Home » Australasia »

How cartoons saved my life

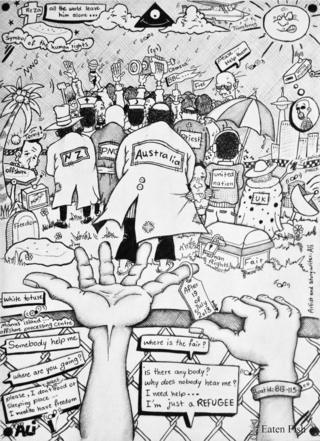

Cartoonist Ali Dorani fled Iran at the age of 21 before becoming trapped in Australia’s controversial Manus Island detention camp for four years – but things changed after his artwork was posted online.

Here’s his story – in his own words and drawings.

In 2013, I left Iran. I can’t tell you why because it might affect my family’s safety – but I knew my life was in danger.

I stayed in Indonesia for 40 days, and tried to get to Australia – I knew Australia was the best way for me to get to safety.

A people smuggler told me he could get us to Australia by boat.

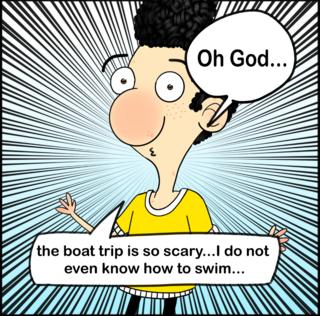

When I saw the boat, I was afraid I would die. It was a fishing boat, not really well maintained, and there were about 150 of us. And I can’t swim.

When the time came to get on the boat, I told myself: “This is it. If anything happens to that weak boat, I’m going to die.”

The journey took us 52 hours – it was raining and the ocean wasn’t normal. It was so scary.

The Australian navy intercepted us and took us to Christmas Island – a detention centre where Australia keeps asylum seekers who arrive by boat.

I had suffered from OCD [Obsessive Compulsive Disorder] for a number of years – but it got worse on Christmas Island.

I liked to keep my surroundings clean at all times – but I couldn’t control it anymore because I was in a room with several other people.

At one point, I tried to wash my dictionary in the shower because I felt it was dirty. I kept telling myself I was going crazy – I was shaking and getting so nervous.

Doctors at the medical centre told me I had to take medication, or find some strategies to deal with my OCD.

I didn’t want to take medication because I was worried the Australian government would call me crazy and blacklist me from entering.

But when I went back to my room I slowly remembered that I had a talent for drawing. So I started drawing again to deal with my OCD.

I’ve been drawing since I was five years old – it’s one of my earliest memories.

I’d stopped a few years before I fled Iran, because I was so busy with work and life – but now I felt so sick that I started drawing again.

I didn’t always have something to draw on. We could request materials from immigration officers, but they wouldn’t always give us paper and pencils.

So I had to steal paper – I’d go into language classes, and take blank papers when the teacher was looking the other way.

Because I only had a limited supply of paper I couldn’t make mistakes in my drawings – that also helped me improve my skills.

Drawing actually didn’t help my OCD, which was still getting worse every day.

But I started showing my drawings to other detainees, and some of the immigration officers, and people got interested in my cartoons.

I drew about my life there – what happened when I lined up to get food, what it was like using dirty public toilets.

I remember the first time I realised people took my work seriously.

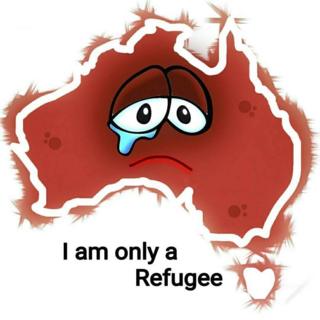

I drew a map of Australia on a white T-shirt, with two eyes crying, and the words “I am only a refugee”.

Two immigration officers asked me why I drew on my T-shirt – they saw the drawing as a protest.

I hadn’t meant it as a protest – I had no idea my drawing would be taken that seriously – but it made me realise that my drawings could affect others.

So I kept cartooning – drawing diaries about daily life in the detention centre – and getting lots of positive and negative comments.

I was afraid that my drawings could affect my asylum application – but I also thought there could be nothing worse than being kept in a detention centre. I was depressed and my OCD was really difficult – so I thought I was already in a nightmare, and there was nothing else to be afraid of.

In fact, Christmas Island was much nicer than where I went next.

I was moved to Manus Island after six months, in January 2014. They handcuffed us and I had five security officers around me.

It was my first time in a tropical country – it was really hot and it was difficult to breathe.

