How Spain’s ‘Angel of Budapest’ saved Jews from Holocaust

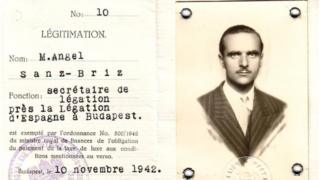

Thousands of Holocaust survivors and their descendants escaped the Nazis thanks to a Spanish diplomat nicknamed “the Angel of Budapest” – yet the late Angel Sanz Briz is hardly known in Spain today.

His improvised heroics in 1944 saved more than 5,000 Hungarian Jews from deportation to Auschwitz.

“He is a hero of greater stature than Schindler,” says Eva Benatar. Her mother sheltered her as a baby just weeks old and her brother in one of the safe houses set up by Sanz Briz in Nazi-occupied Budapest.

Oskar Schindler was a German industrialist who managed to save more than 1,000 Jews from the Holocaust. His story was told in the Hollywood movie Schindler’s List.

After the Nazi invasion on 19 March 1944, codenamed Operation Margarethe, the chief SS Holocaust organiser Adolf Eichmann moved to Budapest with a plan to eliminate Hungary’s roughly one million Jews in record time.

Sanz Briz was serving in Spain’s embassy as commercial attaché, before being left in charge of the mission in mid-1944 at the age of 33. He was one of a group of diplomats who decided to rescue Hungarian Jews.

In a matter of weeks the SS deported more than 400,000 Jews to Auschwitz.

One of the Spaniard’s fellow humanitarian conspirators became a household name – Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who issued “protective passports” and saved tens of thousands of Jews.

Wallenberg later disappeared; he was seized by occupying Soviet forces and is widely thought to have died in a Soviet jail.

Why Sanz Briz took law into his own hands

As reports grew about the escalating Holocaust at Auschwitz and other Nazi killing sites, Sanz Briz started informing the fascist Franco government in Spain about the appalling truth.

A key document he sent was the Vrba-Wetzler report, by two Jewish escapees from Auschwitz.

However, for several months he received no instructions from a regime that had initially backed Hitler in the war.

Remarkably, he began to take the law into his own hands, falsifying consular documents to grant nationality to refugees on the basis of a long-expired 1924 Spanish law aimed at Sephardic Jews, even though Hungary’s Jewish community was overwhelmingly Ashkenazi.

Jews were hidden in the Spanish embassy in Buda, bribes were paid to local officials. Sanz Briz braved the dangers of Nazi and Hungarian fascist Arrow Cross patrols, as well as Allied bombing raids, to shelter Jews at risk.

“I managed to get the Hungarian government to authorise the protection by Spain of 200 Sephardic Jews. Then I turned those 200 units into 200 families; and those 200 families were multiplied indefinitely, through the simple procedure of not expediting any safe conduct to Jews with a number higher than 200,” Sanz Briz wrote in his report for the Spanish government from Berne in December 1944.

“He added letters to each number, using the whole alphabet,” explains the diplomat’s son, Juan Carlos Sanz Briz.

“It was quite out of character; he was actually a stickler for legality. Diplomats aren’t meant to issue false papers or put the national flag on buildings not part of the diplomatic mission.

Safe houses

Sanz Briz’s meticulously recorded final tally came to 232 provisional passports issued to 352 people, as well as 1,898 protective letters, and 15 ordinary passports for 45 Sephardic Jews.

As the Nazis and Hungarian fascists closed in on the city’s Jews, moving them into confined quarters and killing people in the streets, Sanz Briz rented 11 apartment buildings to house the approximately 5,000 people he had placed under Spain’s protection.

In a 2013 interview for Spain’s RNE public radio, Jaime Vándor (recently deceased), who moved to Barcelona with his family after the war, recalled the squalor of those Spanish refuges.

“There were 51 of us living in a flat with two and a half rooms. We were crowded, hungry and cold, infested with fleas. The hygiene was appalling, obviously, with so many people using one toilet. But the worst thing was the fear, the fear of deportation.”

Ms Benatar’s mother was one of those granted papers by the Spanish embassy after she brandished a postage stamp from Madrid, where Eva’s grandmother had fled before the Nazi invasion.

Born in a cramped cellar, she never met her father, who died in the so-called death marches in early 1945.

But baby Eva, her mother and brother were able to escape Hungary, ending up in Tangier, then an international city, although the family eventually settled in Spain.

Posthumous recognition

Sanz Briz left Budapest in November 1944, ordered out by his superiors in Madrid, who feared he would suffer reprisals from the approaching Soviet army, due to Spain’s help for the Germans on the Eastern front.

He retreated into a regular diplomatic career, and was not permitted by the stridently anti-Israel Franco regime to receive the honour of Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial centre, in his lifetime.

He joined the ranks of the righteous in 1966.

An obituary for Sanz Briz published by Spain’s ABC newspaper in 1980 makes no mention of his exploits in Budapest.

“I never talked about this subject with him. It was not something that was discussed at home,” says Juan Carlos Sanz Briz. “He must have suffered greatly, but he didn’t tell us that.”

Spain and the Holocaust

Before Spain returned to democracy in the mid-1970s, the Franco regime had an ambivalent stance on its role in the Holocaust, sometimes claiming that Gen Franco had in fact been a saviour of Jews.

When the Nazis began deporting Jews from France, the Franco regime at first allowed many thousands to flee through Spanish territory, before tightening the policy in 1940.

Jews were refused transit papers, and those caught in the country illegally were rounded up and sent to a concentration camp at Miranda de Ebro.

At no time was any significant number of Jews given the option of refuge in Spain, not even Spanish-speaking Sephardic Jews from the Nazi-occupied Greek city of Thessaloniki.

But there is evidence that Franco began to sense the need to improve his regime’s international image as it became increasingly clear that Hitler was losing the war.

On 24 October, 1944, then foreign minister José Félix de Lequerica sent a telegram to Sanz Briz in Budapest. “On request of the World Jewish Congress please extend protection to largest number persecuted Jews,” it said.

Source: Read Full Article