Home » Latin America »

What’s behind Venezuela’s political crisis?

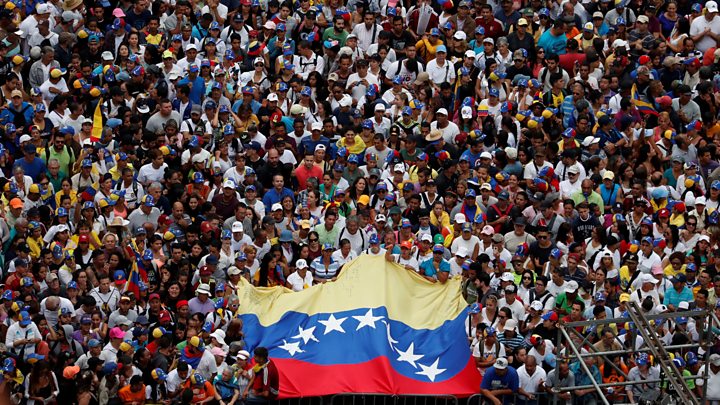

Venezuela’s political crisis appears to be reaching boiling point amid growing efforts by the opposition to unseat the socialist president, Nicolás Maduro.

The South American country has been caught in a downward spiral for years with growing political discontent further fuelled by skyrocketing hyperinflation, power cuts and shortages of food and medicine.

More than three million Venezuelans have left the country in recent years.

But what exactly is behind the crisis rocking Venezuela?

Who’s the president?

This would be an unusual question to ask in most countries, but in Venezuela many want to know exactly that following the dramatic events of 23 January.

On that day, the leader of the legislature, Juan Guaidó, declared himself acting president and said he would assume the powers of the executive branch from there onwards.

The move was a direct challenge to the power of President Nicolás Maduro, who had been sworn in to a second six-year term in office just two weeks previously.

Not surprisingly, President Maduro did not take kindly to his rival’s move, which he condemned as a ploy by the US to oust him.

He also said that he was the constitutional president and would remain so.

Why is the presidency disputed?

Nicolás Maduro was first elected in April 2013 after the death of his socialist mentor and predecessor in office, Hugo Chávez. At the time, he won by a thin margin of 1.6 percentage points.

During his first term in office, the economy went into freefall and many Venezuelans blame him and his socialist government for the country’s decline.

Mr Maduro was re-elected to a second six-year term in highly controversial elections in May 2018, which most opposition parties boycotted.

Many opposition candidates had been barred from running while others had been jailed or had fled the country for fear of being imprisoned and the opposition parties argued that the poll would be neither free nor fair.

Mr Maduro’s re-election was not recognised by Venezuela’s opposition-controlled National Assembly.

Why is it all coming to a head now?

After being re-elected to a second term in early elections in May 2018, Mr Maduro announced he would serve out his remaining first term and only then be sworn in for a second term on 10 January.

It was following his swearing-in ceremony that the opposition to his government was given a fresh boost. The National Assembly argues that because the election was not fair, Mr Maduro is a “usurper” and the presidency is vacant.

This is a line that is being pushed in particular by the new president of the National Assembly, 35-year-old Juan Guaidó.

Citing articles 233 and 333 of Venezuela’s constitution, the legislature says that in such cases, the head of the National Assembly takes over as acting president.

That is why Mr Guaidó declared himself acting president on 23 January.

What has the reaction been?

US President Donald Trump officially recognised Juan Guaidó as the legitimate president of Venezuela just minutes after the latter had said he would take over the executive powers.

The citizens of Venezuela have suffered for too long at the hands of the illegitimate Maduro regime. Today, I have officially recognized the President of the Venezuelan National Assembly, Juan Guaido, as the Interim President of Venezuela. https://t.co/WItWPiG9jK

End of Twitter post by @realDonaldTrump

Predictably, this met with a swift response from Nicolás Maduro, who has long said that the US is behind attempts to drive him from office.

Mr Maduro broke off relations with the US and gave US diplomats 72 hours to leave Venezuela.

Within Venezuela, those opposed to the government celebrated Mr Guaidó’s move, while government officials said they would defend the president from “imperialist threats”.

What next?

Juan Guaidó called on all of those opposed to President Maduro and his government to continue protesting “until Venezuela is liberated”.

While Mr Guaidó counts with the support of the US, a number of Latin American countries and other international leaders, he does not have much power in practical terms.

He is the president of the National Assembly, but this legislative body was largely rendered powerless by the creation of the National Constituent Assembly in 2017, which is exclusively made up of government-loyalists.

The opposition-controlled National Assembly has continued to meet, but its decisions have been ignored by President Maduro in favour of those made by the National Constituent Assembly.

Who can break the impasse?

The security forces are seen as the key player in this crisis. So far, they have been loyal to Mr Maduro, who has rewarded them with frequent pay rises and put high-ranking military men in control of key posts and industries.

Following the events of 23 January, top military commanders tweeted their support for Mr Maduro but videos posted on social media showed National Guard members stepping aside at one opposition protest to let those marching through.

Mr Guaidó has promised all security forces personnel an amnesty if they break with President Maduro.

How did Venezuela get this bad?

Some of the problems go back a long time. However, it is President Maduro and his predecessor, the late President Hugo Chávez, who find themselves the target of much of the current anger.

Their socialist governments have been in power since 1999, taking over the country at a time when Venezuela had huge inequality.

But the socialist polices brought in which aimed to help the poor backfired. Take price controls, for example. They were introduced by President Chávez to make basic goods more affordable to the poor by capping the price of flour, cooking oil and toiletries.

But this meant that the few Venezuelan businesses producing these items no longer found it profitable to make them.

Critics also blame the foreign currency controls brought in by President Chávez in 2003 for a flourishing black market in dollars.

Since then, Venezuelans wanting to exchange bolivars for dollars have had to apply to a government-run currency agency. Only those deemed to have valid reasons to buy dollars, for example to import goods, have been allowed to change their bolivars at a fixed rate set by the government.

With many Venezuelans unable to freely buy dollars, they turned to the black market.

What are the biggest challenges?

Arguably the biggest problem facing Venezuelans in their day-to-day lives is hyperinflation. The annual inflation rate reached 1,300,000% in the 12 months to November 2018, according to a study by the opposition-controlled National Assembly.

By the end of 2018, prices were doubling every 19 days on average. This has left many Venezuelans struggling to afford basic items such as food and toiletries.

The price of a cup of coffee in the capital Caracas doubled to 400 bolivars ($0.62; £0.50) in the space of just a week last December, according to Bloomberg.

What’s the government doing about it?

Back in August, the government lopped five zeros off the old “strong bolivar” currency and gave it a new name – the “sovereign bolivar”. This meant people no longer had to carry such huge amounts of cash.

It also began circulating eight new banknotes worth 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 sovereign bolivars and two new coins.

The new currency is part of an “economic package” of measures which the government says is the “magic formula” to help Venezuela’s battered economy recover.

Among the measures were:

However, the currency has continued to fall since its introduction, and a further minimum wage increase has had to be introduced, leading to questions over how effective the move was.

How have Venezuelans reacted?

Many people have been voting with their feet and leaving Venezuela. According to United Nations figures, three million Venezuelans have left the country since 2014 when the economic crisis started to bite.

However, Vice-President Delcy Rodríguez has disputed the figures, saying they are inflated by “enemy countries” trying to justify a military intervention.

The majority of those leaving have crossed into neighbouring Colombia, from where some move on to Ecuador, Peru and Chile. Others have gone south to Brazil.

The mass migration is one of the largest forced displacements in the western hemisphere.

Source: Read Full Article