Home » Middle East »

How chemical weapons have helped Assad

After seven devastating years of civil war in Syria, which have left more than 350,000 people dead, President Bashar al-Assad appears close to victory against the forces trying to overthrow him.

So how has Mr Assad got so close to winning this bloody, brutal war?

A joint investigation by BBC Panorama and BBC Arabic shows for the first time the extent to which chemical weapons have been crucial to his war-winning strategy.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this map

Source: BBC Panorama and BBC Arabic research. Map built with Carto.

1. The use of chemical weapons has been widespread

The BBC has determined there is enough evidence to be confident that at least 106 chemical attacks have taken place in Syria since September 2013, when the president signed the international Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) and agreed to destroy the country’s chemical weapons stockpile.

Syria ratified the CWC a month after a chemical weapons attack on several suburbs of the capital, Damascus, that involved the nerve agent Sarin and left hundreds of people dead. The horrific pictures of victims convulsing in agony shocked the world. Western powers said the attack could only have been carried out by the government, but Mr Assad blamed the opposition.

The US threatened military action in retaliation but relented when Mr Assad’s key ally, Russia, persuaded him to agree to the elimination of Syria’s chemical arsenal. Despite the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and the United Nations destroying all 1,300 tonnes of chemicals that the Syrian government declared, chemical weapons attacks in the country have continued.

“Chemical attacks are terrifying,” said Abu Jaafar, who lived in an opposition-held part of the city of Aleppo until it fell to government forces in 2016. “A barrel bomb or a rocket kills people instantly without them feeling it… but the chemicals suffocate. It’s a slow death, like drowning someone, depriving them of oxygen. It’s horrifying.”

But Mr Assad has continued to deny his forces have ever used chemical weapons.

Karen Pierce, the United Kingdom’s permanent representative to the UN in New York, described the use of chemical weapons in Syria as “vile”.

“Not just because of the truly awful effects but also because they are a banned weapon, prohibited from use for nearly 100 years,” she said.

About the data

The BBC team considered 164 reports of chemical attacks from September 2013 onwards.

The reports were from a variety of sources considered broadly impartial and not involved in the fighting. They included international bodies, human rights groups, medical organisations and think tanks.

In line with investigations carried out by the UN and the OPCW, BBC researchers, with the help of several independent analysts, reviewed the open source data available for each of the reported attacks, including victim and witness testimonies, photographs and videos.

The BBC team had their methodology checked by specialist researchers and experts.

The BBC researchers discounted all incidents where there was only one source, or where they concluded there was not sufficient evidence. In all, they determined there was enough credible evidence to be confident a chemical weapon was used in 106 incidents.

The BBC team were not allowed access to film on the ground in Syria and could not visit the scenes of reported incidents, and therefore were not able to categorically verify the evidence.

However, they did weigh up the strength of the available evidence in each case, including the video footage and pictures from each incident, as well as the details of location and timing.

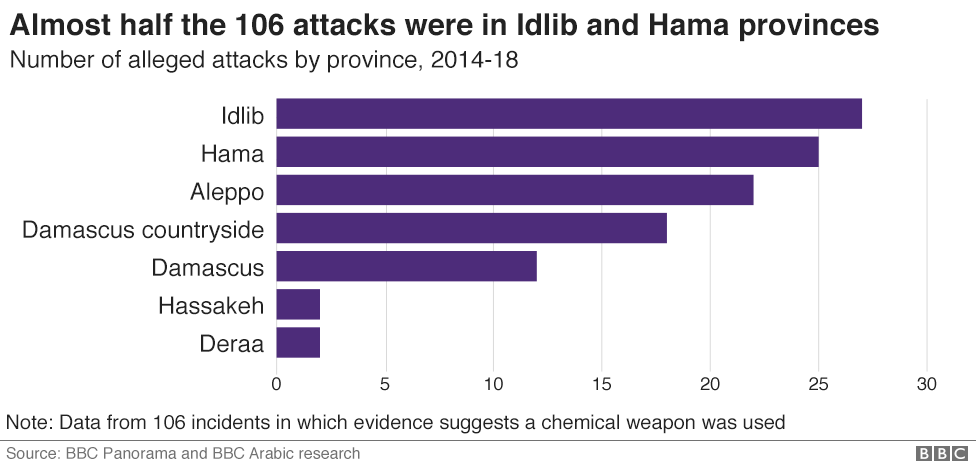

The highest number of reported attacks took place in the north-western province of Idlib. There were also many incidents in the neighbouring provinces of Hama and Aleppo, and in the Eastern Ghouta region near Damascus, according to the BBC’s data.

All of these areas have been opposition strongholds at various times during the war.

