Hunting for truth in a land of conspiracy

A headscarved woman whose baby was kicked while she was urinated on by anti-government demonstrators.

Veteran political activist Noam Chomsky championing President Erdogan in a newspaper interview.

Photos of bloated corpses of Muslims in a river in Myanmar. A video showing Turkish jets blowing up Kurdish fighters in Syria.

All were compelling and widely-shared stories in Turkey. All were completely false.

Turkey is a country where fact and fiction are increasingly hard to distinguish, and where information is weaponised to further divide a profoundly polarised society.

Why Turks are besieged by ‘fake news’

It is little wonder that Turkey ranks first in a list of countries where people complain about completely made-up stories, according to this year’s Reuters Digital News Report.

Almost half its people – 49% – say they faced “fake news” in the week before the survey was taken. In Germany, it is just 9%.

Every day brings new outlandish and unverified claims in the media.

This is fodder for a nation addicted to conspiracy theories – where a senior adviser to Mr Erdogan claimed the president’s enemies were trying to kill him with telekinesis and that foreign TV chefs were spies.

Inflammatory rhetoric pervades the media, 90% of which is estimated to be pro-government. That is because opposition outlets have been steadily shut down, branded “terrorist propaganda”, or financially crippled.

Newspapers that survive serve not as models of journalism but as government mouthpieces, which were recently handed the leaks from the killing of Jamal Khashoggi. That led the world to swallow what they printed, rather than treating them with the usual caution.

Turkey is the world’s largest jailer of journalists, ranking 157 of 180 countries in the press freedom index of the watchdog Reporters Without Borders.

Just 38% here trust the news, the Reuters study shows.

How a website debunked 500 fake stories

Fertile ground, then, for Turkey’s first independent website devoted to fact-checking online material. Teyit.org takes its name from the Turkish word for confirmation.

Founded in 2016 by a young journalist, Mehmet Atakan Foca, its team probes the authenticity of photographs and stories that circulate online.

Foca, who did an internship at the BBC Turkish service, says they now get more than 30 tip-offs a day about suspicious-looking material, and use a variety of core journalistic skills and digital technology to check them.

“To tackle the problem of fake news, it’s not enough to publish articles about misinformation,” he says. “We want to educate people and give them the tools to strengthen their capacity for verification.”

Over the past two years, Teyit has debunked 526 false stories. Many are political, using doctored photographs or false social media claims about politicians.

Others have even more serious consequences.

This story is part of a series by the BBC on disinformation and fake news – a global problem challenging the way we share information and perceive the world around us.

For more visit www.bbc.co.uk/beyondfakenews

When photos of three men were published online and labelled as those who killed 39 people in an attack on Istanbul’s Reina nightclub, Teyit traced the men and disproved the allegations.

One of the wrongly accused, Metehan Alim, told us a defamation case against six media outlets is ongoing.

“Turks are fundamentalists with our beliefs,” he told the BBC. “We want to read what we already believe. We resist science or facts. We believe in myths instead.”

Some of the stories debunked by Teyit are international.

At the height of the violence in Myanmar against Rohingya Muslims, the Turkish finance minister tweeted photos that allegedly showed victims. Teyit discovered they were from elsewhere.

The Myanmar government formally complained and the minister was forced to delete the tweet.

Even former Ankara mayor Melih Gokcek, notorious for conspiracy theories, retracted a tweet showing a photograph purportedly of flood damage to a road. It had been debunked by Teyit, and he even credited the fact-checking website.

ARKADAŞLAR,

BİR ALTTAKİ TWİTİMDE VERDİĞİM ÇÖKME FOTOSUNU GOOGLE’DAN VE MEDYADAN ALDIM.⤵️

ANCAK https://t.co/JHvHP5xp8G BUNUN SON SELLE İLGİLİ OLMADIĞINI YAZMIŞ.

BEN DE HATAYI DÜZELTİYORUM.

ANCAK O ÇÖKME NEREDE OLURSA OLSUN KESİN MÜTEAHHİT VE KONTROL MEMURU HATASIDIR. pic.twitter.com/6INQ5sdkyx

End of Twitter post by @06melihgokcek

How I became a target for fake news

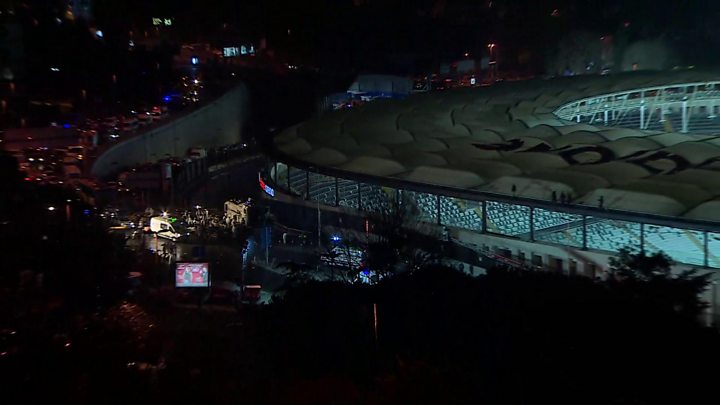

But I am still waiting for Mr Gokcek to retract his unfounded claim that the BBC rented a hotel room overlooking Besiktas football stadium just before it was attacked by suicide bombers in 2016.

Supposedly, that allowed me to broadcast live within minutes – and suggested that we were complicit or knew of it in advance.

The absurd allegation was disproved by Teyit, showing my first live broadcast from our BBC office 90 minutes after the attack and debunking a video that falsely translated my words.

After four years in Turkey, I’m getting used to such baseless claims.

Pro-government dailies frequently allege I’ve been sent from London as a provocateur to stir up social unrest.

One needs a thick skin in this country.

Rise of the ‘fake fact-checkers’

“News literacy is very low in Turkey,” says Mehmet Atakan Foca. “It’s more about propaganda. People live in an echo chamber, accusing others of being terrorists or pro-government, creating false stories to strengthen their opinions.”

Even fact-checking itself is used as a tool in a country riven by mistrust and division.

One website claims to be an independent verifier of news, but is actually run by a prominent columnist for Sabah, the main pro-government daily, and her husband. Instead of authenticating sources or photographs, it pushes the government line, discrediting perceived criticism of President Erdogan.

“There is no freedom of information in Turkey”, Mr Foca says, “so fake fact-checking websites are used as propaganda.”

“They’re another weapon of government”, he adds.

Controlling information, peddling false stories, fuelling the “us and them” narrative: these are all tactics of authoritarian governments.

They are all major challenges for the fact-checkers aiming to go beyond fake news.

Source: Read Full Article