David Fuller: How was one of Britain’s most prolific sex offenders caught and how did he get away with it for so long?

For 34 years, one of Britain’s most prolific sex offenders believed he had got away with the murder of two women and the sexual assault of dozens of corpses.

It was only after a breakthrough DNA sample led detectives to electrician David Fuller, did the full extent of his crimes finally come to light.

How was he caught?

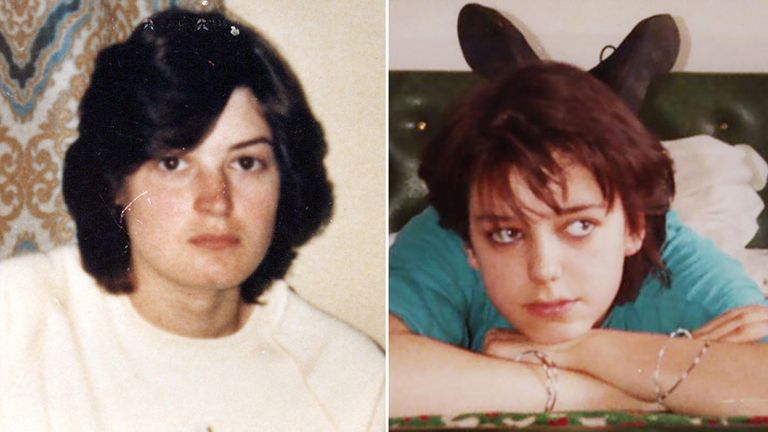

The murders of Wendy Knell and Caroline Pierce – known as “the bedsit murders” – had remained unsolved despite a DNA sample taken from Wendy’s body being enhanced by forensic scientists in 1999.

In 2019, a reinvestigation was boosted by an enhanced DNA sample from Caroline’s tights, but the breakthrough came from a sample from Wendy’s body.

Checks on a national database showed a close match to 90 people – which police detectives were able to whittle down, eventually identifying a relative of Fuller, before finding Fuller himself.

When police called on him at his home in Heathfield, East Sussex, he denied knowing the two women, but he was arrested and his DNA matched the killer’s. His fingerprint matched one in blood on a plastic bag found in Wendy’s bedsit.

It was during a search of his house and home office that detectives found hidden computer hard drives, CDs, and floppy discs with more than 14 million images of sex offences.

They included footage of Fuller sexually assaulting dead bodies in the morgue at the now-closed Kent and Sussex Hospital and the new 500-bed Tunbridge Wells Hospital in Pembury, which replaced it in 2011.

A number of hard drives were found attached to the back of a chest of drawers and officers found handwritten diaries in which Fuller had written details of his hospital victims – who ranged from a girl aged nine to a 100-year-old woman.

He initially denied murder charges, but on Thursday changed his pleas to guilty.

When asked why he had recorded and kept the images – and if it was for further sexual pleasure – he told detectives: “No,” adding later: “I don’t know why.”

He said the offences only took place within the hospital setting, but did not give any details about how or why he selected his victims.

How did he get away with it for so long?

Fuller, who worked as a maintenance supervisor, may have had legitimate reasons to visit the morgue – such as checking the temperature fridges – and so was given his own all-access swipe card to afford him entry.

The court was told: “CCTV from the mortuary area shows that when on cameras he carried items or performed actions that would afford a legitimate explanation for his presence.”

The mortuary had five members of staff who tended to work from 8am to 4pm. As Fuller generally worked from 11am to 7pm, his attacks often took place in the three-hour window at the latter part of his shift.

Although hospital porters could have come down to the mortuary with new bodies at any time, Fuller realised that no one came into the separate post-mortem room out of hours and the fridges in the centre of the morgue opened out into both rooms.

Fuller was able to enter the post-mortem room through the clinical office. The configuration of rooms meant he could get in and leave unnoticed by any porter who happened to enter the mortuary on the other side of the fridges while he was there.

Unlike other parts of the mortuary, there was no CCTV in the post-mortem room – a usual practice to preserve the dignity of patients.

However, this was exploited by Fuller who could open the fridge doors to access bodies because, while they were locked in the receiving area, they were unlocked in the post-mortem room.

Although CCTV cameras covered other areas, including the corridors leading to the mortuary these, and the swipe card system logs, were not checked to see if any member of staff was making an unusual number of journeys.

The stored images found by detectives only go back as far as 2008, but Fuller had worked at the hospital since 1989 so detectives believe there could be hundreds more victims.

More than 150 specialist family liaison officers have been tasked with visiting the victims’ families from Kent, Sussex and Essex.

Investigators have so far detected 99 potential victims, of which they know the names of 78.

However, it is feared some will never be identified.

Source: Read Full Article