Brexit: History can teach Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn a lot about compromise

The prime minister and the opposition leader have resorted to working with each other in a bid to move forward with Brexit.

But what lessons can Theresa May and Jeremy Corbyn learn from the UK’s political past?

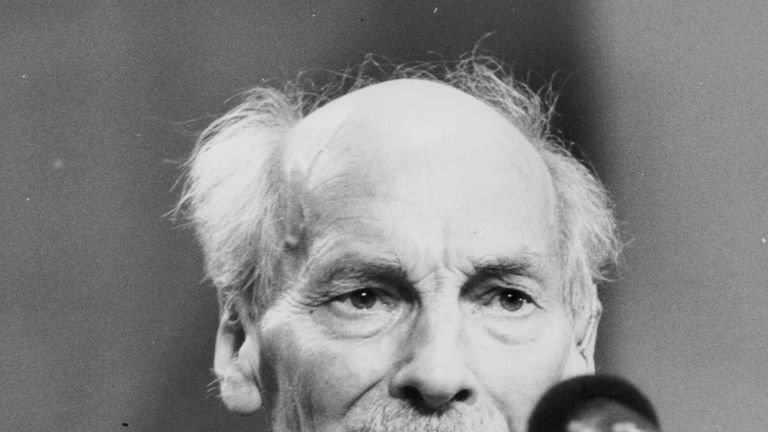

Here, David Cohen, the author of Churchill and Attlee: The Unlikely Allies Who Won The War, gives Sky News an insight into old political tensions.

He has a PhD in psychology and his films include the BAFTA-nominated When Holly Went Missing (ITV) about the Soham murders.

Prime Minister Theresa May and Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn can learn a lot from history about how to deal with Brexit.

But first they have to admit that they have so far been unwilling to compromise much – politically and psychologically. And they have to change that.

In the last century, governments of national unity were formed when Britain was at war and once in 1931, when there was financial panic and a run on the pound.

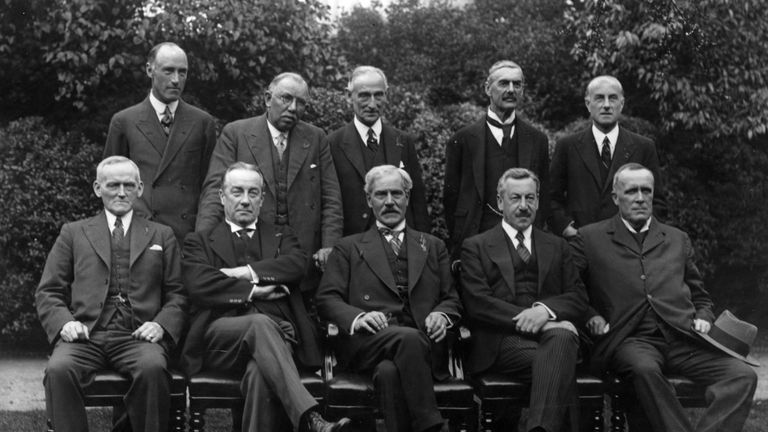

The leaders in those dramatic moments were Herbert Asquith, David Lloyd George, Stanley Baldwin, Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee and Baldwin (again).

In a poll of leading historians carried out some 10 years ago, Mr Attlee, Mr Churchill and Mr Lloyd George were reckoned to be the best prime ministers of the century. Mr Asquith and Mr Baldwin came seventh and eighth. It would be cruel to compare our current politicians to any of them.

But it may help to offer our leaders a brief history of how to achieve compromise with an opponent.

On 24 August 1931, the Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald sprang a surprise, telling his cabinet he intended to form a national unity government with the Conservatives and Liberals. The dire economics demanded it.

At that meeting Mr Attlee said, making sure that Mr MacDonald was within earshot, that “Esau sold his inheritance for a few pieces of silver”.

Mr Attlee would have nothing to do with the unity plan. He wrote to his brother Tom, telling him that “things are pretty damnable – I fear we are in for a regime of fake economy and a general attack on the workers’ standard of life”.

Mr Churchill found the moment damnable, too. Though he had been home secretary and chancellor, Mr MacDonald did not offer him a post in the new national government.

Mr Attlee described the 1931 election that followed Mr MacDonald’s decision as the most “unscrupulous” he could remember. Mr Attlee just managed to cling on to his seat. Mr Churchill said the triumph of the national government made him fear for British democracy.

The national government did not solve Britain’s economic problems, but Mr Attlee and Mr Churchill learned something by rejecting and being rejected.

When Mr Chamberlain was forced out in 1940, they formed a government that won the war. They worked well together because both men were ready to share a drink and compromise without much fuss. They appointed key ministers in two days.

The much derided Mr Chamberlain got into the spirit of compromise and drafted proposals on organising the war time economy, proposals Mr Attlee got through the House in one day. Yet Mr Attlee hated Mr Chamberlain. They all put personal ambition and personal obsessions aside.

You do not become prime minister or leader of the opposition if you have no qualities but history suggests – sorry to sound like a life coach – both Mrs May and Mr Corbyn now need to find their better selves.

Source: Read Full Article