Home » Middle East »

The rise and fall of ‘Islamic State’

Abu Anis only realised something unusual was happening when he heard the sound of explosions coming from the old city on the western bank of the Tigris as it runs through Mosul.

“I phoned some friends over there, and they said armed groups had taken over, some of them foreign, some Iraqis,” the computer technician said. “The gunmen told them, ‘We’ve come to get rid of the Iraqi army, and to help you.'”

The following day, the attackers crossed the river and took the other half of the city. The Iraqi army and police, who vastly outnumbered their assailants, broke and fled, officers first, many of the soldiers stripping off their uniforms as they joined a flood of panicked civilians.

It was 10 June 2014, and Iraq’s second biggest city, with a population of around two million, had just fallen to the militants of the group then calling itself Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham/the Levant (Isis or Isil).

Four days earlier, black banners streaming, a few hundred of the Sunni militants had crossed the desert border in a cavalcade from their bases in eastern Syria and met little resistance as they moved towards their biggest prize.

Rich dividends were immediate. The Iraqi army, rebuilt, trained and equipped by the Americans since the US-led invasion of 2003, abandoned large quantities of armoured vehicles and advanced weaponry, eagerly seized by the militants. They also reportedly grabbed something like $500m from the Central Bank’s Mosul branch.

“At the beginning, they behaved well,” said Abu Anis. “They took down all the barricades the army had put up between quarters. People liked that. On their checkpoints they were friendly and helpful – ‘Anything you need, we’re here for you.'”

The Mosul honeymoon was to last a few weeks. But just down the road, terrible things were already happening.

As the Iraqi army collapsed throughout the north, the militants moved swiftly down the Tigris river valley. Towns and villages fell like skittles. Within a day they had captured the town of Baiji and its huge oil refinery, and moved on swiftly to seize Saddam Hussein’s old hometown, Tikrit, a Sunni hotbed.

Just outside Tikrit is a big military base, taken over by the Americans in 2003 and renamed Camp Speicher after the first US casualty in the 1991 “Desert Storm” Gulf war against Iraq, a pilot called Scott Speicher, shot down over al-Anbar province in the west.

Camp Speicher, by now full of Iraqi military recruits, was surrounded by the Isis militants and surrendered. The thousands of captives were sorted, the Shia were weeded out, bound, and trucked away to be systematically shot dead in prepared trenches. Around 1,700 are believed to have been massacred in cold blood. The mass graves are still being exhumed.

Far from trying to cover up the atrocity, Isis revelled in it, posting on the internet videos and pictures showing the Shia prisoners being taken away and shot by the black-clad militants.

In terms of exultant cruelty and brutality, worse was not long in coming.

After a pause of just two months, Isis – now rebranded as “Islamic State” (IS) – erupted again, taking over large areas of northern Iraq controlled by the Kurds.

That included the town of Sinjar, mainly populated by the Yazidis, an ancient religious minority regarded by IS as heretics.

Hundreds of Yazidi men who failed to escape were simply killed. Women and children were separated and taken away as war booty, to be sold and bartered as chattels, and used as sex slaves. Thousands are still missing, enduring that fate.

Deliberately shocking, bloodthirsty exhibitionism reached a climax towards the end of the same month, August 2014.

IS issued a video showing its notorious, London-accented and now late executioner Mohammed Emwazi (sardonically nicknamed “Jihadi John” by former captives) gruesomely beheading American journalist James Foley.

In the following weeks, more American and British journalists and aid workers – Steven Sotloff, David Haines, Alan Henning, and Peter Kassig (who had converted to Islam and changed his name to Abdul Rahman) – appeared being slaughtered in similar, slickly produced videos, replete with propaganda statements and dire warnings.

In the space of a few months, IS had blasted its way from obscurity on to the centre of the world stage. Almost overnight, it became a household word.

Seven-and-a-half thousand miles (12,000km) away, then Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott summed up the breathtaking novelty of the horror. It was, he said “medieval barbarism, perpetrated and spread with the most modern of technology”.

IS had arrived, and the world was taking notice. But the men in black did not appear out of the blue. They had been a long time coming.

The theology of murder

The ideological or religious roots of IS and like-minded groups go deep into history, almost to the beginning of Islam itself in the 7th Century AD.

Like Christianity six centuries before it, and Judaism some eight centuries before that, Islam was born into the harsh, tribal world of the Middle East.

“The original texts, the Old Testament and the Koran, reflected primitive tribal Jewish and Arab societies, and the codes they set forth were severe,” writes the historian and author William Polk.

“They aimed, in the Old Testament, at preserving and enhancing tribal cohesion and power and, in the Koran, at destroying the vestiges of pagan belief and practice. Neither early Judaism nor Islam allowed deviation. Both were authoritarian theocracies.”

As history moved on, Islam spread over a vast region, encountering and adjusting to numerous other societies, faiths and cultures. Inevitably in practice it mutated in different ways, often becoming more pragmatic and indulgent, often given second place to the demands of power and politics and temporal rulers.

For hardline Muslim traditionalists this amounted to deviationism, and from early on, there was a clash of ideas in which those arguing for a strict return to the “purity” of the early days of Islam often paid a price.

The eminent scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780-855), who founded one of the main schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence, was jailed and once flogged unconscious in a dispute with the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. Nearly five centuries later, another supreme theologian of the same strict orthodox school, Ibn Taymiyya, died in prison in Damascus.

These two men are seen as the spiritual forefathers of later thinkers and movements which became known as “salafist”, advocating a return to the ways of the first Muslim ancestors, the salaf al-salih (righteous ancestors).

They inspired a later figure whose thinking and writings were to have a huge and continuing impact on the region and on the salafist movement, one form of which, Wahhabism, took his name.

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab was born in 1703 in a small village in the Nejd region in the middle of the Arabian peninsula.

A devout Islamic scholar, he espoused and developed the most puritanical and strict version of what he saw as the original faith, and sought to spread it by entering pacts with the holders of political and military power.

In an early foray in that direction, his first action was to destroy the tomb of Zayd ibn al-Khattab, one of the Companions of the Prophet Muhammad, on the grounds that by the austere doctrine of salafist theology, the veneration of tombs constitutes shirk, the revering of something or someone other than Allah.

But it was in 1744 that Abd al-Wahhab made his crucial alliance with the local ruler, Muhammad ibn Saud. It was a pact whereby Wahhabism provided the spiritual or ideological dimension for Saudi political and military expansion, to the benefit of both.

Passing through several mutations, that dual alliance took over most of the peninsula and has endured to this day, with the House of Saud ruling in sometimes uneasy concert with an ultra-conservative Wahhabi religious establishment.

The entrenchment of Wahhabi salafism in Saudi Arabia – and the billions of petrodollars to which it gained access – provided one of the wellsprings for jihadist militancy in the region in modern times. Jihad means struggle on the path of Allah, which can mean many kinds of personal struggle, but more often is taken to mean waging holy war.

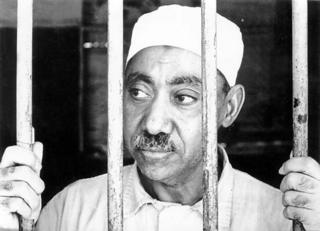

But the man most widely credited, or blamed, for bringing salafism into the 20th Century was the Egyptian thinker Sayyid Qutb. He provided a direct bridge from the thought and heritage of Abd al-Wahhab and his predecessors to a new generation of jihadist militants, leading up to al-Qaeda and all that was to follow.

Born in a small village in Upper Egypt in 1906, Sayyid Qutb found himself at odds with the way Islam was being taught and managed around him. Far from converting him to the ways of the West, a two-year study period in the US in the late 1940s left him disgusted at what he judged unbridled godless materialism and debauchery, and his fundamentalist Islamic outlook was honed harder.

Back in Egypt, he developed the view that the West was imposing its control directly or indirectly over the region in the wake of the Ottoman Empire’s collapse after World War One, with the collaboration of local rulers who might claim to be Muslims, but who had in fact deviated so far from the right path that they should no longer be considered such.

For Qutb, offensive jihad against both the West and its local agents was the only way for the Muslim world to redeem itself. In essence, this was a kind of takfir – branding another Muslim an apostate or kafir (infidel), making it justified and even obligatory and meritorious to kill him.

