Home » World News »

Coronavirus: ‘COVID-19 only takes white people’: Researchers battle disease myths in South Africa

As the coronavirus clings on, reasserting itself in countries like UK and the United States, the hopes and fears of politicians, scientists and the rest of humanity centre on a relatively small number of vaccines currently in development.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there are 182 vaccines being worked on but only nine are currently being evaluated in final “phase three” human trials.

A return to something like pre-outbreak normality now rests on a batch of these late-stage vaccines being proven effective.

In South Africa, three of the most promising vaccines are being tested in cities throughout the country, with 2,000 participants trialling an inoculation developed by Oxford University’s Jenner Institute.

The study was recently paused after one person in the UK fell ill, but the trial has resumed with participants at Johannesburg’s giant Baragwanath Hospital receiving the second part of this two-dose vaccine this week.

“Do you think this vaccine could work?” I asked Bonginkosi Ntombela, who lives in the township of Soweto.

“I hope it works, we have to cure this disease,” he replied. “It is taking so many of our people, young, old, black, white.”

The man in charge of the Oxford trial, as well as a second COVID-19 vaccine from US firm Novamax, is called Professor Shabir Madhi and we found him scuttling between a series of laboratories at the Baragwanath complex.

Mounting his own worldwide marketing campaign, the University of Witswaterand professor has personally convinced vaccine developers to undertake clinical trials in South Africa and secured millions of pounds in funding to make the enterprise happen.

“What we need to understand is that there is no rush on the part of pharmaceutical companies to do studies in Africa.

“None at all. There is very little incentive for them to come here. The only reason (the Oxford trial) is being done in South Africa is that I went out to convince people that you need to do it now… and you can’t wait to do it after the pandemic has passed.”

Professor Madhi invokes the memory of infections like swine flu when making the case for vaccine trials in Africa. Little research was conducted on this respiratory disease when it emerged in 2009 and by the time a usable vaccine was produced in Africa the pandemic was effectively over. The same mistake must not be repeated, he says.

“It would be a crime against humanity, a crime against the people of Africa if the mechanism was not put into place to introduce vaccines during the time of pandemic and not after it has passed – especially if we can show that the vaccines actually work.”

However, the battle against the virus will not be waged solely in the laboratory. Social scientists from the University of Witswaterand are asking whether members of the public whether they will take an effective COVID-19 vaccine.

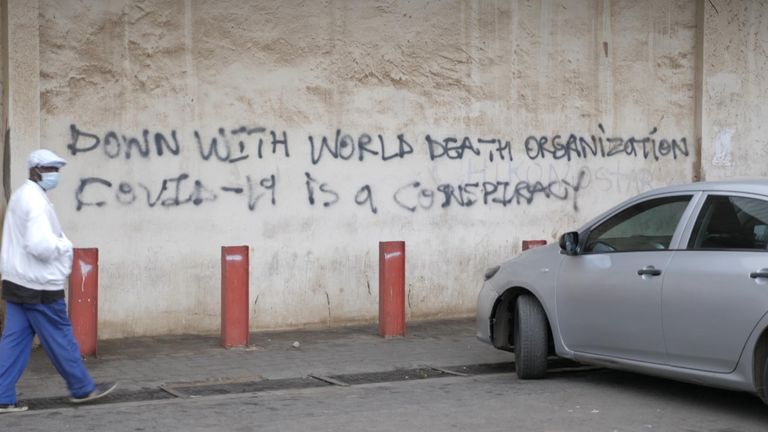

In South Africa alone, there are a multitude of myths and misconceptions about the virus which are routinely advanced on the streets and social media.

One such theory was laid out at the clinic at Baragwanath Hospital by a 19-year-old student called Shantel Manganye.

Explaining why her friends and neighbours would refuse a COVID-19 vaccine, she said there is a common view that the virus selects its prey.

“To be honest we have this mindset that this illness is only taking white people and stuff… they are trying to say this disease can see, it can feel, if you have money then it attacks you. If you are poor it cannot come because it knows that you don’t have money.”

Researcher Noni Mgwenya, from the University of Witswaterand, says such stories are created in an effort to make sense of something that is poorly understood.

“They feel that it is not real, that whoever invented (the virus) brought it here to kill South Africans… (people) think things have been put in to reduce the population in Africa.”

:: Subscribe to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Deep levels of scepticism and mistrust aimed at COVID-19 vaccine development are not unique to South Africa. They are a part of a global phenomenon, powered in part by amateur theorists on social media.

Challenging it through community education campaigns may become as important as the introduction of the vaccines themselves.

Source: Read Full Article