MH17 plane crash in Ukraine: What we know

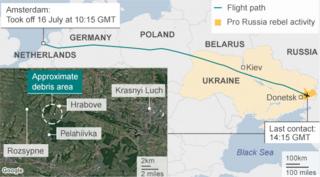

Flight MH17, en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur, was travelling over conflict-hit Ukraine on 17 July 2014 when it disappeared from radar.

A total of 283 passengers, including 80 children, and 15 crew members were on board.

The Malaysia Airlines plane crashed after being hit by a Russian-made Buk missile over eastern Ukraine, a 15-month investigation by the Dutch Safety Board (DSB) found in October 2015.

In September 2016, an international team of criminal investigators said evidence showed the Buk missile had been brought in from Russian territory and was fired from a field controlled by pro-Russian fighters.

The Dutch-led joint investigation team concluded in May 2018 that the missile system belonged to a Russian brigade, and Australia and the Netherlands announced both were holding Russia responsible for downing the aircraft.

But investigators are still trying to establish who precisely the perpetrators were, and have appealed for witnesses to come forward to assist the continuing investigation.

Russia has denied any role and says the missile was fired from Ukrainian-held territory.

What happened?

According to Dutch air accident investigators, the plane left Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport at 10:31 GMT (12:31 local time) on 17 July and was due to arrive at Kuala Lumpur International Airport at 22:10 GMT (06:10 local time).

The safety board said the plane lost contact with air traffic control at 13:20 GMT, when it was about 50km (30 miles) from the Russia-Ukraine border.

Malaysia Airlines initially said the plane lost contact at 14:15 GMT.

Footage emerged of the crash site in the Donetsk area of Ukraine – territory controlled by Russian-backed separatists – and witnesses spoke of dozens of bodies on the ground.

More amateur footage emerged, though not until 16 November, of the moments after MH17 went down.

What caused the crash?

The DSB said a missile exploded just above and to the left of the cockpit, causing the plane to break up in mid-air.

It said the crash was caused by the detonation of a Russian-made 9N314M-type warhead carried on the 9M38M1 missile, launched from the eastern part of Ukraine using a Buk missile system.

The Joint Investigation Team (JIT) which reported on the interim findings of its criminal investigation in September 2016 similarly found “irrefutable evidence” a BUK missile from the 9M38-series was used.

The weapon system used was identified from the damage pattern on the wreckage, as well as fragments of shrapnel found. Traces of paint on a number of missile fragments found matched the paint on parts of a missile recovered in the area.

Investigators simulated various trajectories of the warhead to establish where it exploded and found that a 70kg warhead best matched the damage observed on the wreckage.

They showed it exploded about four metres above the tip of the aeroplane’s nose on the left of the cockpit, showering the plane with fragments of the warhead.

The forward section of the plane was penetrated by hundreds of high-energy objects from the warhead, killing the three crew in the cockpit immediately and causing the plane to break up in stages:

Investigators believe it was between 60 and 90 seconds after the cockpit came off that the rest of the aircraft hit the ground.

Who do investigators blame?

The plane crashed in rebel-held eastern Ukraine at the height of the conflict between government troops and Russian-backed separatists.

The Dutch report commissioned three separate investigations – from Dutch, Russian and Ukrainian bodies – to look at where the missile launcher could have been located. It said the missile could have been fired from an area of about 320 sq km in the east of Ukraine.

The JIT and the government in Ukraine say the missile was brought from Russia and launched from the rebel-held part of eastern Ukraine.

In June 2016, the JIT published a photo of a large Russian-made Buk missile component found at the crash site.

In its September 2016 report, the team used witness testimony, intercepted phone calls, photographs and satellite imagery showing scorched land to pinpoint the launch site on high ground at Pervomaiskyi, near Snizhne, in territory held by pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine.

It said it had been able to track the course of the missile trailer from Russia to the launch site and immediately back into Russian territory following the downing of the plane.

Then in May 2018, Dutch investigators concluded that the missile belonged to a Russian brigade, the 53rd Anti Aircraft Missile brigade based at Kursk.

Moscow’s defence ministry rejected the allegation, and has previously insisted that none of its weapons were used to bring down MH17. But the team of international investigators found that “all the vehicles in a convoy carrying the missile were part of the Russian armed forces”.

“On the basis of the [joint international team’s] conclusions, the Netherlands and Australia are now convinced that Russia is responsible for the deployment of the Buk installation that was used to down MH17,” Dutch foreign minister Stef Blok said.

Investigators have called on Russia to fully cooperate with the probe. After Russia claimed it had evidence the rocket was fired from Ukrainian-held territory, they promised to review any evidence the country could provide.

As for the identities of the perpetrators, the JIT has identified a “long list” of 100 possible suspects. It is continuing its work, including trying to identify the perpetrators’ chain of command, and has appealed for witnesses to come forward – saying those who co-operate could face lower jail terms or immunity from criminal liability themselves.

What does Russia say in response?

