Home » Latin America »

Reviving Colombia’s ‘language of resistance’

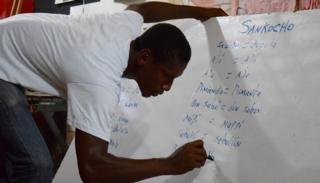

Gustavo Reyes Reyes stands in his language class in front of two dozen energetic children who have been tasked with calling out the names of the ingredients found in “sancocho”, a Colombian stew.

“Apù!” the students shout out together, which means water in the town’s native language, Palenquero.

Palenquero is one of the 68 languages found in Colombia and is a mix of Spanish and African Bantu languages. But with just a few thousand speakers, it has not been easy to keep the language alive.

Now residents of San Basilio de Palenque like Mr Reyes want to ensure the language that has defined their culture does not die out.

“One of the most important aspects of [Palenque] is the Palenquero language,” said Mr Reyes, who works for the ethno-education NGO Tiela Ri Pá.

“In a way, it’s something we brought from Africa.”

First free town in the Americas

The small, sweltering town 50km (30 miles) from the Caribbean coast is perhaps most renowned for Palenqueras, women in colourful dresses who walk the streets of the touristic colonial city of Cartagena, selling sweets and fruit.

But Palenque has another legacy. It is the first free town in the Americas.

You may also be interested in:

It was founded in 1603 by Benkos Biohó, who escaped slavery in the late 16th Century and led a rebellion to help others escape to the foothills of the mountains surrounding Palenque.

According to linguist Rutsely Simarra Obeso, more than 70 African languages were once spoken in Cartagena, which was a gateway to the slave trade.

Black men and women from different ethnic groups who had escaped slavery created Palenquero, a creole language, to communicate with each other.

“With the language began an exercise of resistance,” she says. “When you don’t allow your language to disappear, future generations are going to have information about the elements that define your cultural identity, your ethnic identity.”

And this is something that rings true for residents in Palenque today.

With upwards of 3,500 inhabitants, the town is recognised by Unesco on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity for maintaining social, religious, musical and traditional medical practices - which have African roots - as well as the Palenquero language.

Loss of language

But the language has slowly slipped away from the culture that created it: now more people speak Spanish than Palenquero in the town.

According to the most recent 2009 Colombian government data, only 18% of people were fluent in it and just 21% of Palenquero speakers were under the age of 29.

Andris Padilla Julio says part of that is due to residents facing discrimination for speaking their native language.

He is the leader of the rap group Kombilesa Mi, which performs in Palenquero and organises free language, traditional music and dance workshops for children in the town.

“When people hear Palenqueros speaking, to them it [appears] a poorly spoken Spanish because they don’t understand it. But that’s wrong. And because of that, many people stopped speaking Palenquero when they left,” he says.

“A father or mother would say ‘don’t speak the language so they don’t make fun of you, so they don’t laugh at you’.”

However since the 1980s, there has been a push by Palenque residents to recognise the value of their cultural traditions through ethno-education.

The Palenquero language began to be taught in the local school, named after Benkos Biohó, in the 1990s and today it is protected under Colombia’s 2010 Native Language Law.

Because of efforts like these, Ms Simarra estimates that now 20% to 25% of Palenqueros speak the language well.

A language of resistance

In Palenque, a tall, bronze statue of Benkos Biohó breaking out of chains overlooks the principal square.

There are also murals commemorating the founder painted around the town, as well as ones depicting the drums which feature heavily in the town’s annual percussion festival.

“Now people are more conscious about what it means to be from Palenque,” says language teacher Bernardino Pérez Miranda.

And for him, Palenquero is still a language of resistance. “When I go out I’m always speaking Palenquero, in Bogotá, in Cartagena, here and in front of white people,” he says.

“It’s a way to show others that our language has the same value.”

At a Kombilesa Mi workshop, 50 or so kids are in a train formation, holding on to each other’s shoulders as they move through the streets of Palenque.

They are dancing to the thud of traditional percussion instruments and mix the two languages, Spanish and Palenquero, as they sing.

“They are the present but they’re also the future,” says Mr Padilla. “The idea is to always move forward with the tradition of San Basilio de Palenque, so it is never lost.”

You may also like to watch:

Source: Read Full Article