The human rights of more than 500 people may have been breached in COVID-related ‘do not resuscitate’ decisions, a shock report claims

More than 500 people may have had their human rights breached over ‘do not resuscitate’ decisions made during the coronavirus pandemic, it has been revealed.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) has called for ministerial action to tackle the “worrying variation” in people’s experiences of ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ (DNACPR) decisions.

Some families, it says, were not properly involved and others totally unaware decisions had been made.

A combination of “unprecedented pressure” on providers and “rapidly developing guidance” may have led to situations where DNACPR decisions were incorrectly conflated with other clinical assessments, the care regulator has claimed.

The CQC was asked by the Department of Health and Social Care to conduct a rapid review of how DNACPR decisions were used at the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

It followed concerns decisions were being made without the involvement of patients or relatives, and that they were being applied in a blanket way to particular groups, for example people with learning disabilities.

And the CQC’s interim report in December found doctors may have made blanket decisions without the input of patients or their families during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now, the regulator is calling for a Ministerial Oversight Group to work with health and care providers, local government and the voluntary sector to deliver improvements.

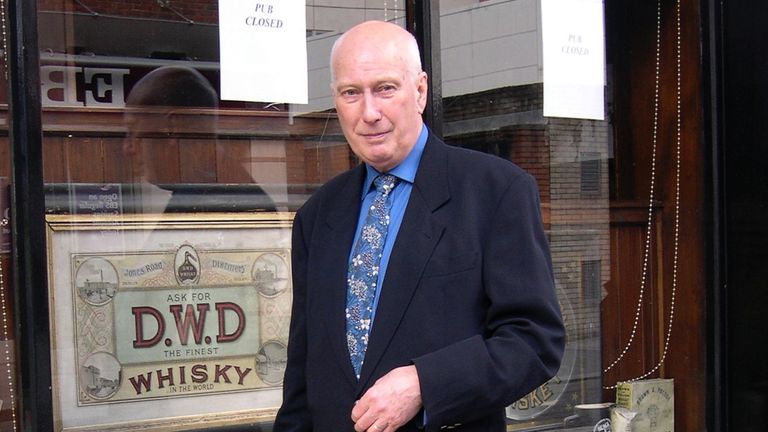

Here, Marcelle Bernstein talks about the day her husband Eric was ‘deprived of his dignity’

“My husband was a brave and obstinate man: despite numerous medical problems (two heart attacks, open heart surgery, two strokes, an aneurysm and prostate cancer) and taking an array of drugs, he kept working and travelling to do so.

“Writers can’t afford to stop and wouldn’t want to anyway.

“At 76, he was writing for the Telegraph Magazine, and flying with London’s air ambulance rescue helicopters from the top of the Royal Free Hospital. (He said if he had a heart attack climbing endless stairs to the roof launch pad, he was with the right people.)

“Two years ago at 81, a chest infection took him into a major London hospital.

“He had always told every doctor who even glanced at him that when he died, he didn’t want to be revived: his nightmare was being brought back to find himself incapable in some way.

“At the time I was certain a DNR decision (formally called a Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) must have been recorded in his notes – somewhere – but later when I requested them, I could see no record.

“And there were no signs above his bed detailing this instruction, though what did I expect? A black finger pointing up? Or down? But I was anyway convinced that if things got serious, I would be at his side to reinforce his wishes.

“In the event, to my endless regret, I wasn’t.

“He spent a week in the high dependency unit, then caught some hospital bug.

“He was in various wards for another month, home for ten days, then was readmitted one Saturday morning.

“I should have worried more, only it had all become weirdly normalised.

“Forty-eight hours later, just before dawn, he was found ‘unresponsive.’

“I was there in 20 minutes to find the crash team already hard at work: A terrible thumping – an almost industrial sound – was incongruous behind the blue bed curtains.

“I screamed ‘Stop, stop!’

“He didn’t want it.

“They should have known his wishes.

“He deserved dignity – but was deprived of it.

“They apologised profusely later, but the noise of that machine pounding away, pummelling his chest, was deeply upsetting – and unforgettable.

“I don’t know if his DNR was not properly recorded, or simply not communicated, but it’s clear that improvements need to be made if people’s last wishes are to be honoured.”

Source: Read Full Article