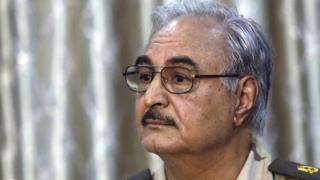

Profile: Libya’s military strongman Khalifa Haftar

Khalifa Haftar has been part of the Libyan political scene for more than four decades, shifting from the centre to the periphery and back again as his fortunes changed.

Forces under his command have seized control of Libya’s main oil terminals, handing the key to the country’s crucial oil exports to his ally – the elected parliament based in the eastern city of Tobruk.

Born in 1943 in the eastern town of Ajadbiya, Haftar was one of the group of officers led by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi which seized power from King Idris in 1969.

Downfall and exile

Gaddafi put Haftar – recently promoted to field marshal – in charge of the Libyan forces involved in the conflict in Chad in the 1980s. This proved to be his downfall, as Libya was defeated by the French-backed Chadian forces, and Haftar and 300 of his men were captured by the Chadians in 1987.

Having previously denied the presence of Libyan troops in the country, Gaddafi disowned him. This led Haftar to devote the next two decades towards toppling the Libyan leader.

He did this from exile in the US state of Virginia. His proximity to the CIA’s headquarters in Langley hinted at a close relationship with US intelligence services, who gave their backing to several attempts to assassinate Gaddafi.

Return from exile

After the start of the uprising against Gaddafi in 2011, Haftar returned to Libya where he became a key commander of the makeshift rebel force in the east.

With Gaddafi’s downfall, Haftar faded into obscurity until February 2014, when he outlined on TV his plan to save the nation and called on Libyans to rise up against the elected parliament, the General National Congress (GNC), whose mandate was still valid at the time.

His dramatic announcement was made at a time when Libya’s second city, Benghazi, and other towns in the east had in effect been taken over by the local al-Qaeda affiliate, Ansar al-Sharia, and other Islamist groups who mounted a campaign of assassinations and bombings targeting the military, police personnel and other public servants.

Although Haftar did not have the wherewithal to put his plan into action, his announcement reflected popular sentiment, especially in Benghazi, which had become disenchanted with the total failure of the GNC and its government to confront the Islamists.

Haftar’s popularity is not necessarily shared elsewhere in the country where he is remembered more for his past association with Gaddafi and his subsequent US connections.

He is also detested by Islamists who resent him for confronting them in Benghazi and elsewhere in the east.

Operation Dignity

In May 2014 Haftar launched Operation Dignity against Islamist militants in Benghazi and the east. In March 2015 Libya’s elected parliament, the House of Representatives (HoR) – which had replaced the GNC – appointed him commander of the Libyan National Army (LNA).

After a year of little progress, in February 2016 the LNA pushed the Islamist militants out of much of Benghazi. By mid-April this had been followed up by further military action that dislodged the Islamists from their strongholds outside Benghazi and as far as Derna, 250km east of Benghazi.

Operation Swift Thunder

In September 2016, the LNA launched operation “Swift Thunder”, seizing from the Petroleum Facilities Guard – an armed group aligned with the UN-brokered Government of National Accord (GNA) – the key oil terminals of Zueitina, Brega, Ras Lanuf and Sidrah, in the oil-rich heartland locally known as the Oil Cresent.

In recognition of this, the Speaker of the HoR and supreme commander of the armed forces, Agilah Saleh, promoted Haftar from lieutenant-general to field marshal.

Problem or solution?

Haftar is reported to be unhappy with the line-up of the GNA, which has allocated the defence portfolio to another officer, Ibrahim al-Barghathi. And he is suspicious of the GNA’s reliance on the mainly Misrata-based militias, which include some Islamist elements.

The Skhirat agreement of December 2015, which laid the foundation for the national unity government, stipulated that the HoR meet within one month of the proposed unity government to consider whether to grant it a vote of confidence.

However, after several attempts the HoR, has failed to attain the necessary quorum to vote on the proposed cabinet.

According to media reports, proponents of the unity government within the HoR blame this on Haftar, who is said to have persuaded his supporters among the deputies to deprive the legislature of the necessary number of attendants.

Haftar insists that he will abide by any decision taken by the HoR.

While he has been ambiguous about his own political ambition, it is likely that this is confined to a key role for himself in the new army under the national unity government and, more generally, for the LNA in the new armed forces.

Why is Libya so lawless?

The fight against IS

BBC Monitoring reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter and Facebook.

Source: Read Full Article