Although he was a theorist and intellectual rather than an active jihadist, Qutb was judged dangerously subversive by the Egyptian authorities. He was hanged in 1966 on charges of involvement in a Muslim Brotherhood plot to assassinate the nationalist President, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Qutb was before his time, but his ideas lived on in the 24 books he wrote, which have been read by tens of millions, and in the personal contact he had with the circles of people like Ayman al-Zawahiri, another Egyptian who is the current al-Qaeda leader.

Another intimate of the al-Qaeda founder Osama Bin Laden said: “Qutb was the one who most affected our generation.” He has also been described as “the source of all jihadist thought”, and “the philosopher of the Islamic revolution”.

More than 35 years after he was hanged, the official commission of inquiry into al-Qaeda’s 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers in 2001 concluded: “Bin Laden shares Qutb’s stark view, permitting him and his followers to rationalise even unprovoked mass murder as righteous defence of an embattled faith.”

And his influence lingers on today. Summing up the roots of IS and its predecessors, the Iraqi expert on Islamist movements Hisham al-Hashemi said: “They are founded on two things: a takfiri faith based on the writings of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, and as methodology, the way of Sayyid Qutb.”

The theology of militant jihadism was in place. But to flourish, it needed two things – a battlefield, and strategists to shape the battle.

Afghanistan was to provide the opportunity for both.

Rise of al-Qaeda

The Soviet invasion in 1979, and the 10 years of occupation that followed, provided a magnet for would-be jihadists from around the Arab world. Some 35,000 of them flocked to Afghanistan during that period, to join the jihad and help the mainly Islamist Afghan mujahideen guerrillas turn the country into Russia’s Vietnam.

There is little evidence that the “Afghan Arabs”, as they became known, played a pivotal combat role in driving the Soviets out. But they made a major contribution in setting up support networks in Pakistan, channelling funds from Saudi Arabia and other donors, and funding schools and militant training camps. It was a fantastic opportunity for networking and forging enduring relationships as well as tasting jihad first hand.

Ironically, they found themselves on the same team as the Americans. The CIA’s Operation Cyclone channelled hundreds of millions of dollars through Pakistan to militant Afghan mujahedeen leaders such as Golbuddin Hekmatyar, who associated closely with the Arab jihadists.

It was in Afghanistan that virtually all the major figures in the new jihadist world cut their teeth. They helped shape events there in the aftermath of the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, a period that saw the emergence of al-Qaeda as a vehicle for a wider global jihad, and Afghanistan provided a base for it.

By the time the Taliban took over in 1996, they were virtually in partnership with Osama Bin Laden and his men, and it was from there that al-Qaeda launched its fateful 9/11 attack in 2001.

The formative Afghan experience provided both the combat-hardened salafist jihadist leaders and the strategists who were to play an instrumental role in the emergence of the IS of today.

Most significant was the Jordanian jihadist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who more than anybody else ended up being the direct parent of IS in almost every way.

A high-school dropout whose prison career began with a sentence for drug and sexual offences, Zarqawi found religion after being sent to classes at a mosque in the Jordanian capital, Amman. He arrived in Pakistan to join jihad in Afghanistan just in time to see the Soviets withdraw in 1989, but stayed on to work with jihadists.

After a stint back in Jordan where he received a 15-year jail sentence on terrorist charges but was later released in a general amnesty, Zarqawi finally met Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri in 1999. By all accounts the two al-Qaeda leaders did not take to him. They found him brash and headstrong, and they did not like the many tattoos from his previous life that he had not been able to erase.

But he was charismatic and dynamic, and although he did not join al-Qaeda, they eventually put him in charge of a training camp in Herat, western Afghanistan. It was here that he worked with an ideologue whose radical writings became the scriptures governing subsequent salafist blood-letting: Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir.

“The brutality of beheading is intended, even delightful to God and His Prophet,” wrote Muhajir in his book The Theology of Jihad, more generally referred to as the Theology of Bloodshed. His writings provided religious cover for the most brutal excesses, and also for the killing of Shia as infidels, and their Sunni collaborators as apostates.

The other book that has been seen as the virtual manual – even the Mein Kampf – for IS and its forebears is The Management of Savagery, by Abu Bakr Naji, which appeared on the internet in 2004.

“We need to massacre and to do just as has been done to Banu Qurayza, so we must adopt a ruthless policy in which hostages are brutally and graphically murdered unless our demands are met,” Naji wrote. He was referring to a Jewish tribe in seventh-century Arabia which reportedly met the same fate at the hands of early Muslims as the Yazidis of Sinjar did nearly 14 centuries later: the men were slaughtered, the women and children enslaved.

Naji’s sanctioning of exemplary brutality was part of a much wider strategy to prepare the way for an Islamic caliphate. Based partly on the lessons of Afghanistan, his book is a detailed blueprint for provoking the West into interventions which would further rally the Muslims to jihad, leading to the ultimate collapse of the enemy.

The scenario is not so fanciful if you consider that the Soviet Union went to pieces barely two years after its withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Naji is reported to have been killed in a US drone strike in Pakistan’s Waziristan province in 2008.

Iraq fiasco

The fallout from the 9/11 attacks changed things radically for the jihadists in late 2001. The US and allies bombed and invaded Afghanistan, ousting the Taliban, and launching a wider “War on Terror” against al-Qaeda.

Bin Laden went underground, and Zarqawi and others fled. The dispersing militants, fired up, badly needed another battlefield on which to provoke and confront their Western enemies.

Luck was on their side. The Americans and their allies were not long in providing it.

Their invasion of Iraq in the spring of 2003 was, it turned out, entirely unjustified on its own chosen grounds – Saddam Hussein’s alleged production of weapons of mass destruction, and his supposed support for international terrorists, neither of which was true.

By breaking up every state and security structure and sending thousands of disgruntled Sunni soldiers and officials home, they created precisely the state of “savagery”, or violent chaos, that Abu Bakr Naji envisaged for the jihadists to thrive in.

Iraq was on the way to becoming what US officials came to call the “parent tumour” of the IS presence in the region.

Under Saddam’s tightly-controlled Baath Party regime, the Sunnis enjoyed pride of place over the majority Shia, who have strong ties with their co-religionists across the border in Iran.

The US-led intervention disempowered the Sunnis, creating massive resentment and providing fertile ground for the outside salafist jihadists to take root in.

They were not long in spotting their constituency. Abu Musab Zarqawi moved in, and within a matter of months was organising deadly, brutal and provocative attacks aimed both at Western targets and at the majority Shia community.

Doctrinal differences between the two sects go back to disputes over the succession to the Prophet Muhammad in the early decades of Islam, but conflict between them is generally based on community, history and sectarian politics rather than religion as such.

Setting himself up with a new group called Tawhid wa al-Jihad (Tawhid means declaring the uniqueness of Allah), Zarqawi immediately forged a pragmatic operational alliance with underground cells of the remnants of Saddam’s regime, providing the two main intertwined strands of the Sunni-based insurgency: militant Jihadism, and Iraqi Sunni nationalism with Baathist organisation at its core.

His group claimed responsibility for several deadly attacks in August 2003 that set the pattern for much of what was to come: a suicide truck bomb explosion at the UN headquarters in Baghdad that killed the envoy Sergio Vieira de Mello and 20 of his staff, and a suicide car bomb blast in Najaf which killed the influential Shia ayatollah Muhammad Baqir al-Hakim and 80 of his followers. The bombers were salafist jihadists, but logistics were reportedly provided by underground Baathists.

The following year, Zarqawi himself was believed by the CIA to be the masked killer shown in a video beheading an American hostage, Nicholas Berg, in revenge for the Abu Ghraib prison abuses of Iraqi detainees by members of the US military.

As the battle with the Americans and the new Shia-dominated Iraqi government intensified, Zarqawi finally took the oath of loyalty to Bin Laden, and his group became the official al-Qaeda branch in Iraq.

But they were never really on the same page. Zarqawi’s provocative attacks on Shia mosques and markets, triggering sectarian carnage, and his penchant for publicising graphic brutality, were all in line with the radical teachings he had imbibed. But they drew rebukes from the al-Qaeda leadership, concerned at the impact on Muslim opinion.

