Home » Australasia »

Why politics is toxic for Australia’s women

Australian women in politics have had enough.

A slew of allegations of sexist bullying and misogyny have emerged in recent years, while at the same time the country has steadily tumbled down the global rankings for female political representation.

Australia has tended to favour “larrikin” and “aggressor” MPs who thrive in the “rough-and-tumble” atmosphere of Canberra. But women MPs are increasingly saying that’s a culture in dire need of change.

As the country prepares to go to the polls on Saturday, the BBC looks at what’s come to be known as the “women problem” in Australian politics.

Sarah Hanson-Young was 25 when she won a seat in Australia’s Senate in 2007, the youngest woman ever to do so.

The Greens member has always been a forthright voice on progressive issues and women’s rights, but she has spoken extensively about how this was against a backdrop of mutterings from male opponents “about my dress, my body, and my supposed sex life”.

She had largely ignored them, choosing the well-trodden path of rising above it all. But an exchange in parliament last year proved the final straw.

It happened during a debate on women’s safety following a murder which shocked the nation. A young comedian walking home late at night had been killed by a stranger.

Ms Hanson-Young said women wouldn’t need extra protection if men didn’t rape them.

In response, an older male senator called out: “You should stop shagging men, Sarah.”

Liberal Democrat Senator David Leyonhjelm – known for revelling in his controversial remarks – refused to apologise when confronted by Ms Hanson-Young, who is divorced with a child. He instead repeated his comments and other explicit claims in TV and radio interviews.

He accused her of hypocrisy. She accused him of “slut-shaming” – where slurs about a women’s alleged sexual activities are used to demean or silence her.

Ms Hanson-Young said her 11-year-old daughter was asked at school whether her mum had “lots of boyfriends”.

“I decided at that moment I’d had enough of men in that place using sexism and sexist slurs, sexual innuendo as part of their intimidation and bullying on the floor of the parliament,” the senator said in a later interview.

She is suing Mr Leyonhjelm for defamation, on the grounds that he had attacked her character by suggesting she was a hypocrite and a misandrist (man-hater), and by repeatedly accusing her of making the claim that all men were rapists. Mr Leyonhjelm has consistently denied defaming her.

Ms Hanson-Young says she took the action because she is in a powerful enough position to do so whereas many women who encounter such comments at work are not.

“If we can’t clean it up in our nation’s parliament, well, where can we do it?”

‘Suffered in silence for too long’

Australian politics is known to be rambunctious, with plain speaking considered a national trait.

But female lawmakers say the comments and treatment they receive can often be explicitly gendered in nature, can border on abuse or intimidation and do not happen to their male counterparts.

