Home » Latin America »

Farewell to ‘a titan of the free press’

When plainclothes policemen came to the Buenos Aires Herald’s office brandishing machine guns, the newspaper’s staff knew they were coming.

It was 22 October 1975 and the police were looking for the small Argentine newspaper’s news editor, Andrew Graham-Yooll.

A visit from armed police would normally have meant certain death, but the office had been tipped off in advance, and someone had already been able to get word out to a lawyer and to overseas news agencies, meaning the raid was on the record.

The staff kept calm and let the men in leather jackets storm around the office, waving their weapons around and making a show of destroying Graham-Yooll’s files from 10 years in the job. He was in their sights because he had attended press conferences for a guerrilla group. This made him a terrorist suspect, they said.

At the time, the military was tightening its grip on the country and was months away from claiming power in a coup. Anyone considered remotely subversive was being “disappeared” – kidnapped and then jailed or murdered.

Graham-Yooll was briefly whisked away in an unmarked car with his editor, Robert Cox, who had insisted on accompanying him. The pair later recalled how they were taken to a police department and held in a cell, where music from a full-volume radio could not block out the sounds of people screaming as they were tortured in the basement.

Eventually, they were both allowed to leave.

That same week, the Buenos Aires Herald’s small team did what it always did during that period. It refused to be intimidated into silence and told its readers what had happened, with a satirical column entitled “Wot, no tanks?”

Cox and Graham-Yooll went back to their desks. They had an enormous job to do. People were disappearing across the country and their newspaper was the only outlet in the country consistently reporting on it.

When Andrew Graham-Yooll died suddenly in London on 6 July, aged 75, Argentina mourned.

“It is not often when a journalist dies here that their death is on the front page across all major news sites,” says James Grainger, editor of the BA Times, a new publication where Graham-Yooll had recently been a columnist. “He was a titan.”

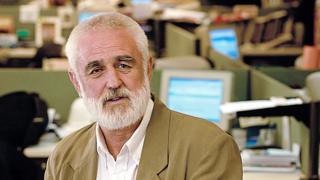

Years earlier, an Argentine news magazine had chosen him as its cover star, dubbing him “one of the bravest journalists of the 1970s”. The photograph shows him stroking his white beard and pointing an accusatory finger at the camera. In reality, he was far less intimidating, with a husky laugh and a humble view of his legacy.

A prolific reporter, historian and poet, he went on to write numerous books, including A State of Fear (1985), which is considered one of the most valuable accounts of the dictatorship.

Yet Andrew was best known for his time at the Buenos Aires Herald, which as a small-circulation newspaper published in English in a Spanish-speaking country, became an unlikely major player in Argentine history.

Six months after that office raid, a military coup led to a systematic reign of terror, which lasted until the end of 1983. An estimated 30,000 people died, as the authorities moved from targeting left-wing guerrillas, students and trade unionists, to psychologists, artists and journalists, and their friends and families.

Four weeks after the coup, the Buenos Aires Herald received a phone call. The voice at the other end said all media was henceforth banned from reporting on any deaths or disappearances, unless they had been confirmed by authorities.

The newspaper, once again, tackled the issue head-on and published a story about the warning. Soon it gained a reputation. People started turning up at its office, having been turned away by other outlets, asking for help finding missing loved ones.

One of Graham-Yooll’s biggest assets was his local contacts book. Born in Buenos Aires, to an English mother and Scottish father, he was also perfectly bilingual. When he spoke Spanish, he had his hometown’s distinctive Italian-influenced Porteño accent; when he spoke English, there was a slight and very gentle Scots lilt.

He was also very sociable and loved a drink. In later years, he admitted to friends that he often put work first and neglected his family.

“You couldn’t tell Andrew what to do,” says Cox, his former boss and longtime friend. “Sometimes I didn’t know what he was up to and that was probably for the best. He would go off, like in a spy movie, with a newspaper under his arm [as a signal], going from cafe to cafe to meet people.”