Zarqawi paid little heed. His strain of harsh radicalism passed to his successors after he was killed by a US air strike in June 2006 on his hideout north of Baghdad. He was easily identified by the tattoos he had never managed to get rid of.

The direct predecessor of IS emerged just a few months later, with the announcement of the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) as an umbrella bringing the al-Qaeda branch together with other insurgent factions.

But tough times lay ahead. In January 2007, the Americans began “surging” their own troops in Iraq from 132,000 to a peak of 168,000, adopting a much more hands-on approach in mentoring the rebuilt Iraqi army. At the same time, they enticed Sunni tribes in western al-Anbar province to stop supporting the jihadists and join the US-led Coalition-Iraqi government drive to quell the insurgency, which many did, on promises that they would be given jobs and control over their own security.

By the time both the new ISI and al-Qaeda leaders were killed in a US-Iraqi army raid on their hideout in April 2010, the insurgency was at its lowest ebb, pushed back into remote corners of Sunni Iraq.

They were both replaced by one man, about whom very little was publicly known at the time, and not much more since: Ibrahim Awad al-Badri, better known by his nom de guerre, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Six eventful years later, he would be proclaimed Caliph Ibrahim, Commander of the Faithful and leader of the newly declared “Islamic State”.

Territorial takeover

Baghdadi’s career is so shrouded in mist that there are very few elements of it that can be regarded as fact. By all accounts he was born near Samarra, north of Baghdad, so the epithet “Baghdadi” seems to have been adopted to give him a more national image, while “Abu Bakr” evokes the first successor to (and father-in-law of) Prophet Muhammad.

Like the original Abu Bakr, Baghdadi is also reputed to come from the Prophet’s Quraysh clan. That, and his youth – born in 1971 – may have been factors in his selection as leader.

All accounts of his early life agree that he was a quiet, scholarly and devout student of Islam, taking a doctorate at the Islamic University of Baghdad. Some even say he was shy, and a bit of a loner, living for 10 years in a room beside a small Sunni mosque in western Baghdad.

The word “charismatic” has never been attached to him.

Who is the leader of IS?

As a youth, Baghdadi had a passion for Koranic recitation and was meticulous in his observance of religious law. His family nicknamed him The Believer because he would chastise his relatives for failing to live up to his stringent standards.

Who is Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi?

What has happened to Baghdadi?

But by the time of the US-led invasion in 2003, he appears to have become involved with a militant Sunni group, heading its Sharia (Islamic law) committee. American troops detained him, and he was reportedly held in the detention centre at Camp Bucca in the south for most of 2004.

Camp Bucca (named after a fireman who died in the 9/11 attacks) housed up to 20,000 inmates and became a university from which many IS and other militant leaders graduated. It gave them an unrivalled opportunity to imbibe and spread radical ideologies and sabotage skills and develop important contacts and networks, all in complete safety, under the noses and protection of their enemies.

Baghdadi would also certainly have met in Camp Bucca many of the ex-Baathist military commanders with whom he was to form such a deadly partnership.

The low-profile, self-effacing Baghdadi rang no alarm bells with the Americans. They released him, having decided he was low-risk.

But he went on to work his way steadily up through the insurgent hierarchy, virtually unknown to the Iraqi public.

By the time Baghdadi took over in 2010, the curtains seemed to be coming down for the jihadists in the Iraqi field of “savagery”.

But another one miraculously opened up for them across the border in neighbouring Syria at just the right moment. In the spring of 2011, the outbreak of civil war there offered a promising new arena of struggle and expansion. The majority Sunnis were in revolt against the oppressive regime of Bashar al-Assad, dominated by his Alawite minority, an offshoot of Shia Islam.

Baghdadi sent his men in. By December 2011, deadly car bombs were exploding in Damascus which turned out to be the work of the then shadowy al-Nusra Front. It announced itself as an al-Qaeda affiliate the following month. It was headed by a Syrian jihadist, Abu Mohammed al-Jawlani. He had been sent by Baghdadi, but had his own ideas.

Jostling with a huge array of competing rebel groups in Syria, al-Nusra won considerable support on the ground because of its fearless and effective fighting skills, and the flow of funds and foreign fighters that support from al-Qaeda stimulated. It was relatively moderate in its salafist approach, and cultivated local relationships.

Al-Nusra was slipping out of Baghdadi’s control, and he didn’t like it. In April 2013, he tried to rein it back, announcing that al-Nusra was under his command in a new Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (Syria or the Levant). Isis, or Isil, was born.

What’s in a name?

During the short and turbulent period over which it has imposed itself as a major news brand, so-called Islamic State has confused the world with a series of name changes reflecting its mutations and changing aspirations, leaving a situation where there is no universal agreement on how to refer to it.

But Jawlani rebelled, and renewed his oath of loyalty to al-Qaeda’s global leadership, now under Ayman al-Zawahiri following Bin Laden’s death in 2011. Zawahiri ordered Baghdadi to go back to being just the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) and leave al-Nusra as the al-Qaeda Syria franchise.

It was Baghdadi’s turn to ignore orders from head office.

Before 2013 was out, Isis and al-Nusra were at each other’s throats. Hundreds were killed in vicious internecine clashes which ended with Isis being driven out of most of north-west Syria by al-Nusra and allied Syrian rebel factions. But Isis took over Raqqa, a provincial capital in the north-east, and made it its capital. Many of the foreign jihadists who had joined al-Nusra also went over to Isis, seeing it as tougher and more radical. In early 2014, al-Qaeda formally disowned Isis.

Isis had shaken off the parental shackles. But it had lost a lot of ground, and was bottled up. One of its main slogans, Remaining and Expanding, risked becoming empty. So where next?

Fortune smiled once more. Back in Iraq, conditions had again become ripe for the jihadists. The Americans had gone, since the end of 2011. Sunni areas were again aflame and in revolt, enraged by the sectarian policies of the Shia Prime Minister, Nouri Maliki. Sunnis felt marginalised, oppressed and angry.

When Isis decided to move, it was pushing at an open door. In fact, it had never really left Iraq, just gone into the woodwork. As it swept through Sunni towns, cities and villages with bewildering speed in June 2014, sleeper cells of salafist jihadists and ex-Saddamist militants and other sympathisers broke cover and joined the takeover.

With the capture of Mosul, Isis morphed swiftly into a new mode of being, like a rocket jettisoning its carrier. No longer just a shadowy terrorist group, it was suddenly a jihadist army holding large stretches of territory, ruling millions of people, and not only threatening the Iraqi state, but challenging the entire world.

The change was signalled on 29 June by the proclamation of the “Islamic State”, replacing all previous incarnations, and the establishment of the “caliphate”. A few days later, the newly anointed Caliph Ibrahim, aka Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, made a surprise appearance in Mosul in the pulpit of the historic Grand Mosque of al-Nuri, heavily laden with anti-Crusader associations. He called on the world’s Muslims to rally behind him.

By declaring a caliphate and adopting the generic “Islamic State” title, the organisation was clearly setting its sights far beyond Syria and Iraq. It was going global.

Announcing a caliphate has huge significance and resonance within Islam. While it remains the ideal, Bin Laden and other al-Qaeda leaders had always shied away from it, for fear of failure. Now Baghdadi was trumping the parent organisation, setting IS up in direct competition with it for the leadership of global jihadism.

A caliphate (khilafa) is the rule or rein of a caliph (khalifa), a word which simply means a successor – primarily of the Prophet Muhammad. Under the first four caliphs who followed after he died in 632, the Islamic Caliphate burst out of Arabia and extended through modern-day Iran to the east, into Libya to the west, and to the Caucasus in the north.

The Umayyad caliphate which followed, based in Damascus, took over almost all of the lands that IS would like to control, including Spain. The Baghdad-based Abbasid caliphate took over in 750 and saw a flowering of science and culture, but found it hard to hold it all together, and Baghdad was sacked by the Mongols in 1258.

Emerging from that, the Ottoman Empire, based in Constantinople (Istanbul), stretched almost to Vienna at its peak, and was also a caliphate, though the distinction with empire was often blurred. The caliphate was finally abolished by Ataturk in 1924.

