The French village that fears for its Brits

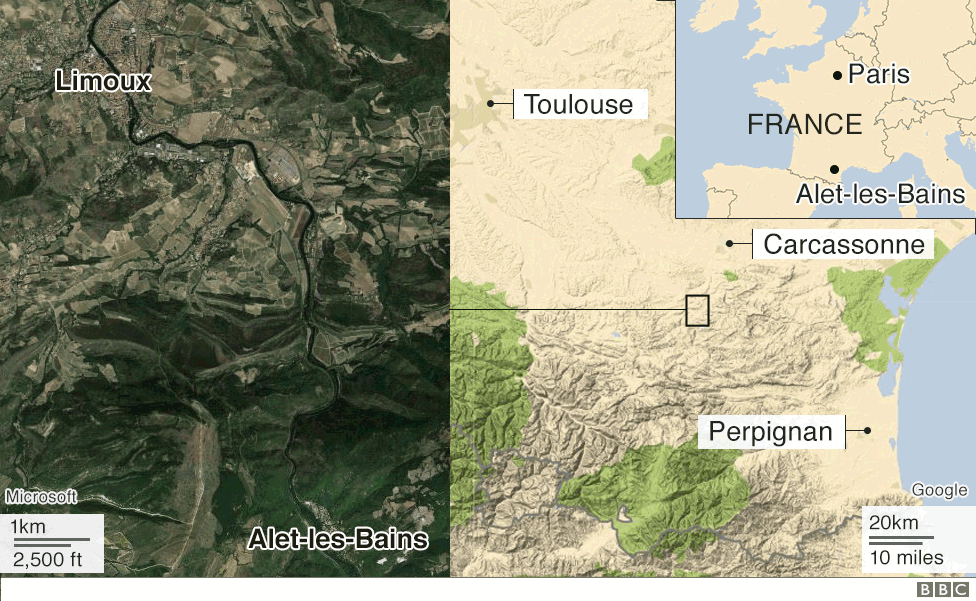

Alet-les-Bains in southern France may be a long way away from the UK, but Brexit looms large there.

And it’s not just the large number of Britons among its 440 residents who worry about the future.

“Our English friends have done a lot for the village,” says resident Annick Van Mairis. “Thanks to them, dilapidated houses have become beautiful. Our main fear is that they should have to leave for some reason or other.”

In a country not renowned for being Anglophile, the warm feelings towards Alet’s 60-strong British community are striking. Retired postman Gérard Baudru says they have brought “brotherhood” to the village – as well as work for himself. “The number of greeting cards in in December and January is extremely high,” he enthuses.

The mutual attraction between Alet and its British residents is rooted in geography. The village is located in Aude, the second-poorest area in mainland France. It has no industry.

Its main city, Carcassonne, has half the population of Oldham in the north-west of England and five times its unemployment rate (24% to Oldham’s 4.5%).

Aude may be struggling economically but, attracted by the stunning scenery, the lifestyle and dirt-cheap property prices, pensioners started trickling in from Britain and other parts of northern Europe in the 1980s.

When Ryanair began operating flights from London and Manchester to Carcassonne in 1998, the trickle became a flood.

English not spoken

Alet, a medieval spa town with a Ninth-Century abbey, caught the eye of many. One of the early arrivals, Min Stevenson, had originally planned to settle with her husband in a country house near the Pyrenees but decided on Alet instead.

“We thought, if we do that we won’t feel as if we’re living in France,” she recalls. “What I want is to be in a village. And I like the fact that people come along and say ‘Hello, nice to see you’. The French people were very friendly.”

Their story is typical. British expats in Aude seek to blend in with the local culture rather than set up their own enclave.

When David Goldsworthy settled in Limoux, a medium-sized town a 10-minute drive from Alet, fellow Brits were the last people he wanted to run into.

“When I heard English voices at the supermarket or Mr. Bricolage [hardware store] I went the other way. I wasn’t here for that. I was here to try to become part of the landscape.”

L’Odalisque, a Limoux restaurant, has been popular with Britons since it opened three years ago. They make up 50% of its patrons even though owner Sven Choplin does not speak a word of English. “We tried to translate our menu at first. The English said: ‘stop! This is meaningless. We’d rather make the effort.'” he laughs.

Annie Morejon – who owns the only store in the village, a grocery shop-cum-café – finds that some even out-French the French. Unlike the natives, who “are sometimes not very polite, they come and give me a kiss”, she says.

Grand designs

Far from recreating Little Britain, the newcomers are busy rebuilding old France.

Until the arrival of the British and others, traditional homes in villages like Alet were crumbling. “People from Aude did not value their own heritage,” says Catherine Pouedras, who works at the Carcassonne tourist office.

The newcomers eagerly bought properties to do them up. They have done so “in a way that respects the tradition and the harmony of the village,” Alet Mayor Ghislaine Tafforeau says.

This renovation work has been “a lesson for natives”, who she says are mainly interested in building identikit modern villas with gardens on the outskirts. One of the prettiest streets in the centre of the village, the mayor points out, is known locally as “la rue des Anglais”.

The British, says Alet resident Martine Théveniaut, “have breathed new life into the place”.

You will, if you try hard, find people in Alet who take exception to the British influx. Standing in a square, builders grumble about being undercut by a foreign workforce.

“The English give work to each other,” one says. Another blames EU rules that allow “posted workers” to escape France’s high social security contributions.