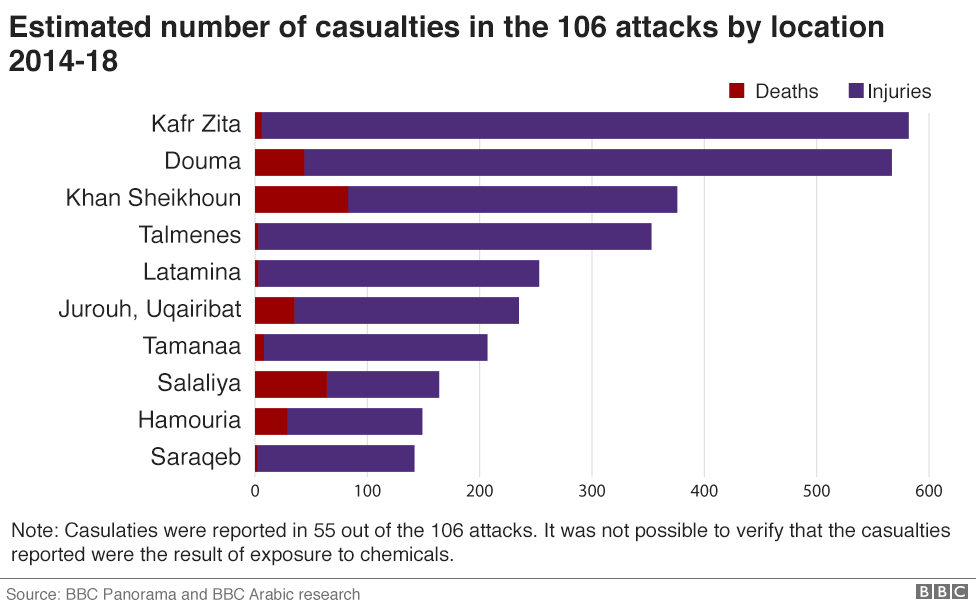

The locations where the most casualties were reported as a result of alleged chemical attacks were Kafr Zita, in Hama province, and Douma, in the Eastern Ghouta.

Both towns have seen battles between opposition fighters and government forces.

According to the reports, the deadliest single incident took place in the town of Khan Sheikhoun, in Idlib province, on 4 April 2017. Opposition health authorities say more than 80 people died that day.

Although chemical weapons are deadly, UN human rights experts have noted that most incidents in which civilians are killed and maimed have involved the unlawful use of conventional weapons, such as cluster munitions and explosive weapons in civilian populated areas.

2. The evidence points to the Syrian government in many cases

Inspectors from an OPCW-UN joint mission announced in June 2014 that they had completed the removal or destruction of all of Syria’s declared chemical weapons material, in line with the agreement brokered by the US and Russia after the 2013 Sarin attack.

“Everything that we knew to be there was either removed or destroyed,” said Mr Tangaere, one of the OPCW inspectors.

But, he explained, the inspectors only had the information they were given.

“All we could do was to verify what we’d been told was there,” he said. “The thing about the Chemical Weapons Convention is it’s all based on trust.”

The OPCW did, however, identify what it called “gaps, inconsistencies and discrepancies” in Syria’s declaration that a team from the watchdog is still trying to resolve.

In July 2018, the OPCW’s then-director general, Ahmet Üzümcü, told the UN Security Council that the team was “continuing its efforts to clarify all outstanding issues”.

Despite the June 2014 announcement that Syria’s declared chemical weapons material had been removed or destroyed, reports of continued chemical attacks continued to emerge.

Abdul Hamid Youssef lost his wife, his 11-month-old twins, two brothers, his cousin and many of his neighbours in the 4 April 2017 attack on Khan Sheikhoun.

He described the scene outside his home, seeing neighbours and family members suddenly drop to the ground.

“They were shivering, and foam was coming out of their mouths,” he said. “It was terrifying. That’s when I knew it was a chemical attack.”

After falling unconscious and being taken to hospital, he woke, asking about his wife and children.

“After about 15 minutes, they brought them all to me – dead. I lost the most precious people in my life.”

The OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mission concluded that a large number of people had been exposed to Sarin that day.

Sarin is considered 20 times as deadly as cyanide. As with all nerve agents, it inhibits the action of an enzyme which deactivates signals that cause human nerve cells to fire. The heart and other muscles – including those involved in breathing – spasm. Sufficient exposure can lead to death by asphyxiation within minutes.

The JIM also said it was confident that the Syrian government was responsible for the release of the Sarin in Khan Sheikhoun, with an aircraft alleged to have dropped a bomb on the town.