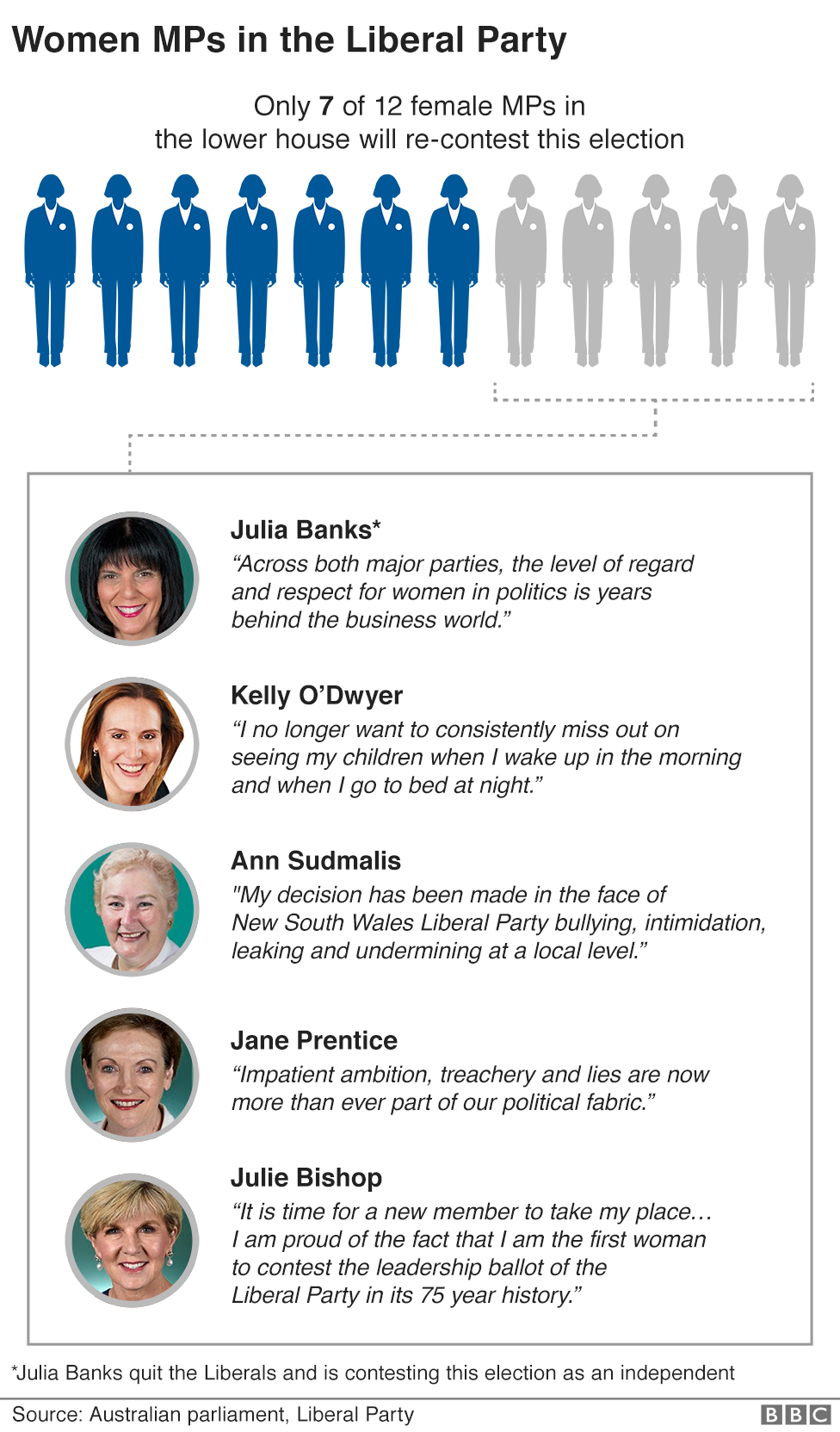

When one woman sensationally quit the ruling Liberal-led government last year, she sparked something of a groundswell revolt.

Australia, a hotspot of political coups, had just witnessed Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s ousting by party rivals. Julia Banks felt she had to act after experiencing the vicious infighting.

She pointed the finger at the “scourge of cultural and gender bias, bullying and intimidation” saying: “Women have suffered in silence for too long.”

She was later backed up by other women in the government, including the party’s deputy Julie Bishop who described “appalling” behaviour. One female senator threatened to name bullies, while the Minister for Women Kelly O’Dwyer confirmed allegations of bullying and intimidation.

The Liberal women have scotched suggestions that they’re just not up to the “rough-and-tumble” of politics, as one of their male colleagues put it.

“The hallmark characteristics of the Australian woman… are resilience and a strong authentic independent spirit,” blazed Ms Banks as she moved to the crossbench.

For her, it’s proof that it’s time for parliamentary culture to change. And that the only way to do that is “equal representation of men and women in this parliament”.