So when Baghdadi was declared Caliph of the Islamic State, it was an act of extraordinary ambition. He was claiming no less than the mantle of the Prophet, and of his followers who carried Islam into vast new realms of conquest and expansion.

For most Islamic scholars and authorities, not to mention Arab and Muslim leaders, such claims from the chief of one violent extremist faction had no legitimacy at all, and there was no great rush to embrace the new caliphate. But the millennial echoes it evoked did strike a chord with some Islamic romantics – and with some like-minded radical groups abroad.

Four months after the proclamation, a group of militants in Libya became the first to join up by pledging allegiance to Baghdadi, followed a month later by the Ansar Beit al-Maqdis jihadist faction in Egypt’s Sinai. IS’s tentacles spread deeper into Africa in March 2015 when Boko Haram in Nigeria took the oath of loyalty. Within a year, IS had branches or affiliates in 11 countries, though it held territory in only five, including Iraq and Syria.

It was in those two core countries that Baghdadi and his followers started implementing their state project on the ground, applying their own harsh vision of Islamic rule.

To the outside world, deprived of direct access to the areas controlled by IS, one of the most obvious and shocking aspects of this was their systematic destruction of ancient cultural and archaeological heritage sites and artefacts.

Interactive

Use the slider below to compare before and after images

September 2015

August 2015

Some of the region’s best-known and most-visited sites were devastated, including the magnificent temples of Bel and Baalshamin at Palmyra in Syria, and the Assyrian cities of Hatra and Nimrud in Iraq.

It wasn’t just famous archaeological sites that came under attack. Christian churches and ancient monasteries, Shia mosques and shrines, and anything depicting figures of any sort were destroyed, and embellishments removed even from Sunni mosques. Barely a month after taking over Mosul, IS demolition squads levelled the 13th Century shrine of the Imam Awn al-Din, which had survived the Mongol invasion.

All of this was absolutely in line with IS’s puritanical vision of Islam, under which any pictorial representation or shrine is revering something other than Allah, and any non-Muslim structures are monuments of idolatry. Even Saudi kings and princes to this day are buried without coffins in unmarked graves.

By posting videos of many of these acts which the rest of the world saw as criminal cultural vandalism, IS also undoubtedly intended to shock. In that sense, it was the cultural equivalent of beheading aid workers.

And there was a more practical and profitable side to the onslaught on cultural heritage. In highly organised manner, IS’s Treasury Department issued printed permits to loot archaeological sites, and took a percentage of the proceeds.

That was just the tip of the iceberg of a complex structure of governance and control put in place as IS gradually settled into its conquests, penetrating into every aspect of people’s lives in exactly the same way as Saddam Hussein’s intelligence apparatus had done.

Captured documents published by Der Spiegel in 2015 give some idea of the role of ex-Baathist regime men in setting up and running IS in a highly structured and organised way, with much emphasis on intelligence and security.

Residents of Sunni strongholds like Mosul and Falluja in Iraq, and Raqqa in Syria, found that IS operatives already knew almost everything about everybody when they moved in and took over in 2014.

At checkpoints, ID cards were checked against databases on laptops, obtained from government ration or employee registers. Former members of the security forces had to go to specific mosques to “repent”, hand over their weapons and receive a discharge paper.

“At first, all they did was change the preachers in the mosques to people with their own views,” said a Mosul resident who fled a year later.

“But then they began to crack down. Women who had been able to go bare-headed now had to cover up, first with the headscarf and then with the full face-veil. Men have to grow beards and wear short-legged trousers. Cigarettes, hubble-bubble, music and cafes were banned, then satellite TV and mobile phones. Morals police [hisba] vehicles would cruise round, looking for offenders.”

A Falluja resident recounted the story of a taxi-driver who had picked up a middle-aged woman not wearing a headscarf. They were stopped at an IS checkpoint, the woman given a veil and allowed to go, while the driver was sent to an Islamic court, and sentenced to two months’ detention and to memorise a portion of the Koran. If you fail to memorise, the sentence is repeated.

“They have courts with judges, officials, records and files, and there are fixed penalties for each crime, it’s not random,” said the Falluja resident, speaking when IS still controlled the city. “Adulterers are stoned to death. Thieves have their hands cut off. Gays are executed by being thrown off high buildings. Informers are shot dead, Shia militia prisoners are beheaded.”

Severed heads on park fences: A diary of life under IS

An activist based in Raqqa from a group called Al-Sharqiya 24 has been keeping a diary of what life is like under Islamic State group rule.

Life under ‘Islamic State’: Diaries

IS departments carried the organisation’s grip into every corner of life, including finance, agriculture, education, transport, health, welfare and utilities.

School curricula were overhauled in line with IS precepts, with history rewritten, all images being removed from schoolbooks and English taken off the menu.

“One thing you can say is this,” said the Mosul resident after IS took over. “There is absolutely no corruption, no wasta [knowing the right people and pulling strings]. They are totally convinced they are on the right track.”

One story tells a lot about IS and its ways.

As Iraqi security forces were pressing forward in areas around Ramadi in early 2016, civilians were fleeing the battle – and IS fighters, losing the day, were trying to sneak out too.

Two women, running from the combat zone, approached a police checkpoint.

As they were being waved through to safety, one of the women suddenly turned to the police, pointed at the other, and said : “This is not a woman. He’s an IS emir [commander].”

The police investigated, and it was true. The other woman was a man, who had shaved, and put on makeup and women’s clothes. He turned out to be top of the list of wanted local IS commanders.

“When IS arrived, he killed my husband, who was a policeman, raped me, and then took me as his wife,” the woman told the police.

“I put up with him all this time, waiting to avenge my husband and my honour,” she said. “I tricked him into shaving and putting on makeup, then denounced him to the police.”

How does IS treat women?

“Nour” is a woman from Raqqa, the so-called Islamic State’s (IS) former capital inside Syria. She managed to escape the city and became a refugee in Europe, where she met up with the BBC.

This story is based on her experiences and those of her two sisters, who were still inside the city when it was held by IS.

Taking on the world

Having taken over vast swathes of territory in Iraq with their lightning offensive in June 2014, the militants might have been expected to calm down and consolidate their gains.

But, like a shark that has to keep moving or else it will die, IS barely paused before initiating a new spiral of provocation and reprisals that was predictably to draw it into active conflict with almost all the major world powers.

Already, the June offensive had threatened the approaches to Baghdad, prompting the Americans to start bringing in hundreds of military advisers and trainers to see how to help the struggling Iraqi army.

Just two months later, the attack on Kurdish areas in the north triggered US air strikes in defence of the Kurdistan capital, Irbil, and then to help stave off the threat of genocide to the Yazidis. Fourteen other nations were to join the air campaign.

Ten days later, IS beheaded James Foley and the others followed, in line with the doctrine of exemplary brutality as punishment, deterrent and provocation. The most shocking was to come some months later, with the burning alive of the downed Jordanian pilot Moaz al-Kasasbeh. Shock intended.

The US-led bombing campaign was extended to Syria in September 2014 after IS besieged the Kurdish-held town of Kobane on the Turkish border. Coalition air strikes turned the tide there. IS lost hundreds of fighters killed at Kobane and elsewhere. More revenge was called for. IS turned abroad.

In the three years following the declaration of the “caliphate” in 2014, at least 150 attacks in 29 countries across the globe were either carried out or inspired by IS, with well over 2,000 victims killed.

The attacks carried the same message of punishment, deterrence and provocation as the hostage beheadings, while also demonstrating IS’s global reach.

At the same time, they carried through the militants’ doctrine of distracting the enemy by setting fires in different locations and making him squander resources on security. For IS, “the enemy” is everybody who does not embrace it. The world is divided into Dawlat al-Islam, the State of Islam, and Dawlat al-Kufr, the State of Unbelief.

The most consequential of these atrocities were the downing of a Russian airliner over Sinai on 31 October 2015 and the Paris attacks on 13 November, provoking both Russia and France to intensify air strikes on IS targets in Syria.

The lone-wolf massacre at a gay club in Orlando, Florida, on 12 June 2016, while apparently inspired rather than organised by IS, would undoubtedly further stiffen the US’s already steely resolve to finish the organisation.