The images from Khan Sheikhoun prompted US President Donald Trump to order a missile strike on the Syrian Air Force base from where Western powers believed the aircraft that attacked the town took off.

President Assad said the incident in Khan Sheikhoun was fabricated, while Russia said the Syrian Air Force bombed a “terrorist ammunition depot” that was full of chemical weapons, inadvertently releasing a toxic cloud.

But Stefan Mogl, a member of the OPCW team that investigated the attack, said he found evidence that the Sarin used in Khan Sheikhoun belonged to the Syrian government.

There was a “clear match” between the Sarin and the samples brought back from Syria in 2014 by the OPCW team eliminating the country’s stockpile, he said.

The JIM report said the Sarin identified in the samples taken from Khan Sheikhoun was most likely to have been made with a precursor chemical – methylphosphonyl difluoride (DF) – from Syria’s original stockpile.

“It means that not everything was removed,” Mr Mogl said.

Mr Tangaere, who oversaw the OPCW’s elimination of Syria’s chemical stockpile, said: “I can only assume that that material wasn’t part of what was declared and wasn’t at the site that we were at.”

“The reality is, under our mandate all we could do was verify what we’d been told was there. There was a separate process to investigate potential gaps in the declaration.”

But what of the other 105 reported attacks mapped by the BBC team? Who is believed to have been behind those?

The JIM concluded that two attacks involving the blister agent sulphur mustard were carried out by the jihadist group Islamic State. There is evidence suggesting IS carried out three other reported attacks, according to the BBC’s data.

The JIM and OPCW have so far not concluded that any opposition armed groups other than IS have carried out a chemical attack. The BBC’s investigation also found no credible evidence to suggest otherwise.

However, the Syrian government and Russia have accused opposition fighters of using chemical weapons on a number of occasions and have reported them to the OPCW, who have investigated the allegations. Opposition armed factions have denied using chemical weapons.

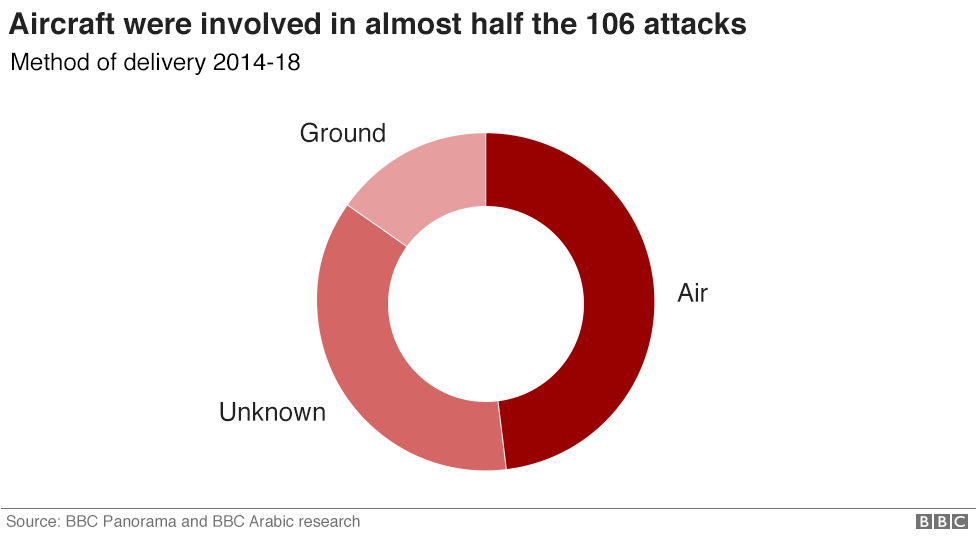

The available evidence, including video, photographs and eyewitness testimony, suggests that at least 51 of the 106 reported attacks were launched from the air. The BBC believes all the air-launched attacks were carried out by Syrian government forces.

Although Russian aircraft have conducted thousands of strikes in support of Mr Assad since 2015, UN human rights experts on the Commission of Inquiry have said there are no indications that Russian forces have ever used chemical weapons in the Syria.

The OPCW has likewise found no evidence that opposition armed groups had the capability to mount air attacks in the cases it has investigated.

Tobias Schneider of the Global Public Policy Institute has also investigated whether the opposition could have staged any air-launched chemical attacks and concluded that they could not. “The Assad regime is the only actor deploying chemical weapons by air,” he said.

Dr Lina Khatib, head of the Middle East and North Africa programme at Chatham House, said: “The majority of chemical weapons attacks that we have seen in Syria seem to follow a pattern that indicates that they were the work of the regime and its allies, and not other groups in Syria.”

