Home » Australasia »

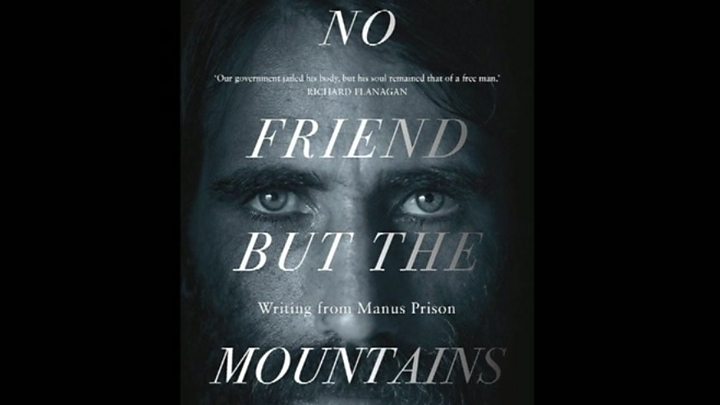

Refugee’s WhatsApp-written book wins prize

An asylum seeker and journalist detained for years by Australia on an island in the Pacific has been awarded the country’s richest literary prize.

Behrouz Boochani, an Iranian Kurd, wrote No Friend But the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison by text message from inside a detention centre.

It won the 2019 Victorian Prize for Literature, worth A$100,000 (£55,000).

Boochani remains on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island and is not allowed to enter Australia.

The controversial detention centre in which he was held was closed in late 2017. He – and hundreds of others – have since been moved to alternative accommodation.

Australia has a strict policy on any asylum seekers who arrive by boat, vowing that they will never be resettled in Australia, even if found to be genuine refugees. It says its policies are necessary to deter dangerous attempts to reach the country by sea.

Alongside the prize for literature, No Friend But the Mountains also won the Prize for Non-Fiction at the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, worth A$25,000.

Speaking to the BBC from Manus Island on a night when fellow writers who won awards were celebrating in Melbourne, Boochani said the prizes gave him “a very paradoxical feeling”.

“In some ways I am very happy because we are able to get attention to this plight and you know many people have become aware of this situation, which is great… But on the other side I feel that I don’t have the right to have celebration – because I have many friends here who are suffering in this place.

“[The] first thing for us is to get freedom and get off from this island and start a new life.”

The book was written in Farsi during the years in which Boochani was held in the now-closed detention centre, mostly through WhatsApp messages sent to the translator, Omid Tofighian.

“WhatsApp is like my office,” he said. “I did not write on paper because at that time the guards each week or each month would attack our room and search our property. I was worried I might lose my writing, so it was better for me to write it and just send it out.”

Boochani, who was first detained in 2013 after arriving by boat from South East Asia, has become the most well-known voice from inside Australia’s controversial offshore detention system.

He writes regularly for the UK’s Guardian newspaper, tweets prolifically about life on Manus and spars with online defenders of Australia’s tough policies. He has even shot and co-directed a documentary – Chauka, Please Tell Us The Time – from detention. Again, he used his phone.

Last year, the US agreed to resettle some of the refugees from the offshore detention centre on Manus and the island nation of Nauru. More than 100 refugees have since been relocated, but Boochani is still waiting for further information after an interview with US officials a few months ago.

He has been granted refugee status in Papua New Guinea but like many of the refugees does not want to stay there.

He said he decided to flee Iran because of problems with the authorities over his journalism: “I didn’t want to go to prison in Iran so I left and when I got to Australia they put me in this prison for years.”

Judges of the literature prize described his book as “a stunning work of art and critical theory which evades simple description”.

“Distinctive narrative formations are used, from critical analysis to thick description to poetry to dystopian surrealism,” they said. “The writing is beautiful and precise, blending literary traditions emanating from across the world, but particularly from within Kurdish practices.”

The entry guidelines for the Victorian Prize for Literature stipulate that writers must be Australian citizens or permanent residents. However the Wheeler Centre, which administers the literature awards, accepted the recommendation of its judges and made an exception for Boochani’s book.

Australia’s refugee policies have been widely covered by the world’s press and criticised by the UN and global human rights groups, although some European politicians have praised them.

But Boochani wants readers of his book to understand what he says has been a “systematic” attempt to strip refugees and asylum seekers of their “identity, humanity and individuality”.

“We are not angels and we are not evil,” he said. “We are humans, simple humans, we are innocent people.”

An excerpt from No Friends But The Mountains

Days without any plans /

Lost and disoriented /

Minds still caught up in the waves of the ocean /

Searching for peace of mind on new plains /

But the prison’s plains are like a corridor leading to a fighters’ gym /

And the smell of warm sweat everywhere is driving everyone insane.

One month has passed since I was exiled to Manus. I am a piece of meat thrown into an unknown land; a prison of filth and heat. I dwell among a sea of people with faces stained and shaped by anger, faces scarred with hostility. Every week, one or two planes land in the island’s wreck of an airport and throngs of people disembark. Hours later, they are tossed into the prison among the deafening ruckus of displaced people, like sheep to a slaughterhouse.

Source: Read Full Article