Had IS gone mad? It seemed determined to take on the whole world. It was goading and confronting the Americans, the Russians, and a long list of others. By its own count, it had a mere 40,000 fighters at its command (other estimates went as low as half that).

Could it really challenge the global powers and hope to survive? Or would President Barack Obama and his successor Donald Trump be able to fulfil Mr Obama’s pledge to “degrade and ultimately destroy” the organisation?

Final showdown

If there seemed to be something apocalyptic about IS’s “bring it on” defiance, that’s because there was.

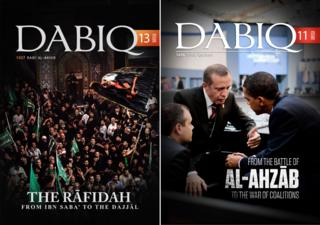

When the organisation first brought out its online magazine – a major showcase and recruitment tool – just a month after the “caliphate” was declared, it was not by chance that it was named Dabiq.

A small town north of Aleppo in Syria, Dabiq is mentioned in a hadith (a reported saying of the Prophet Muhammad) in connection with Armageddon. In IS mythology, it is the scene where a cataclysmic showdown will take place between the Muslims and the infidels, leading to the end of days. Each issue of Dabiq begins with a quote from Abu Musab Zarqawi: “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify – by Allah’s permission – until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.”

The prospect of taking part in that final glorious climax, achieving martyrdom on the path of Allah and an assured place in paradise, is one of the thoughts inspiring those heeding the IS call to jihad.

That could help explain why the organisation seemed to enjoy an endless supply of recruits willing to blow themselves to pieces in suicide attacks, which it calls “martyrdom-seeking operations” (suicide is forbidden in Islam). Hundreds have died in this way, and they happen virtually daily.

It’s been one of the elements that made IS a formidable fighting force hard to destroy even in strictly military terms.

The Baathist legacy at the core of IS

IS is in many respects a project of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s outlawed Baath party, but now with a different ideology. Former agents or officers of Saddam Hussein’s regime dominate its leadership… They represent a battle-hardened and state-educated core that would likely endure (as they have done through US occupation and a decade of war) even if the organisation’s middle and lower cadres are decimated.

What made IS so formidable?

The head of security and intelligence for the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq, Masrour Barzani, tells the story of a frustrated would-be suicide bomber who screamed at his captors: “I was just 10 minutes away from being united with the Prophet Muhammad!”

“They think they’re winners regardless of whether they kill you or they get killed,” says Barzani. “If they kill you, they win a battle. If they get killed, they go to heaven. With people like this, it’s very difficult to deter them from coming at you. So really the only way to defeat them is to eliminate them.”

Probably for the first time in military history since the Japanese kamikaze squadrons of World War Two, suicide bombers are used by IS not only for occasional terrorist spectaculars, but as a standard and common battlefield tactic.

Virtually all IS attacks begin with one or several suicide bombers driving explosives-rigged cars or trucks at the target, softening it up for combat squads to go in. So much so that the “martyrdom-seekers” have been called the organisation’s “air force”, since they serve a similar purpose.

Formidable though that is, IS as a fighting force is much more than a bunch of wild-eyed fanatics eager to blow themselves up. For that, they have Saddam Hussein to thank.

“The core of IS are former Saddam-era army and intelligence officers, particularly from the Republican Guard,” said an international intelligence official. “They are very good at moving their people around, resupply and so on, they’re actually much more effective and efficient than the Iraqi army are. That’s the hand of former military staff officers who know their business.”

“They are very professional,” adds Masrour Barzani. “They use artillery, armoured vehicles, heavy machinery etc, and they are using it very well. They have officers who know conventional war and how to plan, how to attack, how to defend. They really are operating on the level of a very organised conventional force. Otherwise they’d be no more than a terrorist organisation.”

The partnership with the ex-Baathists, going back to Zarqawi’s early days in Iraq, was clearly a vital component in IS success.

But that did not mean its fighters were invincible on the battlefield, even in the early days of stunningly rapid expansion. The Kurds in north-east Syria were fighting IS off with no outside help for a year before anybody noticed. And even now, IS makes what would conventionally be seen as costly mistakes.

In December 2015, for example, they lost several hundred fighters in one abortive attack east of Mosul alone, and probably 2,500 altogether that month alone. Pentagon officials said coalition air strikes killed some 50,000 IS militants in Iraq and Syria between August 2014 and the end of 2016.

But IS initially seemed to have little difficulty making up the numbers. With a population of perhaps 10 million acquiescent Sunnis to draw on, in Iraq and Syria, most recruiting was done locally. Clearly, had it remained in place, there would soon have been a new generation of young militants drawn from local sources.

“I didn’t join out of conviction,” says Bakr Madloul, a 24-year-old bachelor who was arrested in December at his home in a Sunni quarter in southern Baghdad and accused of taking part in deadly IS car bomb attacks on mainly Shia areas, which he admits.

Bakr says he was working as a construction foreman in Kurdistan when IS took over Mosul. He was detained for questioning by Kurdish security, and met a militant in jail who persuaded him to go to Mosul, where he joined up with IS and manned a checkpoint until it was hit by a Coalition air strike.

He was then sent back to his Baghdad suburb to help organise car bombings. The explosives-packed vehicles were sent from outside Baghdad, and his job was to place them where he was told by his controller, usually in crowded streets or markets.

“Only one of the five car bombs I handled was driven by a suicide bomber,” he says. “I spoke to him. He was 22 years old, an Iraqi. He believed he would go to paradise when he died. It’s the easiest and quickest way to Heaven. They strongly believe this. They would blow themselves up to get to Heaven. There were older ones in their 30s and 40s.”

“I asked my controllers more than once, ‘Is it OK to kill women and children?’ They would answer, ‘They’re all the same.’ But to me, killing women and children, I didn’t feel at all comfortable about that. But once you’re in, you’re stuck. If you try to leave, they call you a murtadd, an apostate, and they’ll kill you or your family.”

Bakr knows he will almost certainly hang. Since we spoke, he has in fact been given two death sentences. I asked him if he would do the same things over if he had his life again. He laughed.

“Absolutely not. I would get out of Iraq, away from IS, away from the security forces. I took this path without realising the consequences. There is no way back. I see that now.”

But up in Kurdistan, another IS prisoner, Muhannad Ibrahim, has no such regrets.

A 32-year-old from a village near Mosul with a wife and three children, he was a construction worker for a Turkish company when IS took over the city. Two of his older brothers had died fighting the Americans there in 2004 and 2006. He joined IS without hesitation and was commanding a small detachment when he was captured in a battle with the Kurds.

“We were being oppressed by the Shia, they were always insulting and bothering us,” he says. “But that’s not the main motivation, religious conviction is more important. All my family is religious, praise be to Allah. I came to IS through my faith and religious principles.”

“If I had my time over again, I would take the same path, the same choices. Because I am convinced by this thing, I have to go to the end. Either I am killed, or Allah will decree some other fate for me.”

Rising to the challenge

Just as the 9/11 Twin Towers atrocity in 2001 had left the US and its allies with no alternative but to strike back with extreme force, the challenge mounted by IS through its numerous provocative outrages in the region and around the world could not be ignored – nor was it meant to be.

But rooting out the militants from Iraq and Syria was always going to be much more complex than the campaign unleashed more than a decade earlier against al-Qaeda and its Taliban hosts in Afghanistan.

There was never any real question of a wholesale Coalition invasion of either country. Air strikes were one thing, but putting in vast numbers of troops on the ground would be something else.

Syria was embroiled in a bewilderingly complicated civil war. Iraq was also in turmoil. US forces had only pulled out three years earlier. There was no appetite for a repeat of an invasion which was almost universally seen as a disastrous blunder with lasting consequences.

But uprooting the militants could not be done by air power alone. Reliable, motivated partner forces on the ground would be needed. In both countries, they were in short supply.

In Syria, the US and its allies were already engaged with some of the motley array of Syrian rebel groups. But they never amounted to the kind of focused, cohesive forces that the Coalition was looking for – they were fragmented, fractious, increasingly Islamist in tone, and largely bent on overthrowing the Assad regime rather than turning on IS.