“Sometimes the regime uses chemical weapons when it doesn’t have the military capacity to take an area back using conventional weapons,” she added.

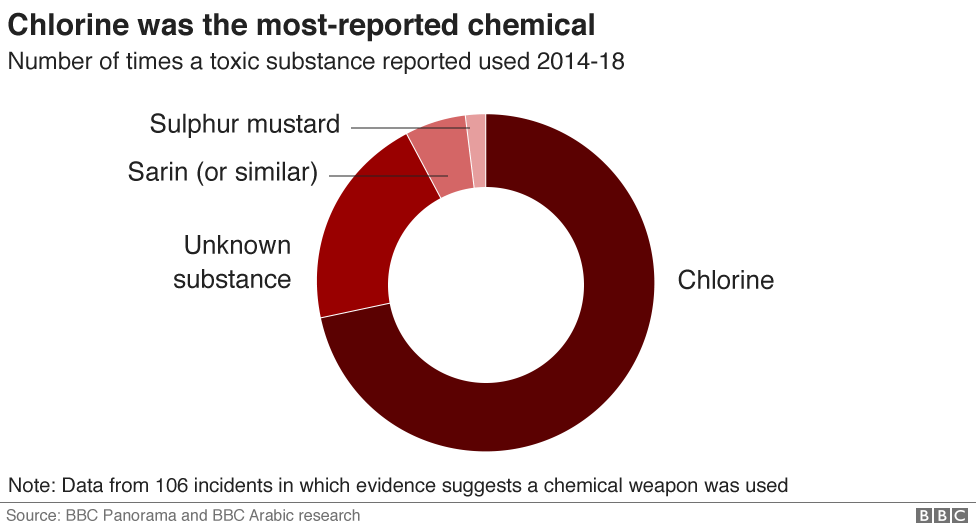

Sarin was used in the deadliest of the 106 reported attacks – at Khan Sheikhoun – but the evidence suggests that the most commonly used toxic chemical was chlorine.

Chlorine is what is known as a “dual-use” chemical. It has many legitimate peaceful civilian uses, but its use as a weapon is banned by the CWC.

Chlorine is thought to have been used in 79 of the 106 reported attacks, according to the BBC’s data. The OPCW and JIM have determined that chlorine is likely to have been used as a weapon in 15 of the cases they have investigated.

Experts say it is notoriously difficult to prove the use of chlorine in an attack because its volatility means it evaporates and disperses quickly.

“If you go to a site where a chlorine attack has happened, it’s almost impossible to get physical evidence from the environment – unless you’re there within a very short period of time,” said Mr Tangaere, the former OPCW inspector.

“In that sense, being able to use it leaving virtually no evidence behind, you can see why it has happened many, many times over.”

3. The use of chemical weapons appears to be strategic

Plotting the timings and locations of the 106 reported chemical attacks appears to reveal a pattern in how they have been used.

Many of the reported attacks occurred in clusters in and around the same areas and at around the same times. These clusters coincided with government offensives – in Hama and Idlib in 2014, in Idlib in 2015, in Aleppo city at the end of 2016, and in the Eastern Ghouta in early 2018.

“Chemical weapons are used whenever the regime wants to send a strong message to a local population that their presence is not desirable,” said Chatham House’s Dr Khatib.

“In addition to chemical weapons being the ultimate punishment, instilling fear in people, they are also cheap and convenient for the regime at a time when its military capacity has decreased because of the conflict.”

“There’s nothing that scares people more than chemical weapons, and whenever chemical weapons have been used, residents have fled those areas and, more often than not, not come back.”

Aleppo, a city fought over for several years, appears to be one of the locations where such a strategy has been employed.

Opposition fighters and civilians were trapped in a besieged enclave in the east as the government launched its final offensive to regain full control of the city.

Opposition-held areas first came under heavy bombardment with conventional munitions. Then came a series of reported chemical attacks that are said to have caused hundreds of casualties. Aleppo soon fell to the government, and people were displaced to other opposition-held areas.

“The pattern that we are witnessing is that the regime uses chemical weapons in areas that it regards as strategic for its own purposes,” said Dr Khatib.

“[The] final stage of taking these areas back seems to be using chemical weapons to just make the local population flee.”

From late November to December 2016, in the final weeks of the government’s assault on eastern Aleppo, there were 11 reported chlorine attacks. Five of them were in the last two days of the offensive, before opposition fighters and supporters surrendered and agreed to be evacuated.

Abu Jaafar, who worked for the Syrian opposition as a forensic scientist, was in Aleppo during the last days of the siege. He examined the bodies of many of the victims of alleged chemical attacks.