Russian officials and Russian-backed rebels reject accusations of involvement, with the Russian foreign ministry saying the JIT investigation is “biased and politically motivated”.

The Russian firm that manufactures Buk missiles has insisted the missile was a model no longer used by Russian forces and said its own investigation showed it had been fired from Ukrainian-controlled territory.

And two days before the JIT was due to publish its interim findings in September 2016, Russia produced radar images which, it argued, showed that the missile could not have come from rebel-held areas.

Radar experts appointed by examining magistrate backed up the JIT findings. Commentators, meanwhile, pointed out that Russian officials had given different versions of events since the plane was shot down.

What type of plane was it?

The aircraft was a Boeing 777-200ER, the same model as Malaysia Airlines flight MH370, which disappeared while travelling from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing in March 2014.

The plane, manufactured in 1997, had a clean maintenance record and its last check was on 11 July 2014, Malaysia Airlines said.

Malaysia’s prime minister said there was no distress call before the plane went down.

How about the wreckage?

Parts of the plane were found distributed over an area of about 50 sq km.

Where debris from MH17 was found

Following the crash, there was an international outcry over the way rebels handled the debris site, leaving passengers’ remains exposed to summer heat and allowing untrained volunteers to comb through the area.

This led to weeks of delays in the removal of the wreckage, but a deal made with local militias eventually allowed the work to begin.

The spread of MH17 debris near Hrabove

Crash site near village

Debris in field

Tail piece

Satellite image of MH17 debris

Crash site near village

Satellite images taken by DigitalGlobe on 20 July appear to show the large debris field near the village of Hrabove.

Debris in field

About 700 metres (2,296ft) down the road from the village is another patch where bodies and debris have been found.

Tail piece

A piece of Flight MH17’s tail, with the Malaysia Airlines marking, is seen lying on its own about 100m (330ft) south of the other debris.

Who was on board?

The 298 who perished

Malaysia Airlines’ passenger list shows flight MH17 was carrying 193 Dutch nationals (including one with dual US nationality), 43 Malaysians (including 15 crew), 27 Australians, 12 Indonesians and 10 Britons (including one with dual South African citizenship).

There were also four Germans, four Belgians, three Filipinos, one Canadian and one New Zealander on board.

At least six of those killed were delegates on their way to an international conference on Aids in Melbourne, Australia.

Professor Joep Lange – a prominent scientist and a former president of the International Aids Society (IAS) – was among those who died.

His colleagues described him as “a great clinical scientist” and “a wonderful person and a great professional”.

Other passengers and crew included a Malaysia-Dutch family of five, a Dutch couple on their way to Bali, an Australian pathologist and his wife returning from a European holiday, as well as a Malaysian flight steward whose wife – who also works for Malaysia Airlines – had narrowly escaped death when she pulled out of a shift working on missing flight MH370.

Was it safe to fly over Ukraine?

The DSB has suggested there was sufficient reason to close the airspace above eastern Ukraine because of the conflict.

In the months leading up to the crash, the conflict in Ukraine had expanded into the airspace and a number of military aircraft had been shot down

Although the area where the jet crashed had a no-fly zone in place up to 9,754m (32,000ft), the airliner was flying above the limit at 10,058m (33,000ft).

The airspace over eastern Ukraine was busy with commercial flights that day – 160 planes flew over the region.

The flight tracker Planefinder shows how busy the airspace was in the 48 hours leading up to the disaster.

According to Flight radar24, which also monitors live flight paths, the airlines that most frequently flew over Donetsk in that week were: Aeroflot (86 flights), Singapore Airlines (75), Ukraine International Airlines (62), Lufthansa (56), and Malaysia Airlines (48).

At the time of the MH17 crash there were three other commercial airliners flying in the vicinity.

Selected flights over eastern Ukraine on the afternoon of 17 July

What about the plane’s black boxes?

Russian-backed separatists handed over the plane’s “black box” flight recorders to Malaysian investigators, who in turn passed them on to Dutch authorities.

The recorders – actually coloured a deep orange to aid discovery – store key technical information about the flight as well as conversations in the cockpit.

According to the DSB, the flight data recorder showed that “all engine parameters were normal for cruise flight” until the recording “stopped abruptly at 13.20:03 hrs”.

No spoken warnings were found on the cockpit voice recorder.

Who is investigating?

Observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) – whose job it was to observe the site ahead of the arrival of investigators – were the first team to visit the debris zone, however their movements were restricted by militiamen.

Responsibility for the investigation belongs to the state within which an incident occurs, according to the International Civil Aviation Organization.

As such, the Ukrainian government initiated that probe, but the DSB was asked to head the main investigation, as the majority of victims were from the Netherlands.

The separate, Dutch-led JIT has been gathering evidence for a possible criminal trial.

In July 2015, Russia vetoed a draft resolution at the UN Security Council to set up an international tribunal into the disaster. President Vladimir Putin said it would be “premature” and “counter-productive”.

Source: Read Full Article