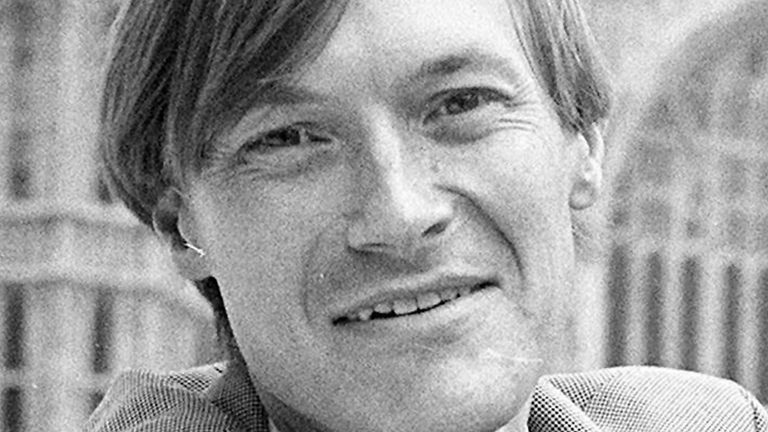

Prevent: Why key part of government’s counter-terrorism strategy is under scrutiny after murder of MP Sir David Amess

A key part of the government’s counter-terror strategy has returned to the headlines in the wake of the killing of MP Sir David Amess.

A Whitehall source has told Sky News that the suspect in Sir David‘s murder, Ali Harbi Ali, was previously referred to Prevent, something the Home Office has refused to confirm.

Home Secretary Priti Patel has said an ongoing review into the scheme will ensure it is “fit for purpose”.

Sky News looks in detail at the programme, how it works and how it could be changed.

What is Prevent?

Prevent is a programme which aims to stop people becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism, reducing the threat to the UK in the process.

It was set up in the wake of the September 11 attacks in the United States and expanded after the 2005 London bombings.

Prevent deals with all forms of terrorism, including Islamist, extreme right-wing and what is referred to as Mixed, Unclear or Unstable (MUU) ideologies.

Anyone who is concerned that someone they know might be at risk can refer them to the scheme, such as a friend, family member, colleague or professional.

Since 2015, public bodies have a statutory duty to stop people being drawn into terrorism.

This includes councils, schools, universities, healthcare, prisons and probation and the police.

It means people who work in these sectors are required to report people they suspect are vulnerable to extremism.

Training is provided for people in these settings to recognise signs of possible radicalisation and how to meet this duty.

How does a referral work?

All referrals are handled by expert officers in local police forces.

Once one has been made, initial checks are carried out. If the individual is found to not be at risk of radicalisation, the case is closed.

If someone is deemed to represent a security threat, they will be referred to the police for further inquiries.

If it is established that there is a genuine risk of radicalisation, the case is considered by a “Channel Panel”, a multi-agency group of professionals who assess the risk and decide on a package of support to offer the individual.

This support works in a similar way to programmes designed to protect people from gang activity, drug or sexual abuse.

Follow the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Participation in Channel is voluntary, while those who are referred to Prevent have to give consent (through a parent or guardian if they are underage) before they can be given support.

If an individual wants to get advice before referring someone, they can speak to a range of people, including a local authority safeguarding team, a teacher, healthcare provider or another trusted authority.

Getting in touch with these authorities will not get the person in trouble if no criminal offence has taken place.

A referral does not show up on criminal records checks and has no bearing on the individual’s future prospects.

How many people are referred?

In the year ending 31 March 2020, 6,287 referrals relating to 6,068 individuals were made to Prevent.

This is a 10% increase from the previous year (5,737).

Most of the referrals came from the police (1,950, 31%) and the education sector (1,928, 31%), while more than half were for individuals aged 20 and under (54%) and the overwhelming majority were males (88%).

A total of 51% of the referrals were related to MUU ideologies, 24% to Islamist radicalisation and 22% to extreme right-wing radicalisation.

A total of 1,424 cases went to a “Channel Panel”, of which 697 were progressed further.