Cox had also regularly tried to persuade him not to go a weekly lunch with certain Argentine journalists, as the industry had been infiltrated by members of the military. “It was horrible thing, full of old monsters and likely to put him in even more danger, but he would go and get roaring drunk,” recalls Cox.

And he would often come back with stories. On one occasion, in May 1976, he found out that the home of renowned playwright and novelist Haroldo Conti had been raided and he had disappeared.

Graham-Yooll later said: “I had friends of Conti telling me I had to publish and there was a naval officer there too, who said ‘Don’t you dare, you know what will happen to you’.”

Though he did not comment either way at the time, he wrote the story as soon as he was back at his desk, having been encouraged and backed by Cox. Graham-Yooll said he was terrified while sending that edition to press. In the years afterwards, he always resisted being cast as the fearless hero.

Later in 1976, Graham-Yooll was forced into exile. A contact had told him he was about to be targeted again, and this time they would not let him go. It was said that his wife was also on the hit list – simply because she had gone to university with Che Guevara’s sister. Cox was also later forced into exile, after death threats were sent to his son.

Graham-Yooll used his dual nationality to move his family to the UK, where he found work at the Daily Telegraph and the Guardian, before moving to another small operation, the free-speech organisation Index on Censorship.

Read about other notable lives

For years, while still living in Argentina, he had been secretly feeding information to Index on Censorship, as well as Amnesty International. He knew that letters addressed to human rights groups would be intercepted, so he covered his tracks by sending the information to them via a friend at the Daily Telegraph in London. Cox says he did not know this at the time. “If anyone found out, that was a certain death sentence.”

In London, Graham-Yooll became Index on Censorship magazine’s editor. I worked for the same magazine years later, and it was while tracing its history that I got to know Graham-Yooll.

The publication had been founded in 1972, with an eye mostly on Eastern Europe. His successor, Judith Vidal-Hall, says: “Andrew was absolutely instrumental in broadening the understanding of censorship as going far beyond the idea of it being led by wicked Communists. It was a universal phenomenon in a way no-one had anticipated.”

She also remembers a key incident from circa 1984, when he was summoned back to Argentina as a key witness in post-dictatorship trials.

Before he left London, he gave Vidal-Hall a package of papers, instructing her to keep it safe and implying he may not make it back alive. Many of the murderers and torturers were still walking the streets. “To this day, I don’t know why I did this,” she says of the stout brown envelope, “but I put it under my mattress. I never opened it and I didn’t have a clue what was inside.”

After he returned safely, he opened the package in front of her. Inside was an array of handwritten notes and lists – names, places, dates – about all the people who he knew had disappeared in Argentina. It was a crucial piece of history that had slipped through the censors’ net.

Graham-Yooll had also kept a tally of Argentina’s crimes via the back pages of Index on Censorship’s magazine. In those days, it contained a country-by-country directory, which briefly listed free-speech violations around the world as a matter of record.

A few years ago, I started exploring those archives. When you piece together the Argentina entries, it is a rare, almost real-time record of atrocities, collectively spanning 14,000 words and hundreds of individual stories.

One of them – just a paragraph long – briefly referenced linguist Cristina Whitecross and her publishing-industry husband Richard, who were being held in the notorious Villa Devoto prison in Buenos Aires.

The couple were eventually released and went on to build a new life in Oxfordshire, England. Like many others, they were grateful to Andrew and others, who had ensured they were not forgotten. The simple act of publishing and circulating names let the military know that someone was watching, and could make all the difference.

“Richard and I often felt we owed our lives to him,” she says today of her “great friend Andrew”.

After 18 years in exile, Graham-Yooll moved back to Buenos Aires, where he was particularly revered by the Anglo-Argentine community, and became editor of the Buenos Aires Herald.

More recently, he had been living a quieter life in a sleepy town in Entre Rios province, further north.

Judith Vidal-Hall says she remembers asking him why took the risks he did. In his typically low-key manner, he said he was just doing his job – reporting on what was going on his country.

“Of course we were afraid,” he once said, according to the BA Times. “But it’s one thing to be afraid, and another thing to be a coward.”

More lives in profile

Source: Read Full Article