In Iraq, the regular armed forces were in disarray after collapsing like a house of cards in the face of the onslaught on Mosul by a few hundred IS militants. Much work would have to be done to weld them into a motivated and competent fighting force.

In both countries it was to the Kurds in the north that the Americans and their Coalition partners first turned as their most hopeful immediate allies.

The Kurdish Peshmerga forces in northern Iraq had a long relationship with the Western Coalition powers. In 2003, US special forces fought alongside them to clear Islamist militants from mountain positions near the Iranian border just before the invasion against Saddam Hussein, in which they were partners.

Humiliated by the loss of vast areas of territory to the lightning IS assault in early August 2014, the Peshmerga needed no encouragement to hit back. Less than two weeks later, with Coalition air support, they recaptured the strategic Mosul dam.

In the months that followed, they slowly clawed back much of the ground they had lost, including Sinjar in November 2015, in operations closely co-ordinated with Coalition air strikes.

But in the rest of Iraq, the picture was much messier. Iraqi government forces were able to halt the IS thrust southwards towards the capital, Baghdad, but made little early progress pushing back into the mainly Sunni areas where the militants had dug in.

It was Iranian-backed Shia militias, whose emergence was consolidated under the IS threat, that made the running in the initial phases of the campaign to oust the militants, driving them out of areas north-east of Baghdad near the Iranian border and pursuing them westwards until the eventual recapture of Saddam Hussein’s hometown Tikrit in the Tigris river valley in March 2015.

“If it weren’t for Iran, the democratic experiment in Iraq would have fallen,” said Hadi al-Ameri, leader of the Iranian-backed Badr Organisation, one of the biggest Shia fighting groups, known as the Hashd al-Shaabi or Popular Mobilisation (PM), that rose in defence of Baghdad and the south.

“Obama was sleeping, and he didn’t wake up until IS was at the gates of Irbil. When they were at the gates of Baghdad, he did nothing. Were it not for Iran’s support, IS would have taken over the whole Gulf, not just Iraq.”

But in the Sunni heartlands of Anbar province to the west of Baghdad the Iraqi state forces were struggling.

In May 2015, IS militants captured the provincial capital, Ramadi. At the same time, they spread their grip in Syria, taking the iconic city of Palmyra (Tadmur) in the desert east of Homs. It was a clear signal that while the organisation may have been dealt some setbacks it was still at the height of its powers and capable of exploiting any weaknesses it found.

But the Americans were quietly busy preparing for the real war on IS. They had poured billions into rebuilding the Iraqi army after 2003, only to see much of it go to pieces under pressure because so much was wrong with its foundations.

Now, putting in several thousand advisers, they focused on training and equipping the key Iraqi special forces – the Counter-Terrorism Service (CTS), otherwise known as the Golden Division – that was to play a crucial role spearheading the drive against the militants.

The systematic lashback began with Anbar province and the eventual recapture of Ramadi at the end of 2015 and early 2016, a grinding and costly operation with close Coalition air support. There was huge destruction and the displacement of most of the city’s largely Sunni population. There were also tensions over the deployment of Iranian-backed, mainly Shia militias in core Sunni areas, though they were largely kept out of the city itself.

The recapture of Ramadi tightened the noose around the even more iconic centre of Sunni sentiment at nearby Falluja, where militants had fought two major battles with the Americans in 2004. Government and PM forces began closing in around the city in early 2016, soon after taking Ramadi.

By now, after a lot of testing and assessing, the Americans and their allies, working closely with local forces, were clearly embarked on a comprehensive strategy to “degrade and ultimately destroy” IS wherever it could be found.

The broad lines were spelled out in February 2016 by Lt Gen Sean McFarland, then the commanding general of the Coalition’s Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve.

“The campaign has three objectives: to destroy the ISIL parent tumour in Iraq and Syria by collapsing its power centres in Mosul and Raqqa; two, to combat the emerging metastases of the ISIL tumour worldwide; and three, to protect our nations from attack.”

Next step on the road to Mosul, the battle for Falluja was joined in late May 2016 and took just over a month of assaults, bombardments and air strikes to complete, with civilians again paying a heavy price. IS fighters deployed their full range of battle tactics, with snipers, booby-traps and suicide bombers making advance difficult and dangerous for the attacking forces.

Despite the attrition suffered by the Iraqi forces, especially the elite CTS forces, it was not long before eyes turned to the big prize – Mosul. With President Obama due to bow out early in the new year, the Americans were getting impatient.

In peacetime roughly 10 times the size of either Falluja or indeed the IS “capital” Raqqa, Mosul was never going to be an easy nut to crack. It had fallen to the militants in a matter of hours in 2014. By the time the government and Coalition campaign to dislodge them was finally launched in mid-October 2016, IS had had nearly two-and-a-half years to dig in and prepare its defences.

Inside IS’s ruined ‘capital’

There is a moment in the journey into Raqqa when you leave the real world behind. After the bombed-out Samra bridge, any signs of normal life vanish.

Turn right at the shop that once sold gravestones – its owner is long gone – and you are inside the city.

Ahead lies nothing but destruction and grey dust and rubble.

This is a place drained of colour, of life, and of people. In six days inside Raqqa, I didn’t see a single civilian.

The city fit for no-one

Marshalled against a band of militants variously estimated at between 2,000 and 12,000 with a hard core probably closer to 4,000 or 5,000, was a vast assembly of government and auxiliary forces, estimated at around 100,000, counting regular army and federal police units, Kurdish Peshmerga forces, and the Popular Mobilisation, including some Sunni and minority volunteers as well as Shia militias.

It was an epic battle that was to last nine months. Government forces slowly battered their way in around the city through dozens of outlying villages and finally into Mosul’s eastern half, which was declared “liberated” towards the end of January 2017. Then it was on to the western side of the river and the old city, with its dense warren of narrow streets.

The area around the ancient Great Mosque of al-Nuri, where Abu Bakr al-Baghdad had made his only public appearance as the newly-anointed “caliph”, was the last to fall. The mosque was blown up, almost exactly three years after the declaration of the IS “caliphate”. The evidence was that IS itself had destroyed it, rather than let it fall into “infidel” hands. The Iraqi Prime Minister, Haider al-Abadi, saw this as “official recognition of defeat” by the militants. It signalled, he said, “the collapse of the IS caliphate and a grand military victory”.

It was indeed a monumental achievement, a massive body-blow to the IS state project. The city had been, as a senior Western official in northern Iraq put it, “the beating heart of IS”, in real terms much more important than Raqqa in Syria.

But it came at huge cost. The years of preparation and months of battering that it took to dislodge a few thousand militants stood in stark contrast to the ease with which they had rolled into the city virtually unopposed in June 2014. Some estimates put the number of civilians killed at more than 40,000. At least 1,200 Iraqi security personnel also died in battle. The damage was estimated at $50bn. Hundreds thousands of mainly Sunni inhabitants were displaced, and there were widespread allegations of abuses.

The weeks that followed saw a further rapid erosion of the group’s territorial position in Iraq. By the end of August 2017, it had been driven out of Tal Afar, an important town controlling the main road from Mosul towards Syria. A month later, another long-standing IS pocket in and around the mainly Sunni town of Hawija, west of Kirkuk, was also largely overrun by government and auxiliary forces.

In Iraq, that left IS in control only of the area in and around the town of al-Qaim, on the River Euphrates by the Syrian border in the far west of Anbar province.

Its presence in the country had been very radically degraded. But the organisation was still far from destroyed.

Across in Syria, the overall picture by the autumn of 2017 was roughly the same, despite the country’s very different, extremely complex and fast-moving situation.

In 2014 and 2015, IS had substantial holdings in Syria – it looked as though someone had spilled a bottle of black ink on its map. They controlled virtually the whole of Syria’s stretch of the Euphrates, from Albu Kamal on the Iraqi border, up through Deir al-Zour and Raqqa, the Tabqa dam, and on to Jarablus on the border with Turkey, one of several crossings that were lifelines for the militants. They held towns and villages to the east and north of Aleppo (including the near-mythical Dabiq) and other pockets further south, including Palmyra and nearby oilfields.

But this heyday did not last. In Syria, IS found itself facing, not one motley coalition of enemies as in Iraq, but three.

