How ‘The Emp’s’ clothing empire went from riches to rags

Even 10 years ago it was impossible to think that Sir Philip Green’s retailing career would be ending in the way it appears to be.

The tycoon was the undisputed king of the high street, owner of a vast and profitable retail empire that straddled the BHS department store chain and Arcadia, owner of storied fashion chains such as Topshop, Topman, Miss Selfridge and Dorothy Perkins.

His stature was such that Goldman Sachs, one of the most powerful banks in Wall Street and the City, was prepared to back him in an ultimately unsuccessful takeover bid for the once-mighty Marks & Spencer.

At its height, his stable of businesses accounted for around 12% of the UK’s clothing market, with three in every five British women estimated to own at least one item of clothing bought from his shops. More than 40,000 people worked for him.

This dominance of retailing meant some competitors regarded him as even greater than a king.

Mike Ashley, the retail tycoon who in many ways has gone on to eclipse Sir Philip, even nicknamed him “The Emp” – short for emperor.

Sir Philip enjoyed a truly staggering lifestyle derived from the profits of these businesses, most famously the £100m 295ft-long Lionheart, one of three yachts he was reported to own, which boasted its own swimming pool and helipad.

Other rich man’s toys included a helicopter and a Gulfstream G550 jet.

As glitzy were his parties.

Sir Philip flew more than 200 guests to Cyprus for his 50th birthday celebrations in 2002, at which Rod Stewart and Tom Jones performed, while his 55th birthday party in the Maldives, where performers included George Michael and Jennifer Lopez, cost a reputed £20m.

Performers at his son Brandon’s £4m bar mitzvah in the South of France, meanwhile, included Beyonce.

His party guests included the former US president Bill Clinton.

The lifestyle was funded by a series of pay-outs that began with a £164.5m dividend from BHS in April 2002.

The most famous, though, came when Sir Philip and his wife Tina banked a near-£1.2bn dividend from Arcadia, which they had bought three years earlier for £850m.

Other payments, worth hundreds of millions, also flowed in from rental payments from the stores.

In 2007, just as the financial crisis was getting under way, Sir Philip and Lady Tina’s overall wealth was put by the Sunday Times Rich List at £4.7bn.

By then, the consummate networker had been knighted in the 2006 Birthday Honours, having been nominated by Tony Blair for services to retail.

When the coalition government was formed, in 2010, Sir Philip was asked by David Cameron to carry out a review of government spending and procurement.

It is sometimes claimed that, around that time, Sir Philip began to lose interest in the business.

That is only partly true.

Sir Philip was stung by his failure in 2004 to snare Marks & Spencer and by consistent carping by some critics that he was merely a shrewd asset trader rather than someone capable of building businesses.

It drove him, in the years immediately after that, to prove to the outside world that he was capable of developing and growing assets rather than just buying and selling them.

Under his ownership, supported by his talented brand director Jane Shepherdson, Topshop looked for a while like a British fashion business capable of conquering the world.

Sir Philip’s friend Kate Moss was brought on board as a designer.

Ms Moss was also on hand when, in April 2009, Topshop opened a 25,000 square foot store in Manhattan’s trendy SoHo district.

The store in the Big Apple was followed by openings in Los Angeles, Atlanta, Chicago, Houston, San Diego and Miami and, in 2012, the US private equity firm Leonard Green paid £350m for a stake in Topshop and Topman.

It was a transaction that led to speculation Sir Philip could take another tilt at M&S.

Looking back, though, it was probably the moment Sir Philip’s retail empire was at the height of its powers.

Denuded of investment and stores, some of which had been sold off over the preceding decade to buyers such as Monsoon, BHS found the going tough.

The whole business was eventually offloaded in 2015 for £1 to the serial – and now jailed – bankrupt Dominic Chappell in a trade that turned round and bit Sir Philip.

BHS, itself looted by Mr Chappell, swiftly collapsed.

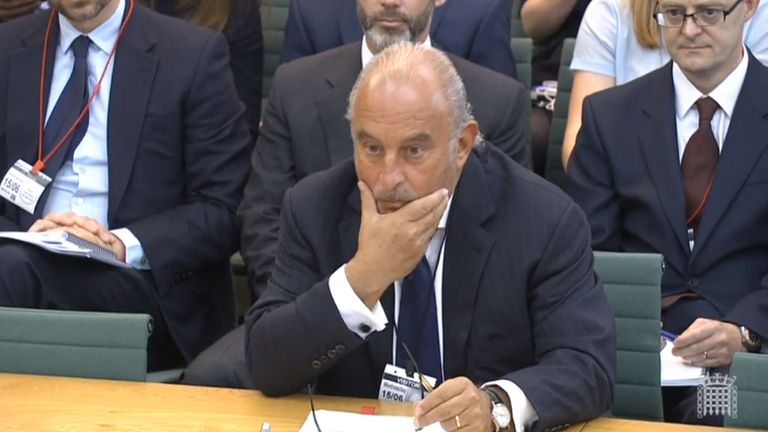

The following year saw Sir Philip hauled before MPs and dubbed the “unacceptable face of capitalism”.

In 2017, amid calls for him to be stripped of his knighthood, Sir Philip reached a deal with the Pensions Regulator in which he paid £363m in cash to plug the gap in the BHS pension scheme.

By now, though, Arcadia was struggling.

The move from physical to online retailing had left it with too many stores and, in addition, the business had been losing market share to fast-fashion rivals such as Primark, Asos and Boohoo.

Leonard Green sold back its stake in Topshop and Topman for a nominal $1 in April 2019 and shortly afterwards all 11 of the group’s US stores were closed.

Losses at Topshop, previously the jewel in the crown, ballooned to just under £500m in the year to September 2018.

As his businesses felt the heat, so too did Sir Philip, who was accused by the Daily Telegraph in February 2019 of inappropriate behaviour in the workplace.

The allegations included groping a female employee and using racially insensitive language.

Shortly afterwards, the businesswoman Karren Brady resigned as chair of Arcadia’s parent company, Taveta Investments.

Asked by Sky News in January this year how she had squared her feminist credentials with working for Sir Philip, Baroness Brady replied: “Well, I didn’t square them because I resigned. I think that says all it needs to say.”

Then came COVID-19.

As its shops were forced to close during the lockdown, Arcadia put its 14,500 employees on furlough, while 500 head office staff were made redundant.

The second lockdown in November was a crushing blow and, earlier this month, Sky News reported that the company was seeking a £30m loan.

This does not appear forthcoming and explains why the business may now be tipped into administration – with questions again being asked about how large a deficit exists in the pension scheme.

Sir Philip is thought unlikely to seek to buy assets back from the administrator which would effectively, bring down the curtain on a career that began 50 years ago as a “job buyer” in London’s rough and tough rag trade in the 1960s and which, in the early 1980s, saw Sir Philip ostracised by the City in a way that left him with a lifelong mistrust of the Square Mile.

It is a career that has had many spectacular twists and turns and that, had it been offered to a publisher, would have been declined as too fantastic too believe.

And it is a career that this proud man would not have wanted to see end in this way.

Source: Read Full Article