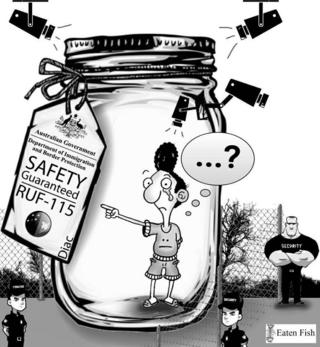

It didn’t look like the detention centre on Christmas Island. It looked like somewhere where you would keep chickens, pigs or sheep.

We had tents, dirty rooms, dirty toilets, and horrible showers. There were hundreds of people crammed in a small camp.

Some of the guards tried to reassure me – they could see the shock on my face. They told me: “Don’t worry, everything is going to be fine.”

I felt I didn’t have any choices left – I couldn’t go home, couldn’t stay in Australia, and didn’t want to kill myself. I felt like a dead body who was forcing himself to stay alive.

What is Australia’s asylum policy?

Australia asylum: Why is it controversial?

The island where children have given up on life

Manus Island: Australia’s Guantanamo?

I didn’t have any pencils or paper when I arrived on Manus Island – they took away my pencils when I left Christmas Island – although I could keep my drawings.

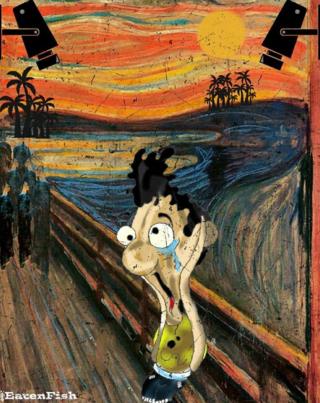

At first, I didn’t want to draw. When you’re forced to live in a place, but don’t know why you are there, or when it is going to end, you lose hope, you lose all motivation, and this, combined with the weather, the sun, the mosquitoes – all help to destroy you inside.

An incident happened on 17 February 2014 – some of the locals attacked the camp, smashing everything and beating people up. They killed one of the refugees as well.

For about a month after that, we didn’t have access to much – no proper food, or services.

Then another company came to run the camp – they improved the dining room and brought different activities in the camp, including English classes and drawing activities.

I started drawing again, documenting life at the camp. I also drew the mosquitoes, the sun and the rain.

I chose EatenFish as my penname, because I was caught from the sea like a fish, “eaten” (processed) at an Australian detention camp, and then “thrown away” on Manus Island (the same way you throw fish bones into a rubbish bin).

In some of my pictures, I added graves for the refugees who had died.

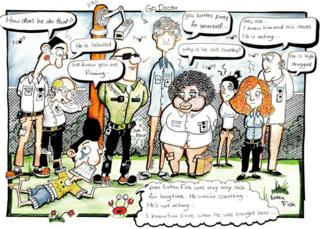

Sexual harassment and sexual assault were serious problems on Manus Island.

It wasn’t only me suffering from this – there were a lot of young people like me suffering.

I witnessed it a lot, but I couldn’t do anything about it because I was already under too much pressure, suffering from OCD, panic attacks and anxiety.

We didn’t have access to the internet at this time, and I didn’t have any hope of sharing my drawings with the outside world.

However, the Australian government eventually decided we would each be allowed to use the internet for 45 minutes every week.

The connection was really slow, and was barely strong enough to get onto Facebook – but I started logging on, joining Australian humanitarian groups, and sending friend requests to each of the members.

I did that for 1.5 years – sending messages to thousands of strangers. No one replied.

However, it turns out a lot of the Australian workers and immigration officials at the camp were talking about my drawings, even when they got home.

An activist – Janet Galbraith – heard about my drawings and contacted me on Facebook – she said she was starting a gallery in Melbourne, and wanted to display one of my drawings.

It wasn’t easy sending her my pictures because we didn’t have access to a scanner, or cameras.

A few people had secretly kept their mobile phones, although most of the cameras weren’t very high-quality.

Eventually, I managed to secretly take a photo of my drawing using a mobile phone, and sent it to her.

After Janet displayed the photo in the gallery, one man working on Manus Island saw the picture, and told Janet he knew me and could help get my drawings out.

He was working for the government so I couldn’t really trust him, but at the same time I didn’t have many other choices.

He took photos of my drawings with his iPad and sent them to Janet – and then my drawings started getting published by news organisations.

In 2015, many of us went on hunger strike against Australia’s policy, and conditions at the camp.

