Home » Latin America »

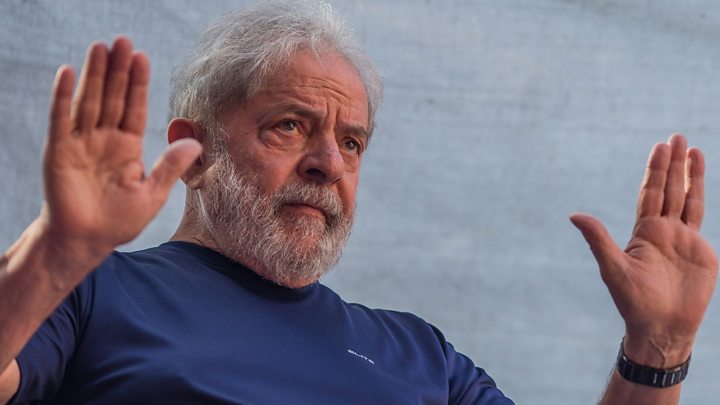

Brazil’s Lula: Saint or sinner?

Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva is seen as much as a saviour as he is a sinner in Brazil: a man who came to power promising change yet ended up leaving politics with a very different legacy.

His life mirrored that of many Brazilians. He was born in 1945 into a poor family in the north-east of Brazil and, by the time he was seven, his family had moved to São Paulo to find work – as many millions of Brazilians have done, before and after him.

Lula did not learn to read until he was 10. At the age of 14, he got his first job as a metal worker in the car factories on the outskirts of São Paulo.

It was in those factories that he started getting involved in politics. By 1975, he was heading the metalworkers’ union and, throughout the 1970s and 80s, he helped organise major strikes in defiance of Brazil’s military rule.

“The working class has never got anything in this world without a battle, without perseverance and without the will to fight until the end,” he told workers in April 1980.

In the same month, he was arrested for his involvement in the strikes and held in prison for a month.

Founding the Workers’ Party

Shortly after his release he helped found the Workers’ Party, the first major socialist party in Brazil’s history. The party brought together trade unionists, intellectuals and activists who were set on changing Brazil’s power structure.

But it was a long struggle to the top. Lula ran for president unsuccessfully three times before eventually being elected in 2002.

And when he was, he made history as Brazil’s first working-class president, who argued it was time for Brazil to turn a new page.

“Change: that was the key word, that was the message from Brazilian society,” he said as he was sworn in, in January 2003. “Society decided it was time to forge a new path.”

He led Brazil during a period of unprecedented economic growth. High prices for commodities meant that he had money to spend on social programmes.

One of his biggest legacies was lifting millions out of poverty, according to his former foreign minister, Celso Amorim.

“Taking 30 to 40 million people out of poverty is fantastic,” says Mr Amorim.

“They [Brazilians] identify with Lula because he’s one of them, coming from poorer parts, then becoming a metal worker, and then all the way to the presidency, without departing from these origins.”

Spendthrift

But he also faced criticism for spending money without addressing the core problems in society.

“Everyone was happy because everyone had access to credit,” argues political analyst Thiago de Arago. “This is a mechanism that didn’t come from the brilliance of an economic plan but from the circumstance of the moment.”

The good times could not last forever. After serving two consecutive terms in office, the maximum allowed under Brazil’s constitution, Lula stood down on 1 January 2011.

His ally Dilma Rousseff succeeded him as president but as economic growth slowed, political dissatisfaction grew.

In 2013, protests that started over a rise in bus fares grew into a widespread expression of anger with corrupt politicians, a situation that intensified with the start of Operation Car Wash in 2014, the biggest corruption investigation the country has ever seen.

Lula was a man who said he would represent change, but in the end, he too was charged with corruption.

‘You can’t arrest my ideas’

In 2017 he was sentenced to nearly a decade in prison over allegations he accepted a beachfront apartment in return for political favours from a construction company.

In 2018, his sentence was extended to 12 years.

It is a charge that has divided Brazil between those who feel that he and his Workers’ Party have been unfairly treated and those who believe justice has been served.

Lula’s legacy is mixed. “It proved that in a country like Brazil today, he cannot be protected just because of how big he was,” says Mr Arago. “I think this is a major legacy that Lula will leave for Brazilians: that no one is above the law.”

For months, he fought to remain out of jail, but in April the Supreme Court said he had to start serving time.

From the metalworkers’ union where he began his career, he gave his last speech: “There is no point in trying to end my ideas, they are already lingering in the air and you can’t arrest them. There is no point in trying to stop me from dreaming, because once I cease dreaming, I’ll keep dreaming through your minds and your dreams.”

“They have to know that the death of a fighter cannot stop the revolution,” he said to the crowd.

And even behind bars Lula has kept up the fight. But it is one he has finally lost and which has led to the fall from grace for the man who was once Brazil’s most popular politician.

He is out of politics now but still in the minds of many and will continue to be formidable influence in Brazilian politics for a while to come.

Source: Read Full Article