Of these 43% were to do with extreme right-wing radicalisation (302), 30% were related to Islamist radicalisation (210), 18% were classified as MUU ideology (127) and the remaining 8% were to do with other radicalisation concerns (58).

Between 2015 and 2020, 2,352 individuals identified as vulnerable to radicalisation were supported by Prevent.

Has there been criticism of it?

Critics of Prevent argue it is counterproductive and does not work, sowing distrust within the Muslim community in particular.

A coalition of 17 groups announced earlier this year that they would be boycotting the independent review of Prevent.

In a joint letter, the organisations said they have “long raised concerns about the discriminatory and anti-Muslim impact of Prevent and its potential to violate core human rights”.

Liberty, one of the campaign groups that signed the letter, has called for the “fundamentally misconceived” scheme to be scrapped, arguing ministers have not “published any evidence that holding extreme views is a reliable predictor of future participation in violence”.

“The policy simply embeds discrimination in public services, eroding carefully cultivated relationships which rely on trust, and fosters a culture of self-censorship,” Liberty said.

But Peter Neumann, a professor of security studies at King’s College London, said scrapping Prevent is not the answer.

“I think Prevent does work in many cases, and I think it’s an unfair expectation to have to believe it works 100% of the time – no government programme ever works 100% of the time,” he told the Associated Press.

“So one case of failure doesn’t necessarily mean the whole program is rubbish.

“But it is equally wrong to just say everything is fine and let’s just carry on. There are problems with Prevent. It needs to be reviewed, and it should be reinvented.”

Nick Aldworth, a former counter-terrorism chief, has told Sky News there is a “gap in the market” in the lack of referrals to Prevent from family members.

“Typically about 30% of referrals come from education… about 30% come from the police and about 30% come from a disparate number of places including health,” the UK’s former counter-terrorism national co-ordinator said.

“The interesting point is that only between 2-5% come from family and friends and the workplace. Of course, that’s the point you would expect changes in people’s behaviour to be most observable.

“That’s where the gap in the market is.”

A Home Office spokesperson told Sky News that Prevent “remains a vital tool for early intervention and safeguarding, and the police and security services work day and night to keep us safe from those who would do us harm”.

They added that the findings of the review will be presented to the government in “due course”, with the report expected to be published before the end of the year.

What is its future?

Prevent is currently the subject of an independent review, led by former Charity Commission chairman William Shawcross, meaning changes could be made in the near future.

Speaking when he was appointed in January, Mr Shawcross said: “As Independent Reviewer, I look forward to assessing how Prevent works, what impact it has, and what further can be done to safeguard individuals from all forms of terrorist influence.”

He added: “I intend to lead a robust and evidence-based examination of the programme, to help ensure that Britain has a clear and effective strategy to protect vulnerable people from being drawn into terrorism.”

Speaking to Sky News about this review, the home secretary said: “It’s timely to do that, we have to learn, we obviously constantly have to learn, not just from incidences that have taken place but how we can strengthen our programmes.”

She added: “We want to ensure that it is fit for purpose, robust, doing the right thing.

“But importantly learning lessons, always building upon what is working and addressing any gaps or issues where the system needs strengthening.”

What could change?

According to a report in The Times on Tuesday, the independent review is set to criticise the current multi-agency approach as too soft on intervention.

It will recommend that MI5 and counterterrorism police should be given an increased role in deciding whether further action should be taken against individuals referred to Prevent, according to the report.

A former justice secretary has said the programme needs improvements to make it more effective.

Robert Buckland has called for increased cooperation between schools, the health service and other public agencies to put the security services in a better position to intervene early on and prevent attacks from happening.

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer raised the issue of the government’s anti-terror strategy at PMQs on Wednesday, pointing out that ministers had yet to respond to recommendations from the commission for countering extremism made eight months ago.

This said that new laws were needed to stop hate groups from “operating with impunity”.

The commission said extremists were exploiting gaps between the current legislation around hate crime and terrorism.

Source: Read Full Article