Manchester Arena bomber and brother ‘shared goal to kill’, court hears

The Manchester Arena bomber and his brother “had a shared goal” to kill and injure as many people as possible in the 2017 atrocity, a trial has heard.

Hashem Abedi, the brother of the Manchester Arena bomber, appeared in court on the first day of his trial on Tuesday accused of 22 counts of murder.

The 22-year-old is charged with helping his brother build the bomb which killed his brother and 22 men, women and children in the foyer outside the venue after an Ariana Grande concert.

Abedi is also accused of the attempted murder of other concert goers at the venue in May 2017 and conspiracy to cause explosions. He denies the charges.

Duncan Penny QC said Abedi was “just as responsible for this atrocity and for the offences identified in the indictment – as surely as if he had selected the target and detonated the bomb himself”.

He said while the target may have been selected by Salman Abedi alone, the brothers had a “shared goal” to “kill, maim and injure” as many people as possible by the detonation of a large homemade bomb in a public place.

Mr Penny said it was the prosecution’s case that Abedi was “just as guilty of the murder of the 22 people killed as was his brother”.

“He is equally guilty of the attempted murder of many others, and in doing so, he was guilty of agreeing with his brother to cause an explosion.”

The defendant appeared in court wearing a black collared shirt, jeans and glasses, with a small goatee beard.

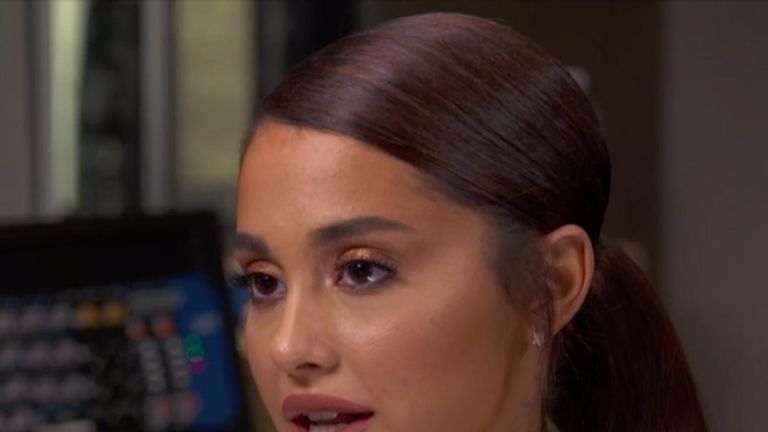

Singer Grande, 26, was said to have an “extremely large UK fan base of all ages, including the very young”.

The court heard that “the large and diverse nature of the fan base was a fact that was well-known and widely publicised”.

The jury was told that the victims included men, women, teenagers and a child. There were 237 people physically injured, 91 of them seriously or very seriously.

Another 670 people reported psychological trauma, bringing the total affected to nearly 1,000.

Abedi is accused of obtaining the ingredients, or “precursor chemicals”, for the construction of the bomb, using other peoples bank details and online accounts created in fictitious names.

The device was manufactured from a mixture that included hydrogen peroxide and sulphuric acid, which were “readily available to buy from wholesalers and on the internet”.

It used a cylindrical tin used as a homemade detonator packed with nuts, cross dowels and screws as shrapnel to “maximise the potential harm to victims”.

In mid-April, the brothers also bought a Nissan Micra to use as a “de-facto storage facility”.

The explosion was the “culmination of months of planning, experimentation and preparation by the two of them,” the court heard.

Mr Penny continued: “The bomb was detonated and was self-evidently designed to kill and maim as many people as possible.

“It was packed with lethal shrapnel and it was detonated in the middle of a crowd in a very public area – the intention being to kill and to inflict maximum damage.”

He added: “In acting as he did, the Crown alleges that this defendant assisted and encouraged his brother to act as he did.”

The City Room, where Salman Abedi set off the bomb, was a foyer area that acted as a point for parents and family to collect young concert goers, the trial heard.

It was said to be a “natural assembly point within the complex for people to gather at the conclusion of the concert in order to meet up with or to collect their loved ones” and was heavily congested with people.

“In the midst of these people, carrying a heavy rucksack that contained a homemade bomb was Salman Abedi,” Mr Penny said.

After the bombing, police identified a series of different addresses in Manchester which the brothers had used to receive deliveries, construct prototypes, store materials, and manufacture explosives.

The pair were living along in the family home in Fallowfield, South Manchester, after their parents had returned to live in Libya in 2016.

Abedi was detained in Libya on the day after the bombing and extradited back to Britain last July.

Abedi worked occasionally at a pizza takeaway in Stockport, where he asked the owner if he could take the empty and discarded metal vegetable oil cans and sell them for scrap.

The owner was happy to let Abedi have them to save him the trouble of disposing of them, the court was told.

The prosecutor showed the jury a 20 litre can of Consumer’s Pride vegetable cooking oil and told them that the scrap metal value of the cans was negligible.

If weighed in bulk, it would fetch around 18p, but the use to which the cans were put at the family home was “much more sinister”, Mr Penny said.

A 7cm long piece of twisted metal from one of the cans, labelled “Can F” was found in some green fabric in the corner of the City Room after the explosion.

The trial continues.

Source: Read Full Article