Representation fight

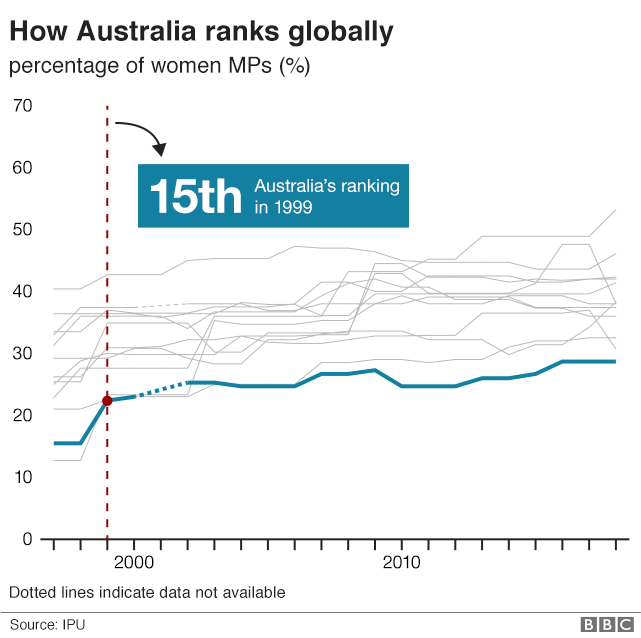

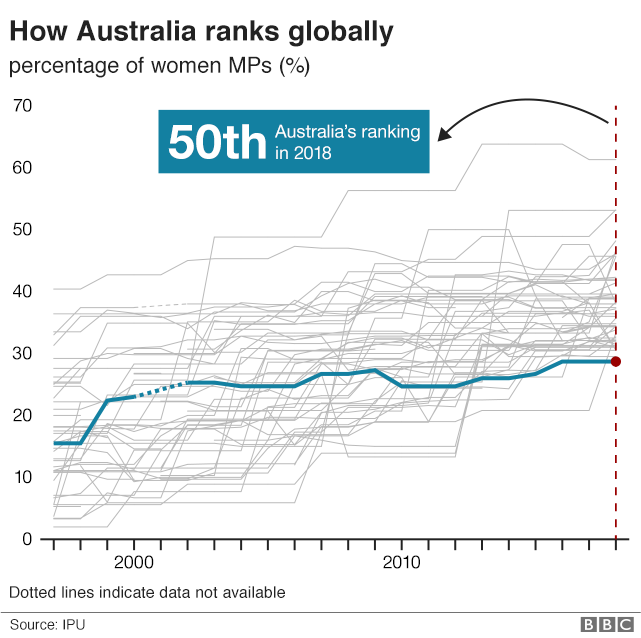

When it comes to gender diversity, Australia’s parliament is flagging.

Women – crucially, excluding indigenous Australians and most women of colour – first won the right to run in federal elections in 1902. But it took four decades – and 29 other countries do it first – before Australian women would actually win seats.

Female representation in Australia's parliament

Percentage of women in each chamber

They have always won more in the Senate because, say experts, it uses proportional voting by state – whereas the lower house has distinct electorates.

The current parliament has reached an all-time high for percentage of women MPs.

But when it comes to its international standing, Australia has fallen behind. In the past 20 years it’s slumped from 15th in the world to 50th for parliamentary gender diversity.

Overall, that’s partly due to a lack of pressure on both parties, says Dr Jill Sheppard, a political scientist at the Australian National University.

A recent Australian Broadcasting Corporation survey found significant support among women – though not men – for measures to improve the deficit.

Labor has such a mechanism. It introduced an affirmative action quota in 1994 and is now close to 50% representation – about double the proportion of women in the government. At Saturday’s election, women will contest 31% of its safe seats, according to election analyst Ben Raue.

The Liberal-National coalition may even see a dip in female representation, some analysts say. The coalition has put up women in only 16% of its safe seats, Mr Raue says.

“The Liberal Party is the drag here,” says Dr Sheppard, when asked about the nation’s fall in global diversity rankings.

She says the party tends to view its successful women “as almost unicorns – tremendous women who can’t be replicated”.

The party is seeking parity by 2025, but it is ideologically resistant to the idea of mandatory quotas and wants change to happen more organically.

“We don’t want to see women rise only on the basis of others doing worse,” said party leader and Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, in a speech on International Women’s Day.

He drew considerable criticism for the remarks, which were seen as implying men shouldn’t lose out to allow women to move up.

Targeted at the top

This is not a new issue for women in Canberra.

Natasha Stott Despoja joined parliament in 1995 at age 26, when women made up just 14% of the room.

