Home » World News »

COVID-19: Should we be worried about coronavirus mutating – and could it affect the vaccine?

A new variant of COVID-19 in the UK is believed to be behind the faster spread of infections in South East England – but it is not the first time the virus had mutated since the start of the pandemic.

In fact, it may not even the first time a mutation – or a change in the virus’ genetic material – has altered how infectious it is.

Should we be worried?

Mutations – although scarily named – are not necessarily a bad thing.

Every virus mutates because, when it makes contact with a host, it makes new copies of itself that can infect other cells.

RNA viruses such as coronavirus are more prone to slight changes happening as the copies are made.

In some cases, a mutation may even make the virus weaker. But in others, they could make the virus more infectious or cause more serious illness.

COVID-19 has been mutating every week or so, with many of the mutations having no impact on the virus.

This latest mutation found in the UK appears to help the virus spread faster, but there is no indication yet it has made it more deadly or that it could evade a vaccine.

Sky’s science correspondent Thomas Moore has said the mutation is “not wholly unusual” but “it is something that they will be keeping a very close watch on”.

What are the different strains?

So far, there have been at least seven major groups, or strains, of COVID-19 as it adapts to its human hosts.

The original strain, discovered in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December last year, is known as the L strain.

It then mutated into the S strain at the beginning of 2020, before being followed by the V and G strains.

Strain G has been most commonly found in Europe and North America – but because these continents were slow to restrict movement, it allowed the virus to spread faster and therefore mutate further into strains GR, GH and GV.

Meanwhile, the original L strain persisted for longer in Asia because several countries – including China – were quick to shut their borders and stop movement.

Several other less frequent mutations are grouped together as strain O.

What are the most common strains around the world?

G strains are now dominant around the world, particularly in Italy and Europe, coinciding with spikes in outbreaks.

A specific mutation, D614G, is the most common variant. Some experts say this variation has made the virus more infectious, but other studies have contradicted this.

Meanwhile, earlier strains such as the original L strain and the V strain are gradually disappearing.

Analysis by the Reuters news agency shows that Australia’s quick reaction to the pandemic and effective social distancing measures have eliminated transmission of the earlier L and S strains in the country, and that new infections are the result of G strains brought in from overseas.

In Asia, the strains G, GH and GR have been increasing since the beginning of March, more than a month after they started spreading in Europe.

Will mutations affect the vaccine?

So far, experts have not found any variants that could make a vaccine less effective, and the virus has been slow to mutate.

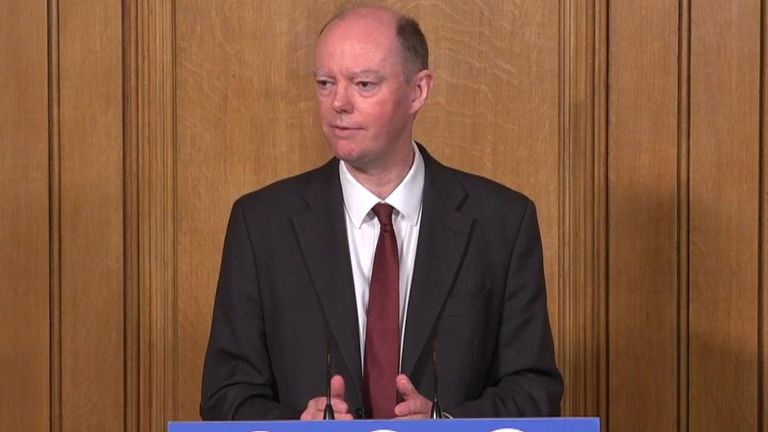

Reacting to the new strain found in the UK, England’s chief medical officer Professor Chris Whitty said it would be “surprising” if it had an effect on the vaccine, although added there should be more hard data relatively soon.

Federico Giorgi, a researcher at the University of Bologna and who co-ordinated a study into strains of COVID-19, told Science Daily: “The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is presumably already optimised to affect human beings, and this explains its low evolutionary change.

“This means that the treatments we are developing, including a vaccine, might be effective against all the virus strains.”

A group of scientists from several institutions including the University of Sheffield and Harvard University have also suggested G strains could make a better target for a vaccine because these strains have more spike proteins on their surface.

However, University College of London Genetics Institute researcher Lucy van Dorp said we should still remain “vigilant” and continue to monitor any new mutations.

The best way of ensuring the virus does not evade a vaccine is to stop infections spreading and reducing the chances of it mutating.

Catherine Bennett, epidemiology chair in the faculty of health at Melbourne’s Deakin University, said: “If the virus changes substantially, particularly the spike proteins, then it might escape a vaccine. We want to slow transmission globally to slow the clock.

“That reduces the chances of a one in a squillion change that’s awful news for us.”

Source: Read Full Article