My dad might still be alive if mental health talk was ‘normalised’

A new study says “deaths of despair” among middle-aged Britons have more than doubled in the last 25 years.

The figure groups together suicide, alcohol-related illnesses and drug abuse – and collectively they are more deadly than heart disease.

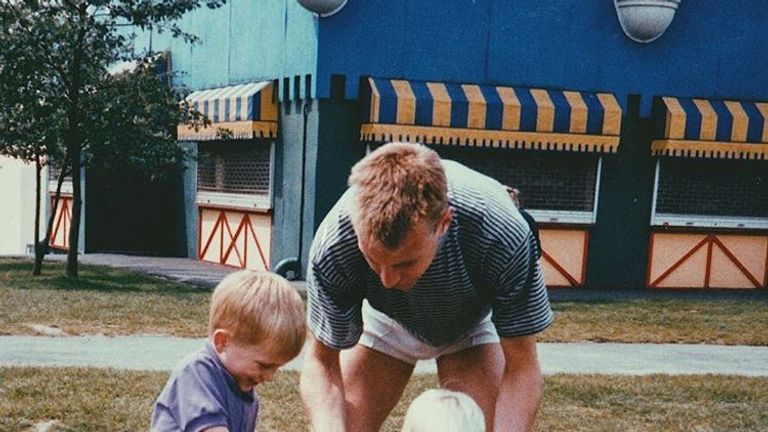

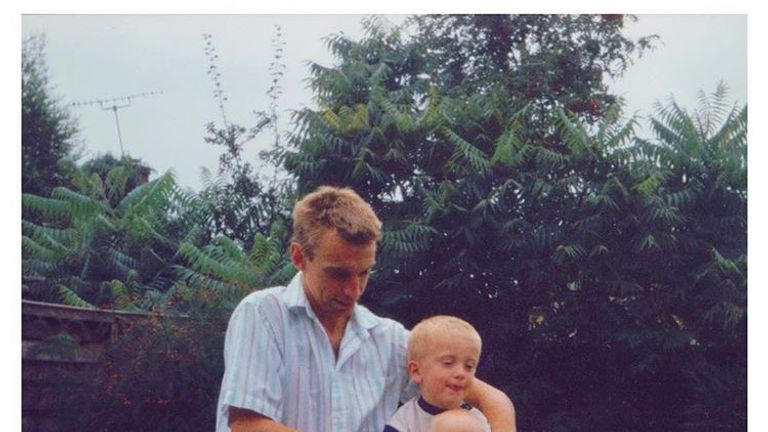

Paul McGregor’s dad died by suicide 10 years ago after seemingly having a “perfect” life.

He says mental illness must become a normal topic of conversation so that people don’t feel they have to suffer in silence.

Here is his story.

March 4th, 2009. I remember the day vividly. What was a normal day for most, was a life-defining day for me and my family.

My dad, the man I idolised, the man who to those around him had everything on paper, took his own life.

It was a suicide that shocked everyone who knew him, and for me, it was quite frankly the worst day of my life.

Growing up, my dad, Neil, never had any history of depression or mental illness and always seemed happy.

He was a full-time engineer by trade, he was a qualified physiotherapist too and ran a small practice from home in the evenings, he had a psychology degree, read self-help books, practised meditation and was a keen athlete.

As a family we were extremely close and Dad was loved by the many friends around him. From the outside in, everything seemed to be okay, in fact everything seemed ‘perfect’, but my dad was obviously suffering in silence.

Six months before my dad’s suicide everything changed.

His behaviour overnight went from the man we all knew to someone who was broken, showing clear signs of sadness and lacking hope.

He sought help from the doctors and was diagnosed with depression, being prescribed with anti-depressants.

He returned to the doctor as things hadn’t improved, his dose was increased. A few days later he attempted suicide for the first time.

The sudden nature of his attempt shocked us all, and even though he survived, the nightmare continued.

He continued to struggle with his depression and suicidal thoughts, and he was sectioned to the local mental health unit shortly after.

He spent a few months there.

As a family visiting him every single day, this was our first real exposure to mental illness as we heard stories and witnessed other patients.

I remember spending Christmas Day there with him, as a family. How was this happening? Maybe I was ignorant, but mental illness and suicide wasn’t something I ever thought would affect us.

When he was released things seemed better, but shortly after things got terribly worse, leading to his eventual suicide.

Struggling to deal with it personally I bottled it up. I found myself painting on a smile to show those around me I was okay, but I buried my head in a pillow night by night crying and wishing he was here.

My journey to work consisted of me emotionally distraught for most of the 40-minute drive, but walking into the office cracking jokes and showing I was managing it.

I buried the pain that came with his suicide, the grief I was struggling with, and hoped that it would go away.

Personally, it took me two years to openly talk to someone about what happened. Two years for me to show any real emotion to someone outside of my family. And since then, I’ve been ‘dealing’ with it.

I’m not over it, I don’t think I’ll ever get over it, but I’m managing it better than I’ve ever done before.

As men, we’re typically conditioned to feel that vulnerability is weakness. My dad struggled with his mental health for a while, intrusive thoughts that consumed him, but he felt like he couldn’t tell anyone. Not even his family.

If he told someone how he was feeling before his breakdown, how would he have been perceived? Weak? Unstable? I did exactly the same thing too.

Bottling up those emotions, putting on a mask, keeping myself busy to distract myself from the pain because that’s what I thought made me a man.

But 10 years on I’ve realised vulnerability is strength, it isn’t weakness. That any emotional pain we’re going through needs to be dealt with, it can’t be ignored.

I’ve also realised that we’re not alone. Mental health affects everyone, we all have it, and normalising the conversation around it will help those suffering in silence. Just like my dad did.

My dad will never come back, his suicide will be something I and my family have to live with for the rest of our lives. But I do know he could still be alive.

If the conversation was normalised, if he had earlier intervention and if got the support he so desperately needed, he could still be here today.

Suicide is the biggest killer of men under 45 right now. It’s also the biggest killer of young people.

Simply put, the biggest threat to my life as a 29-year-old male is myself – my mental health – it’s suicide.

But we need to talk. Because even if – like I did – you think mental illness or suicide may never affect you, the statistics show that there’s a big chance it could.

Looking forward, I’m hugely grateful for the amazing dad I had in my life for 18 years. I’m grateful for the family I still have today, and I’m hoping that sharing this story can help others. Because if it can help just one, it makes reliving it worthwhile.

:: Anyone feeling emotionally distressed or suicidal can call Samaritans for help on 116 123 or email [email protected] in the UK. In the US, call the Samaritans branch in your area or 1 (800) 273-TALK.

Source: Read Full Article