In her 13 years as a senator, during which she became leader of the Australian Democrats, sexism was “endemic” in the political culture, she says.

“It ranged from male senators saying to me ‘you really should wear skirts’ to another senator referring to me only as ‘mother’ once I had children,” she told the BBC.

After leaving parliament, she went on to be Australia’s representative advancing women’s rights around the world. She observed other nations’ progress while watching the harassment continue at home.

“The single biggest disappointment for me has been the slow pace of change,” she says.

Many thought Australia had turned a corner when Julia Gillard became the first female prime minister in 2010.

Ms Gillard achieved many reforms in a tough three years of minority government. But her seizure of the top job – ousting Kevin Rudd in a party coup – haunted her reputation and public legitimacy.

Opponents and some media regularly portrayed her as a Lady Macbeth figure – a characterisation that invokes latent fears about ambitious women. Debate over policies like a contentious carbon tax often degenerated into personal and gendered attacks.

She was “routinely demonised” for being unmarried and “childless” in office, say Associate Prof Cheryl Collier from the University of Windsor and Associate Prof Tracey Raney from Ryerson University, both in Canada.

Such terms “are rarely if ever used to describe male heads of state”, they say in a 2018 report which compared the treatment of women MPs in Australia, UK and Canada.

Throughout her time in power the prime minister was called by her critics and opponents:

The fixation with her appearance at times was unashamedly lewd – a Liberal party fundraising dinner included a “Julia Gillard” menu item with explicit references to parts of her body. It also descended into violent imagery – one TV commentator said Australians “ought to be out there kicking her to death”. Another high-profile radio host said she should be “put into a chaff bag and thrown into the sea”.

The academics suggest the vitriol was so intense because Ms Gillard challenged the Australian stereotype of a good leader.

“Even women who have reached the top of the political ladder are working within an institution that privileges masculinity,” say Prof Collier and Prof Raney.

In 2012, Ms Gillard confronted the sexist, misogynistic attacks in a searing speech in parliament. It reverberated around the world, and to this day girls in Young Labor can quote it like a chant.

But in her final speech as prime minister, after she had been removed by her party, she was stoic about the impact her gender had had on her time in office.

“It doesn’t explain everything, it doesn’t explain nothing, it explains some things. And it is for the nation to think in a sophisticated way about those shades of grey.”

Leadership ideals

So is the problem just how things are done in parliament, or is it a wider issue about Australian culture?

It’s telling that the most senior female politicians in the past decade – Ms Gillard from Labor and Julie Bishop, a former Liberal deputy – do not have children.

In a country the size of Australia, parliamentary life for MPs based far from Canberra is especially taxing on families, a challenge which tends to be particularly hard for women to overcome.

In the past year, several MPs – including Ms O’Dwyer but also a male MP – left parliament saying the job was incompatible with family life.

But Dr Sonia Palmieri, a gender politics researcher at the 50/50 by 2030 Foundation – which wants to “achieve gender parity in leadership” – says unacknowledged bias remains the fundamental problem.

“Our system always seems to assume that our political actors are gender neutral – when in fact they revolve around standards which are masculine and of course that excludes and shuts out women,” she says.

Dr Palmieri argues this is partly because of specific notions of good political leadership in Australia.

She suggests there are roughly two types of accepted leader styles.

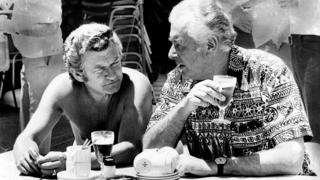

The first is the idea of the “larrikin” politician, a unique Australian term for a boisterous person – usually a man – whose bad behaviour is excused as disregard for convention.

Larrikins are seen as endearing in Australian culture, argues Dr Palmieri. There remains a cultural fascination with leaders such Prime Minister Bob Hawke – who could famously down a beer in seconds, and joked that the nation’s workers deserved a day off after a landmark sporting victory.

The second accepted leader is the aggressor – the acerbic politician revered for their ability to cut down the other side in parliamentary debate.

Prime ministers such as Paul Keating and Tony Abbott were noted for their attacking rhetoric in parliamentary debates although their styles widely differed.

