Obituary for an Icelandic glacier

Mourners have gathered in Iceland to commemorate the loss of Okjokull, which has died at the age of about 700.

The glacier was officially declared dead in 2014 when it was no longer thick enough to move.

What once was glacier has been reduced to a small patch of ice atop a volcano.

Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdottir, Environment Minister Gudmundur Ingi Gudbrandsson and former Irish President Mary Robinson attended the ceremony.

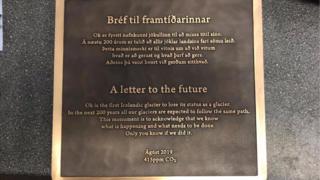

After opening remarks by Ms Jakobsdottir, mourners walked up the volcano northeast of the capital Reykjavik to lay a plaque which carries a letter to the future.

“Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as glacier,” it reads.

“In the next 200 years all our main glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done.

“Only you know if we did it.”

The dedication, written by Icelandic author Andri Snaer Magnason, ends with the date of the ceremony and the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air globally – 415 parts per million (ppm).

Interactive

See how Iceland’s Okjokull has shrunk

August 2019

September 1986

“You think in a different time scale when you’re writing in copper rather than in paper,” Mr Magnason told the BBC. “You start to think that someone actually is coming there in 300 years reading it.

“This is a big symbolic moment,” he said. “Climate change doesn’t have a beginning or end and I think the philosophy behind this plaque is to place this warning sign to remind ourselves that historical events are happening, and we should not normalise them. We should put our feet down and say, okay, this is gone, this is significant.”

Oddur Sigurdsson is the glaciologist at the Icelandic Meteorological Office who pronounced Okjokull’s death in 2014.

He has been taking photographs of the country’s glaciers for the past 50 years, and noticed in 2003 that snow was melting before it could accumulate on Okjokull.

“Eventually I thought it was so low that I wanted to go up there and check myself. I did that in 2014,” he said. “The glacier was not moving – it was not thick enough to stay alive. We call that dead ice.”

The glaciologist explains that when enough ice builds up, the pressure forces the whole mass to move.

“That’s where the limit is between a glacier and not a glacier,” he says. “It needs to be 40 to 50 metres thick to reach that pressure limit.”

An Icelandic broadcaster accompanied Mr Sigurdsson to the glacier in 2014 to report the death of Okjokull. But the glaciologist says it “did not stir up very much attention”.

“I was a little surprised because this glacier was visible from densely inhabited areas and a good part of the Icelandic ring road,” he said. “It was also known to most kids because of its peculiar name and place on maps.”

Enter anthropologists Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer. The two professors from Rice University in Texas made a documentary about the loss of the glacier called Not Ok in 2018, and came up with the idea of a memorial during filming.

“Here was this really important story about this glacier that tells us something about the catastrophic changes we’re seeing all around glacial basins everywhere on the planet and yet the story wasn’t very well known,” Dr Howe told the BBC. “So part of the reason we wanted to make the movie was to get some more visibility for the phenomenon. And the plaque kind of followed in those footsteps.”

“People felt this was a real loss, and that it deserved some kind of memorial,” Dr Boyer said. “Plaques recognise things that humans have done, accomplishments, great events. The passing of a glacier is also a human accomplishment – if a very dubious one – in that it is anthropogenic climate change that drove this glacier to melt.

“It’s not the first glacier in the world to melt – there have been many others, certainly many smaller glacial masses – but now that glaciers the size of Ok are beginning to disappear, it won’t be long before the big glaciers, the ones whose names are well recognised, will come under threat.”

Glaciers have great cultural significance in Iceland and beyond. Snaefellsjokull, a glacier-capped volcano in the west of the country, is where characters in Jules Verne’s science fiction novel Journey to the Centre of the Earth found a passage to the core of the planet. That glacier is now also receding.

“My generation had to learn by heart the names of the most significant mountains, moors, fjords,” Mr Magnason explained. “So culturally it’s also referring back to childhood textbooks.

“The world that we learned how it was, learned by heart as some kind of eternal fact, is not a fact any more.”

Mr Sigurdsson made an inventory of Icelandic glaciers in the year 2000, finding there were just over 300 scattered across the island. By 2017, 56 of the smaller glaciers had disappeared.

“150 years ago no Icelander would have bothered the least to see all the glaciers disappear,” he said, as they advanced over farmlands and flooded whole areas with melt waters and streams. “But since then, while the glaciers were retreating, they are looked at as a beautiful thing, which they definitely are.

“The oldest Icelandic glaciers contain the entire history of the Icelandic nation,” he added. “We need to retrieve that history before they disappear.”

Source: Read Full Article