The Americans, despairing of Syrian rebel groups whose interests lay elsewhere, adopted the experienced Syrian Kurdish fighters of the YPG, the Popular Protection Units, as their main on-the-ground partners. They added on as many Arab and minority fighters as they could find to produce the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), their favoured vehicle against IS in Syria.

This did not go down at all well with the US’s Nato ally Turkey, which sees the YPG and their parent political body, the Democratic Unity Party (PYD), as terrorists because of their affiliation to Turkey’s own Kurdish rebels, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Often seeming to be working at cross-purposes to the Americans, Ankara set up its own coalition from among the Syrian opposition groups it had been backing and facilitating for years.

IS also received attention from a third coalition, grouping Syrian government forces, Iran and Russia. The Russians carried out air strikes against IS positions partly with the same kind of motivation as the Western Coalition – revenge for the downing by IS of the Russian airliner over Sinai in October 2015 – but their real strategic interest was different.

The Russians and Iranians were bent on securing their investment in the Assad regime, helping it restore its authority in the country, and pre-empting any move by the Americans and their allies to block a link-up between eastern Syria and western Iraq that would give Tehran a direct land connection from Iran all the way to Lebanon.

That thought may have been somewhere in Washington’s head, but its primary concern was hitting and destroying IS.

Turkey for its part had a different overriding preoccupation: to prevent the Syrian Kurds from expanding and joining up the areas they controlled along the southern side of the Turkey-Syria border.

Despite these conflicting motivations, for IS the result was the same – pressure on many fronts. The US-backed SDF made the most headway, systematically whittling away IS assets step-by-step, but Turkey and Syrian government forces were also on the march.

As early as September 2014, US air strikes had helped prevent IS taking over the Kurdish-held town of Kobane on the border with Turkey. After that, the SDF were pushing forward. By October 2016, IS had lost all access to the Turkish border, a huge logistical setback – virtually all foreign jihadists bound for both Syria and Iraq had come that way, apart from other advantages.

The Turkish-backed Syrian rebels also played their part, taking over IS-held areas north and east of Aleppo – including Dabiq, which fell in a mundane enough manner with none of the apocalyptic “burning of the Crusader armies” heralded in IS mythology.

Gradually the militants’ tide receded further and further down the Euphrates valley, with the SDF, backed by perhaps 2,000 US special forces with artillery and air power, doing most of the pushing. By November 2016, the SDF were in a position to launch a campaign to isolate and eventually attack the IS “capital”, Raqqa. The assault on the city itself began in early June 2017.

By then, much of the population and many IS fighters had already fled, with most of the militants heading further downstream to the final major city largely under their control – another provincial capital, Deir al-Zour.

But before the recapture of Raqqa had been completed, Russian- and Iranian-backed Syrian government forces were already thrusting towards Deir al-Zour, where a military base and airport had held out against the IS militants for almost three years. To get there, the government forces had recaptured Palmyra (for the second time) in March and pushed eastwards along the road to take Sukhna in August before reaching Deir al-Zour itself in September.

US-backed SDF forces had already bypassed the yet-to-fall Raqqa and moved into oil-rich areas to the east of Deir al-Zour, laying claim to oil and gasfields that would greatly bolster the Kurds’ ambitions to run their own area in the north of the country – or at least strengthen their hand in eventual negotiations with Damascus.

So as 2017 moved into its final months, IS territorial control in Syria seemed to be as doomed as it was in Iraq – bottled up in a small patch straddling the border around al-Qaim in western Iraq and Albu Kamal in Syria. Rooting the militants out from there would not necessarily be a simple task in a fiercely tribal area prone to defying governments.

But to all intents and purposes, the IS dream of administering and expanding a thriving Islamic state in the two countries as the core of a growing global caliphate had crashed in flames.

So had IS been virtually destroyed as well as severely degraded? Was it time to celebrate its demise?

It had certainly been dealt crippling blows in terms of functioning as a territorial state. That project lay in ruins. The administrative structures it had set up had been swept away. Major sources of finance had been cut off – from the oilfields it had controlled, taxes imposed on the millions of Iraqis and Syrians it had ruled, and cash coming in across the border with Turkey. It could no longer attract thousands of foreign jihadists or recruit locals to replace the 60,000 IS fighters the Americans believe have died since the heady days of June 2014.

With virtually all of their urban holdings lost, the militants were shrinking back into the shadows and deserts. Many of their leaders had also been killed, although Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi himself apparently eluded the hunt, issuing a defiant audio statement in September 2017. Among the known dead were Mohammed Emwazi, “Jihadi John”, killed by a drone strike in Syria in late 2015.

But all of this had been long foreseen by the leadership. In May 2016, the man regarded as the organisation’s real Number Two, spokesman and head of external operations Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, made a lengthy statement already foreshadowing the next phase of IS existence.

“You will never be victorious. You will be defeated,” he told the Americans. “Do you think that victory comes by killing one leader or another? That would be a fake victory!”

“Or do you consider defeat to be the loss of a city or the loss of territory? Were we defeated when we lost the cities in Iraq [in 2007-8] and were in the desert without any city or land? And would we be defeated, and you victorious, if you were to take Mosul or Sirte or Raqqa, or even all the cities, and we were to return to our previous situation? Absolutely not! True defeat is the loss of will and desire to fight.“

Adnani, who as spokesman had announced the birth of “Islamic State” and the caliphate in June 2014, may not have lost the will and desire to fight. But he did lose his life. He was killed by an American air strike near Aleppo in August 2016.

He was right to suggest that the targeted killing of militant leaders has in general had little discernible impact on the course of movements, psychologically important though it may be.

But the Iraqi expert on radical movements, Hisham al-Hashemi, believes the case of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi might be different. The Americans are unlikely to rest until they have killed Baghdadi, not least because of their belief that he personally repeatedly raped an American NGO worker, Kayla Mueller, and then had her killed in early 2015.

“IS’s future depends on Baghdadi,” Hashemi said, speaking at a time when IS still controlled huge swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria.

“If he is killed, it will split up. One part would stay on his track and announce a new caliphate. Another would split off and return to al-Qaeda. Others would turn into gangs following whoever is strongest.”

“The source of his strength is that he brought about an ideological transformation, blending jihadist ideas with Baathist intelligence security methods, enabling him to create this quasi-state organisation.”

Baghdadi’s death might not have such an impact in the new situation. But his special talents could come into their own again should conditions in either or both of those countries, or elsewhere, once again favour a comeback by the militants.

That is not so fanciful, even amid the smoking wreckage of the IS above-ground infrastructure.

In Iraq, the burning Sunni grievances against the Shia-dominated Baghdad government that allowed IS to make its astonishing advances in 2014 have not been seriously addressed. American officials are already referring to the danger of an “AQI-2” emerging – a second al-Qaeda in Iraq. It has happened before.

The wholesale destruction of Sunni towns and cities in the drive against IS and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Sunnis may even have aggravated those grievances, providing fertile ground for militants to infiltrate back.

There is an optimistic argument that the united cross-sectarian effort that it took to drive the militants out may have sown the seeds of a new Iraqi nationalism. But the fact remains that the Sunni community has been crushed, and the Shia majority dominates both politically and through the proliferation of its powerful militias. Political leaderships in Baghdad have signally failed to promote any serious national reconciliation since 2003.

“IS was essentially an Iraqi creation,” said a senior Western intelligence official, speaking shortly before the militants were ousted from Mosul.

“The tragic reality is that at the moment, it is the main Sunni political entity in Iraq. From the West, it’s looked at as a kind of crazed cult. Here in Iraq it represents an important constituency. It represents a massive dissatisfaction, the alienation of a whole sector of the population.”

Putting IS on trial

A young man wearing a shabby, brown prisoner’s outfit stands before three black-robed judges in a tiny, provincial courtroom, shaking nervously.

After sipping some water, he confirms his name: Abdullah Hussein. He is accused of fighting for so-called Islamic State (IS).

“The decision of the court has been taken according to articles 2 and 3 of the 2005 Counterterrorism Law,” states the judge. “Death by hanging.”

And then Hussein – who, like many suspects here, was picked up on the Mosul frontline – breaks down crying.