But both men agree that if it were not for the British, half the houses in a nearby town would still be derelict.

In the run-up to Brexit, however, fewer people have been snapping up such properties.

Christophe Bac, a Limoux estate agent who advertises extensively in the UK, says the fall in the pound has meant that his share of British buyers has dropped from 30% a few years ago to 15% now.

Some who find it increasingly difficult to make ends meet are already selling up, Mr Bac adds.

‘Anglet-les-Bains’

Beyond the property market, Brexit could have consequences for the community life of villages like Alet.

The most crucial British investment there has not been in stone and mortar, but in time and effort. The expats have brought to Alet an Anglo-Saxon zeal for self-help and grassroots action.

The local British brigade plays a leading role in every charity sale and village fair. They staff a workshop that makes the Alet coat of arms displayed at festivities.

They have raised funds to put flowers around the village ever since the municipality’s budget ran out a few years go.

The Brits organise quiz nights and poetry evenings. One hosts a film club that screens alternately French and English-language films (with subtitles for each) every month.

Alison Hope settled in Alet in 2013, and bought part of a 200-year-old former nougat factory from another Briton.

She is making Robin Hood costumes for the Christmas pantomime – a British tradition the expats have introduced to Alet. “French people do go,” she says. “This year we’re putting up signs with subtitles so they can follow the action.”

“Whenever we ask for help to set up an event, the English-speaking community is always there,” says Jozy Laval, who heads Anim’Alet, a volunteer group. “I like to say that this place is not Alet-les-Bains, but Anglet-les-Bains.”

Deputy Mayor Jean-Pierre Gayda agrees that without them the village would have no civic life to speak of.

“I’m happy that the English are here in Alet – except during the 80 minutes of Le Crunch,” he jokes, drawing the line at France against England at rugby.

Staying on?

Dawn Stollar settled in the village back in the 1980s after falling “in love with the region”. Now a sprightly 80, she remains a leading force in Alet’s civic life.

A few years ago she drew up a list of emergency numbers and volunteers that sick people could call when they needed help, or have a meal brought to their home. The list was particularly useful when the Aude valley was devastated by floods in mid-October, when the equivalent of five months of rain fell in a few hours.

But it is unclear how much longer Alet will benefit from Dawn’s energy. She is deeply worried she will be forced to return because of Brexit.

One major source of concern for retired expats like her is health coverage. Although they would continue to have access to medical care under the Brexit withdrawal deal, the future is far from certain.

And then there is money. Those living on pensions in sterling have already seen a 20% fall in their income since 2016. “There’s a limit to how much the elastic can stretch,” Dawn says.

“I lie in bed thinking: What happens if I’m left alone and the income drops so much? What do I do? You obviously go back to your children. That would be fun wouldn’t it? Grannies from all over France and Spain trooping back to England to be with their children.”

“All my life I got through everything somehow or other. But this one is coming very late in one’s life, and you thought of nice old age in a beautiful place, and suddenly there is this tension.”

Knock-on effects

Brexit is also bad news for the local economy. As their incomes dwindle, expats are spending less.

The Britons’ legendary enthusiasm for do-it-yourself has meant brisk business over the years for Mr. Bricolage in Limoux.

If Brexit drives many away, says store manager Gaëtan-Pierre Dumonceau, “this would have a negative impact on our sales, and also on the villages where they are so heavily invested.”

The travel industry, the Aude’s main cash earner, is already feeling the pinch. The British are its main foreign customers and the number of those visiting camp sites in the area was down 27% between 2015 and 2017.

In other words, many Britons looking for value holidays – the kind of tourism Aude specialises in – are staying away.

Antoinette Fairhurst, who runs a Bed and Breakfast in Alet with a husband, notes that her income from the past summer’s high season plummeted by two-thirds compared with last year. “I hardly had any English that came,” she says.

François Raynaud of the regional tourism agency fears Brexit could make things worse, with tougher border checks. “If the British don’t come to Carcassonne that will leave a big hole,” he says.

Aude’s other money spinner is wine. The blanquette de Limoux, a bubbly that locals compare favourably to champagne, is sold worldwide, with the British among the keenest drinkers.

Le Sieur d’Arques, Limoux’ leading winemaker, sells to UK supermarket chains such as Tesco and Waitrose.

Brexit could hit sales with extra taxes and paperwork, says Sieur d’Arques export manager Gabi van Dael. “We are very worried about what is going to happen next year.”

Françoise Antech-Gazeau is head of Antech, an old Limoux family-run firm that specialises in high-end sparkling wine.

Her main concern is not about the extra bureaucracy after Brexit – Antech has done business with generations of keen British customers and “we will always find solutions”.

But she fears a Brexit-induced downturn that could hit the purse of the British and lead them to drink less blanquette.

Brexit will not end the love affair between the British and Aude. The many who have moved there to work are determined to stay, and are busy getting residency permits or French citizenship.

“In terms of Brexit, you would have to shoehorn me out with a shotgun,” says Charlotte Pye, a yoga teacher who helps kids in rugby clubs up and down the Aude valley in her spare time. “My life is here.”

But in an area with an economy on the brink, any drop in foreign income can make a big difference. And in a tiny place like Alet, the departure of even a few of its most active residents poses a threat to community life.

“Brexit is a danger for us,” says Anim’Alet volunteer Claude Carayol. “If the British are not there, who will replace them?”

Photographs by Samuel Aranda/Panos Pictures

Source: Read Full Article