Five reasons why Orthodox Church split matters

The Russian Orthodox Church has cut ties with the Church leadership in Istanbul, the Constantinople Patriarchate traditionally regarded as the Orthodox faith’s headquarters.

The Moscow-based Russian Orthodox Church has at least 150 million followers – more than half the total of Orthodox Christians.

The dispute centres on Constantinople’s decision last week to recognise the independence of Ukrainian Orthodox worshippers.

Just another arcane theological dispute, you might think. Well, there is more to it than that.

It’s part of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine

The drive for Ukrainian Orthodox independence intensified in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and Russia-backed separatists seized a big swathe of territory in eastern Ukraine.

Ukrainian government troops remain in a tense stand-off in the east and Russian rule in Crimea, unrecognised internationally, has triggered wide-ranging sanctions against Moscow.

The Russian Orthodox Church accuses Ukrainian nationalists of numerous attacks on its churches.

Weakening Moscow’s influence over Ukrainian worshippers has been an integral part of Ukraine’s statehood since the ex-Soviet republic became independent in 1991.

Now it’s personal

Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko says Church independence – officially called “autocephaly”- is “an issue of Ukrainian national security”. He called the Constantinople Patriarchate’s decision of 11 October “a great victory for the devout Ukrainian nation over the Moscow demons, a victory of good over evil, light over darkness”.

Many Ukrainians see the Moscow branch of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church as a tool of the Kremlin. But the Moscow Patriarchate argues that it has legal authority over the Ukrainian Church, dating back to 1686, and that Kiev was the birthplace of the Russian Orthodox Church.

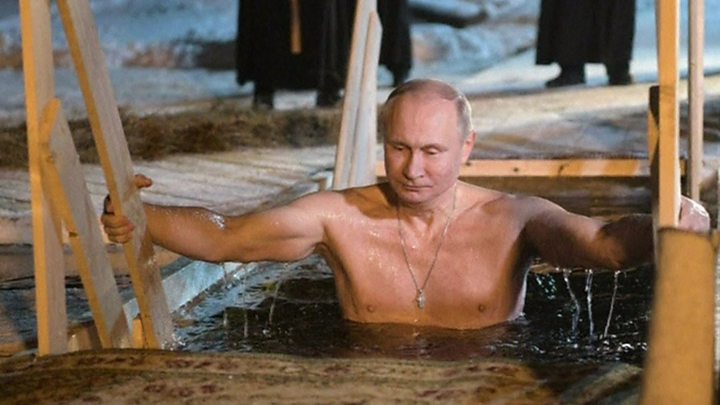

President Vladimir Putin has boosted the Russian Orthodox Church’s prestige and many of its priests identify closely with his nationalist agenda. Sometimes they ceremonially bless Russian military jets and space rockets.

He is close to Patriarch Kirill, the Russian Church’s leader, and has gone on pilgrimages to Mount Athos and other famous Orthodox sites.

Mr Putin participates in big Church celebrations for Easter, Epiphany and Christmas.

There could be fights over church property

There are fears that, with a full-blown dispute between Church authorities, congregations could be shut out of certain churches.

President Poroshenko accuses the Kremlin of trying to foment a religious war, and he has warned that Russian agents could try to seize church property.

The Moscow Patriarchate says its worshippers should no longer attend any services conducted by clergy loyal to Constantinople. From now on it will also boycott joint Orthodox Church ceremonies.

Mr Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov said the Kremlin would defend “the interests of Russians and Russian speakers and the interests of the Orthodox”, but only by using “political and diplomatic measures”.

Russia also said it had to protect ethnic Russians ahead of its military intervention in Ukraine in 2014.

So there is potential for serious conflict, not least because Ukraine’s Orthodox believers are divided among three Churches: the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), the Orthodox Church of the Kiev Patriarchate and the small Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC).

Constantinople’s move “is a big blow for Russia”, Marat Shterin, a religious studies expert at King’s College London, told the BBC.

“Russia’s use of culture in foreign policy is very important – the sense of identity, of being part of a bigger Orthodox world.”

Millions are affected

The estimated 150 million followers of the Moscow Patriarchate make Russia a leader in the Orthodox world, which numbers at least 260 million.

But traditionally Constantinople has been seen as “first among equals”. And it is now backing the creation of a new unified Orthodox Church based in Kiev.

In Ukraine the Moscow Patriarchate controls about 12,000 parishes, while the Kiev Patriarchate has about 5,000 and the UAOC nearly 1,000.

But Mr Shterin, who lectures on trends in ex-Soviet republics, says some Moscow-linked parishes will probably switch to a new Kiev-led church, because many congregations “don’t vary a lot in their political preferences”.

Religious tensions could spread to the Balkans

The Constantinople-Moscow split is a difficult issue for many Orthodox churches in Eastern Europe, Mr Shterin says. And their leaders will have to take sides.

The Serbian Church is close to Moscow; the Greek Church less so, but many Greek clergy feel close to both Russia and Serbia.

Constantinople has annulled the transfer of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church to Moscow’s jurisdiction, which happened in 1686.

That means the Kiev Patriarchate stands to win back parishes not only in Ukraine but also in parts of Belarus and Lithuania, which it controlled before the Russian empire expanded.

Source: Read Full Article