I ended up getting really sick – I had panic attacks, with muscle spasms, for almost 40 minutes. Sometimes I had panic attacks three times a day.

The doctors put me on different forms of medication, but there were days when I’d wake up and not be able to remember where I used to live or who I was. I was kept in isolation for almost one month.

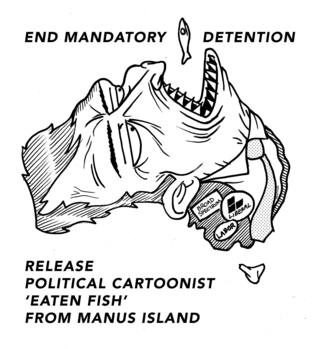

After I got out of isolation, I contacted Janet again, and explained what happened to me. I also got in touch with Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI), and was put in touch with the Guardian cartoonist First Dog on the Moon.

The Guardian started publishing my work, and in 2016, CRNI gave me their Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award.

That got me a lot of publicity – but I didn’t really realise it at the time, because my internet access was so limited.

I would hear from people that I’d been published, or get sent links to my work – but I’d have to wait to use the internet room each week, and often the connection wouldn’t work well.

I didn’t think the publicity would help me – I saw it as a chance to show my drawings to Australians, but I didn’t see how it would get me out of detention.

In 2016, artists around the world started drawing cartoons to show their support for me.

When I was a child, one of my wishes was to become a cartoonist, because I would read cartoons in magazines and wish my cartoons could be published too.

So when I saw that all these cartoonists that I used to worship and see in magazines had drawn cartoons to save me, it was a big honour for me.

Cartoonists who had been published in the Washington Post, New Yorker, and New York Times, all drew cartoons about EatenFish.

I felt extremely grateful.

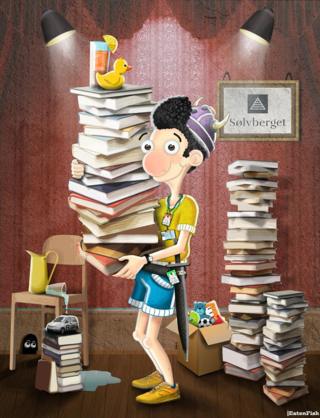

The International Cities of Refuge Network (Icorn), a Norwegian organisation that helps writers and artists, also started working on my case.

I didn’t know anything about Icorn at the time – Janet just told me they were looking at my case – but I didn’t believe they’d be able to help me.

I went on hunger strike in late 2016, because I was being harassed by other detainees, and workers on Manus Island.

The strike lasted around 22 days. I was already sick, but felt I didn’t have any other choice – and by the end of the strike I weighed 43 kilos.

After my hunger strike, I was moved to a hospital in Papua New Guinea for almost three months. While I was there, I got a message from Norway’s immigration department, welcoming me.

I couldn’t believe it.

When I got onto the plane to Norway, Janet was there with me. I couldn’t stop crying for a few hours – I don’t normally cry easily, but this time I couldn’t stop. All my years in detention came up in front of my eyes – and I couldn’t believe that it was the end.

I was so excited and so scared when I arrived in Norway. A few people came to the airport to pick me up, showed me where I would be living, and told me about the support I’d get.

It wasn’t easy at first. For the first six to eight months I was in a deep depression – even stronger than the one I had on Manus Island. It still affects me now.

But I got good support from the government, and help from refugee organisations, especially Icorn. I don’t think it’s possible to get better support than what I got in Norway.

Icorn gave me an office in a public library in Stavanger, so I can work on my projects. A lot of children visit the library, and sometimes I hold drawing courses.

I also go to different schools to talk about Australia’s refugee policy. Icorn also helps me financially, and helps me interact with different artists around Norway.

A lot of people ask me if I feel happy now. It’s complicated.

I didn’t choose to come here – I didn’t have any other choices. But now, I love the city that I live in.

I think Norway has the best support and services for refugees – there are detention camps for asylum seekers, but they are not locked in – they can go out, interact with people, and see children playing in parks.

I always say that art saved me – it helped the Norwegian government find out about my situation.

While I was in detention on Christmas Island, and Manus Island, lots of people liked my drawings but told me they wouldn’t get me anywhere. Some of the detainees asked me: “What are you going to achieve with this? You can’t help get us out of here with these drawings.”

But now, I think I have the right to say that art actually saved me. I started drawing cartoons in detention, to try and control my illness, and eventually, cartoons saved my life. I genuinely believe that art can help bring peace, and that I have to look after my art and respect that.

All pictures subject to copyright.

Source: Read Full Article