastian Kurz. The Conservatives along with the centre-left Social Democrats have long dominated Austrian politics.

The FPÖ had already only narrowly lost a presidential election in which the two main centrist parties did not even make the second round.

As in Germany, the migrant crisis is also seen as key to their success, and an issue they long campaigned on.

Mr Kurz has vowed a hard-line on immigration; during the campaign the FPÖ even accused him of stealing their policies.

Since the election there have been proposals to ban headscarves for girls aged under 10 in schools and plans to seize migrants’ phones.

Sweden

The anti-immigration Sweden Democrats (SD) made significant gains in the 2018 general election.

They won about 18% of the vote, up from 12.9% last time.

The party has its roots in neo-Nazism, but it rebranded itself in recent years and first entered parliament in 2010.

Meanwhile, the centre-left Social Democrat party of Prime Minister Stefan Lofven has seen support ebb away.

The Social Democrats are a party associated with generous social welfare and tolerance of minorities, while the SD opposes multiculturalism and wants strict immigration controls.

Like many of the countries featured here, though, the picture is complex. Sweden has welcomed more asylum seekers per capita than any other European country and has one of the most positive attitudes towards migrants.

France

Despite the efforts of leader Marine Le Pen to make the far-right National Front palatable to France’s mainstream, she was comprehensively defeated by Emmanuel Macron for the presidency in May 2017.

Marine Le Pen is anti-EU, opposed to the euro and blames Brussels for mass immigration.

In 2010 she told FN supporters that the sight of Muslims praying in the street was similar to the Nazi occupation in World War Two.

Since their loss in the presidential election, the FN suffered an underwhelming result in parliamentary elections, winning a small handful of seats while Mr Macron’s party dominated.

More recently the party has renamed itself as the National Rally, with Ms Le Pen saying she would seek to gain power through forming coalitions with allies.

Hungary

In April, Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban secured a third term in office with a landslide victory in an election dominated by immigration.

The victory, he said, gave Hungarians “the opportunity to defend themselves and to defend Hungary”.

Mr Orban has long presented himself as the defender of Hungary and Europe against Muslim migrants, once warning of the threat of “a Europe with a mixed population and no sense of identity”, comments that led to him being called a racist.

He is arguably the leading voice among the Visegrad countries in Central Europe – Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia – that oppose EU plans to compel countries to accept migrants under a quota system.

Slovenia

Although it fell a long way short of a majority, the anti-immigrant Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS) was the largest party in this year’s general election.

The party is led by former Prime Minister Janez Jansa, who like the Visegrad leaders opposes migrant quotas, and has said he wants Slovenia to “become a country that will put the wellbeing and security of Slovenians first”.

During the campaign he formed an alliance with Mr Orban, borrowing his tactic of stirring fears about migrants.

Slovenia, though, only accepted 150 asylum applications last year. During the migrant crisis most of those on the move used the Balkans and Central Europe as transit towards the West.

Poland

Another party that has condemned the EU’s handling of the migrant crisis, the conservative Law and Justice party secured a strong win in 2015 elections.

Some of the party’s most high-profile policies, such as taking control of state media and judicial reforms that allow the government to sack and appoint judges, have alarmed the EU.

Law and Justice was also behind a controversial law making it illegal to accuse the Polish nation or state of complicity in the Nazi Holocaust, which some saw as an attempt to whitewash the role of some individuals in Nazi atrocities.

Poland and Hungary have offered each other political support, such as over migrant quotas and Viktor Orban expressing “solidarity” with Poland in its battle over court reforms.

Elsewhere in Europe…

Source: Read Full Article