“I went to the morgue and a strong smell of chlorine emanated from the bodies,” he said. “When I inspected them, I saw clear marks of suffocation due to chlorine.”

The use of chlorine had a devastating effect, he said.

“The gas suffocates people – spreading panic and terror,” he said. “There were warplanes and helicopters in the sky all the time, as well as artillery shelling. But what left the biggest impact was chemical weapons.”

When liquid chlorine is released, it quickly turns into a gas. The gas is heavier than air and will sink to low-lying areas. People hiding in basements or underground bomb shelters are therefore particularly vulnerable to exposure.

When chlorine gas comes into contact with moist tissues such as the eyes, throats and lungs, an acid is produced that can damage those tissues. When inhaled, chlorine causes air sacs in the lungs to secrete fluid, essentially drowning those affected.

“If they go up, they get bombed by rockets. If they go down, they get killed by chlorine. People were hysterical,” said Abu Jaafar.

The Syrian government has said it has never used chlorine as a weapon. But all 11 of the reported attacks in Aleppo came from the air and occurred in opposition-held areas, according to the BBC’s data.

More than 120,000 civilians left Aleppo in the final weeks of the battle for the city, according to organisations on the ground. It was a turning point in the civil war.

A similar pattern of reported chemical weapons use can be seen in the data from the Eastern Ghouta – the opposition’s final stronghold near Damascus.

A number of attacks were reported in opposition-held towns in the region between January and April 2018.

Maps show how the incidents coincided with the loss of opposition territory.

Douma, the biggest town in the Eastern Ghouta, was the target of four reported chemical attacks over four months, as pro-government forces intensified their aerial bombardment before launching a ground offensive.

The last – and deadliest, according to medics and rescue workers – incident took place on 7 April, when a yellow industrial gas cylinder was reportedly dropped onto the balcony of a block of flats. The opposition’s surrender came a day later.

Videos published by pro-opposition activists showed what they said were the bodies of more than 30 children, women and men who had been sheltering downstairs in the basement of the block of flats.

Yasser al-Domani, an activist who visited the scene that night, said the people who died had foam around their mouths and appeared to have chemical burns.

Another video from a nearby building shows the bodies of the same children found dead in the block of flats wearing the same clothes, with the same burns, lined up for identification.

The BBC spoke to 18 people, who all insist they saw bodies being taken from the block of flats to the hospital.

Two days after the reported attack, Russian military specialists visited the block of flats and said they found no traces of chlorine or any other chemical agents. The Russian government said the incident had been staged by the opposition with the help of the UK – a charge the British government dismissed as “grotesque and absurd”.

An OPCW Fact-Finding Mission team visited the scene almost two weeks later and took samples from the gas cylinder on the balcony. In July, it reported that “various chlorinated organic chemicals” were found in the samples, along with residues of explosive.

The FFM is still working to establish the significance of the results, but Western powers are convinced the people who died were exposed to chlorine.

A week after the incident in Douma, the US, UK and France carried out air strikes on three sites they said were “specifically associated with the Syrian regime’s chemical weapons programme”.

The Western strikes took place hours before the Syrian military declared the Eastern Ghouta free of opposition fighters, by which time some 140,000 people had fled their homes and up to 50,000 had been evacuated to opposition-held territory in the north of the country.

“I saw the amount of destruction, the people crying, bidding farewell to their homes or children. People’s miserable, exhausted faces, it was really painful. I can’t forget it. People in the end said they’d had enough,” said Manual Jaradeh, who was living in Douma with her husband and son.

The Syrian government would not answer the BBC’s questions about the allegations that it has used chemical weapons. It refused to allow the Panorama team to travel to Damascus, examine the site of the reported attack in Douma, and turned down interview requests.

When asked whether the international community had failed the Syrian people, former OPCW inspector Julian Tangaere said: “Yes, I think it has.

“It was a life and death struggle for the Assad regime. You know, there was certainly no turning back. I can understand that.

“But the methods used, and the barbarity of some of what’s happened has… well, it’s beyond comprehension. It’s horrifying.”

So has President Assad got away with it? Karen Pierce, the UK’s ambassador to the UN, thinks not.

“There is evidence being collected,” she said. “One day there will be justice. We will do our best to try to bring that about and hasten it.”

Panorama: Syria’s Chemical War will be broadcast in the UK on Monday 15 October on BBC One at 20:30. It will be available afterwards on the BBC iPlayer. It will also be broadcast on BBC Arabic on Tuesday 23 October at 19:05 GMT.

Credits: Producers Alys Cummings and Kate Mead. Online production David Gritten, Lucy Rodgers, Gerry Fletcher, Daniel Dunford and Nassos Stylianou.

Source: Read Full Article