Larrikins and aggro fit within the wider stereotypes of Australian identity, says political researcher Blair Williams from the Australian National University.

“We have these models of football players, surf lifesavers, that sort of blokey masculinity that someone like Tony Abbott definitely displayed. But it leaves women out.”

Aggression and even ambition are seen as unbecoming in women, says Dr Palmieri.

She too points to Ms Gillard, who was not only attacked for how she attained power – despite previous male leaders having seized control that way – but then wasn’t given the opportunity to show a different model of leadership to the public.

Some have also pointed out double standards in the treatment of Emma Husar, a Labor MP forced to resign last year after a news story made a salacious sexual harassment claim.

The report broke mistreatment claims, but focused on the MP’s sex life.

Ms Husar, a single mother, later said the “slut-shaming smears” ended her career. Her party asked her to step down less than two days after the report, she said.

A subsequent Labor investigation found no evidence of sexual harassment, but said “complaints that staff were subjected to unreasonable management… have merit”.

More on Australia’s election:

Dr Sheppard says both major parties are held back by traditional assumptions about women.

Party organisers fast-track men to office while “throwing obstacles in the path of women candidates”, she says.

“They’re not doing it deliberately, rather they’re acting on decades of ingrained behaviour and what they’re used to.” Men are just seen as the safer option.

However, her research shows that women are very electable. Her survey of more than 2,000 Australians in 2018 found that when other markers were equal, women candidates were actually more popular than men.

She refers to Scandinavian countries when she suggests that women in politics will become normalised once levels reach 30-40%. This is already the case for Labor, she says, while the Liberal party “has another 20 years to go”.

“We’re not there yet, but what we are seeing in Australia is quite rapid generational shift.

“I hope in 15 to 20 years, it won’t even be talked about as an issue.”

‘You need to be a bit brave’

Does this give hope to young women aspiring to enter politics?

In her school years Megan Stevens, 19 harboured ambitions of a career in parliament and is now studying politics at the University of Melbourne.

But increasingly she feels that she would be “more comfortable” working behind the scenes as a political staffer.

“How they treated Julia Gillard really put me off,” she says.

The same goes for Liliana Tai, the University of Sydney student union president and a debating champion who interned at parliament over the summer.

She says pursuing a career in “real” politics is an almost overwhelming prospect.

Ms Tai fears that the cultural change needed to allow someone like her, a young, Chinese-Australian woman, to become an elected representative “may not be achieved in our lifetime”.

“People think of leaders as what they’re familiar with and what they know and historically that’s been predominantly male, predominantly Anglo people,” she says.

She believes that both parties still cater towards stereotypes in selecting candidates.

“I think they fixate so much on electability that they prioritise what they think people want and that leads to a pernicious cycle of not having change.”

“But you need to be a bit brave, and go out on a limb and give that new person a chance.”

Last year, the failed leadership bid by the government’s most powerful woman, Julie Bishop, proved to Ms Tai that merit isn’t enough.

Ms Bishop was deputy to four successive male party leaders over 11 years. An MP for two decades, she also served as Australia’s first female foreign minister.

But she resigned from the front bench last year after losing a leadership battle to Scott Morrison. Her prospects were dashed by colleagues who tactically voted to keep another man out.

The Australian Financial Review called her: “The female Prime Minister who never was”.

On the day of her resignation, she wore scarlet heels.

Whatever the politics of the events, a photograph of the lavish shoes, amid a sea of brogues and dark suits, became an iconic image of a lone woman cut out of power.

Australia’s Museum of Democracy later exhibited the shoes, along with the photo, which they said were “a bold statement and a symbol of solidarity and empowerment among Australian women”.

Ms Tai says she also took some hope from Ms Bishop’s departure.

She mentions her final parliamentary speech, where the outgoing MP said public office was “one of the highest callings”.

“I really resonated with that because that’s what I believe too,” says Ms Tai.

“Being in parliament is still the best way to represent people and bring about change.”

Edited by Jay Savage and Anna Jones

Source: Read Full Article