Inside the Iraqi courts sentencing IS suspects to death

Much work remains to be done if that sobering assessment is to be reversed. And Baghdad meanwhile faces multiple challenges that might help tip it back into the state of chaos in which the militants could thrive.

The state’s coffers are empty at a time when the reconstruction bill is estimated conservatively at $100bn. Corruption is endemic. Apart from the Sunni issue, Baghdad politics is in turmoil, with deep rivalries between Shia factions with greater or lesser attachment to Iran. And the threat of secession by the Kurds in the north, after the September 2017 independence referendum, could bring further instability.

The very least that could be expected post-Mosul was an indefinite period of low-level insurgency, with bomb blasts and suicide attacks in different parts of the country, especially aimed, as before, at mainly Shia areas. It was already happening. The US military’s Combating Terrorism Center reported that by mid-2017 there was already an average of 130 insurgent attacks taking place monthly in the “liberated” eastern half of Mosul.

And it was already happening next door in Syria too, with IS carrying out random deadly explosions in Damascus and elsewhere despite its stark loss of territory. Although it was obvious by late 2017 that the Assad government with its Russian and Iranian backers were prevailing, the final pattern of control and governance country-wide remained uncertain.

There were many ways in which further turmoil could ensue, not least the fact that, with US support, Kurdish forces had spread well beyond their own demographic comfort zone, causing huge resentment among some Sunni elements. As in Iraq, many Syrian Sunnis were bound to feel aggrieved by everything that had happened since the civil war broke out in 2011.

And where there were grievances, IS or its successors would surely be there to build on them.

Capitalising on chaos

IS had in any case been busy spreading its bets and developing other territorial possibilities beyond the “parent tumour” of Iraq and Syria.

Libya initially proved the most promising. It had just the kind of failed-state anarchy, the state of “savagery”, that left room for the jihadists to move in, forging alliances with local militants and disgruntled supporters of the overthrown regime of Muammar Gaddafi, just as they had done in Iraq.

IS signalled its arrival there in typical style, issuing a polished video in February 2015 showing a group of 21 bewildered Egyptian Christian workers in orange jumpsuits being beheaded on a Libyan beach, their blood mingling with the waters of the Mediterranean as a warning to the “Crusader” European countries on the other side of the sea that radical Islam was on the way.

The man who voiced that warning was believed to be the IS leader in Libya, an Iraqi called Wissam al-Zubaydi, also known as Abu Nabil. By coincidence, Zubaydi was killed in a US air strike on the same day IS struck in Paris, 13 November 2015.

The militants took over a big stretch of the coast and the central city of Sirte, which was to Muammar Gaddafi what Tikrit was to Saddam Hussein. Another American air strike in February killed (among nearly 50 other people) Noureddine Chouchane, reputedly an IS figure responsible for the deadly attacks on Western tourists in his native Tunisia.

But the IS presence in Libya soon came under pressure, with militias loyal to the Government of National Accord, which been born out of UN efforts, dislodging the militants from Sirte in the second half of 2016.

But they did not disappear. The Americans launched an air strike on IS elements south of Sirte in October 2017, their first such action in Libya since President Trump took over.

The militants were undoubtedly on the defensive in Libya. But it remained a deeply fragmented country, and its new government far from powerful or universally accepted. There would likely continue to be pockets of chaos there for the jihadists to exploit.

And there was no shortage of other possibilities being actively explored and developed – Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, the Philippines, Nigeria… wherever there were dysfunctional states and angry Muslims, there would be opportunities for IS, competing strongly with a diminished al-Qaeda as a dominant brand in the jihadist market.

Adding the extra risk for the West, that that competition could be another spur for spectacular terrorist attacks which they know are being actively plotted.

Long before IS lost almost all its territorial gains in Iraq and Syria, it was clear that the organisation, while trying its best to hold ground wherever it could, was trying to stay alive and assert itself (“Remaining and Expanding”) in other ways – renewed insurgency in the lost lands, constant propaganda and proselytising on the internet, and above all, a revitalised push to carry out acts of terror in the West, the more shocking the better.

As early as September 2014, just as IS was embarking on its provocative confrontation with the West, spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani urged the movement’s followers in graphic detail to kill the hated infidels.

“If you can kill a disbelieving American or European – especially the spiteful and filthy French – or an Australian, or a Canadian, or any other of the unbelievers waging war, including the citizens of the countries that entered a coalition against the Islamic State, then rely upon Allah, and kill him in any manner or way however it may be. Smash his head with a rock, slaughter him with a knife, run him over with your car, throw him down from a high place, choke him or poison him.”

In his statement in May 2016, al-Adnani signalled the organisation’s new stress on attacks inside Western countries in response to the drive against it in Iraq and Syria.

“Truly, the smallest act you do in their lands is more beloved to us than the biggest act done here; it is more effective for us and more harmful to them… Know that your targeting those who are called “civilians” is more beloved to us and more effective, as it is more harmful, painful, and a greater deterrent to them.”

Attacks in Europe and elsewhere intensified almost in direct proportion to IS’ loss of terrain in Iraq and Syria. Among the more notable were the truck assault in Nice, France, in July 2016 (at least 86 killed) and a similar attack in Berlin in December (12 killed), the Istanbul nightclub bombing in January 2017 (39 killed), and two vehicle and knife attacks in London in March and June 2017 (15 killed).

The attacks in London broke new ground for IS, and even more so the suicide bomb attack at the Manchester Arena in May 2017 in which more than 20 people died. A van attack in Barcelona in August in which 13 people were killed was also seen as an advance for the militants.

These kinds of attacks, often carried out by “lone wolves” and involving everyday implements that are impossible to control, were clearly a nightmare for security services.

Their job was made all the more challenging by studies showing that fewer than 20% of “successful” attacks in Europe and North America were carried out by jihadists who had gone to Syria or Iraq, and that most were perpetrated by citizens of the countries under attack.

While IS had managed to plant a small number of activists in the crowds of refugees and asylum seekers besieging the gates of Europe and the West, simply vetting them carefully would obviously not be enough.

Clearly, IS internet messaging was still powerful, resonating among the disaffected, the resentful, the alienated and disempowered.

The Americans, focusing largely on the military defeat of the militants, seemed taken aback by IS’s ability to keep up and even expand the challenge.

“When I consider how much damage we’ve inflicted and they’re still operational, they’re still capable of pulling off things like some of these attacks we’ve seen internationally, we have to conclude that we do not yet fully appreciate the scale or strength of this phenomenon,” said Lt Gen Michael Nagata, one of the top US Special Operations officers, quoted by the Combating Terrorism Center.

“We spend an inordinate amount of time and resources as the United States, but also as our partners, trying to not only defeat ISIS and their control of the physical caliphate, but their virtual space that they own,” added Thomas P Bossert, President Trump’s adviser on homeland security and counter-terrorism adviser.

“They’re proselytizing. It’s troubling.”

Clearly, tackling such a vague, ethereal and pervasive threat was a far cry from the clear-cut task of confronting IS fighters on the battlefield. The threat was not going to go away. Cyber-inspired lone wolf attacks could materialise at almost any time, any place. The price of relative safety would be eternal vigilance.

Battle for minds

The US and its allies were starting to come to grips with the cyber dimension of the challenge – and giving much less priority to the crucial problem of poor governance in the countries whose dysfunctionalities provided opportunities for the radicals to take root.

But there were other parts of IS’ complicated root system that were even harder to get at.

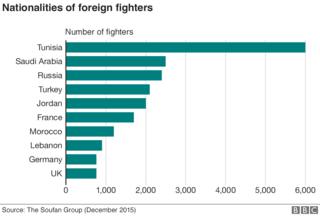

The New York-based security consultancy Soufan Group estimated that more than half of the 27,000 foreign jihadists making their way to Syria and Iraq in the first 18 months of the “Islamic State” were from the Middle East and North Africa.

Clearly, the “Caliphate” had appeal, despite – perhaps in some cases, because of – its graphically publicised brutality. While vowing to degrade and destroy the organisation, President Obama put his finger on the real challenge:

“Ideologies are not defeated with guns, they are defeated by better ideas, a more attractive and more compelling vision,” he said.

The complex art of IS propaganda