Home » Australasia »

Does the world need any more large zoos?

Sydney’s first new major zoo in more than 100 years will open on Saturday. With such debate about animal welfare these days, can zoos still be a force for good? Gary Nunn reports from Sydney.

Zoos have evolved significantly since they were first created.

Their original purpose was braggadocio: a way for the wealthy to display their power in private collections. Later, they helped with science research. Then they became tourist attractions the public would pay to view. It wasn’t until the 1970s onwards that conservation emerged as a priority.

Some animal welfare academics argue that zoo enclosures have vastly improved in the past 50 years – but dissenters remain impassioned and vocal.

One academic told the BBC: “We don’t need more zoos.”

Sydney Zoo, about 40km (25 miles) west of the centre, is marketing itself on attractions such as Australia’s largest reptile and nocturnal house.

Among the animals on show will be African lions, Sumatran tigers, cheetahs and chimps as well as native Australian wildlife.

“My father had the original idea in the ’80s whilst managing Sydney Aquarium,” says Jake Burgess, the managing director of the new zoo. “Together we refreshed it after finding the perfect plot of land in western Sydney.”

Its main rival is Taronga Zoo, a hugely popular tourist attraction which opened in 1916 near the city centre. With temperatures hotter away from the coast, the Sydney Zoo has invested in climate control technology both to encourage guests to visit and to keep animals cool.

“Many exhibits feature air conditioned back-of-house spaces which allow animals to rest comfortably, as well as misting stations and shade structures,” Mr Burgess says.

The anti-zoo arguments

The new zoo says animal welfare is “the primary consideration”. Nevertheless, ardent opponents remain.

“My simple response would be: we don’t need more zoos,” said Marc Bekoff, professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado and an outspoken critic.

Prof Bekoff’s research into the sentience of animals reported on the stress, fear and boredom animals experience when confined in claustrophobic zoo enclosures that can be one millionth the size of their natural ranges.

“They’ll feel the exact same emotions as companion animals – dogs and cats – if they’re just kept locked up,” he says.

This is backed up by a study which found that elephants in zoos often endure stress and have significantly shorter life spans than wild elephants.

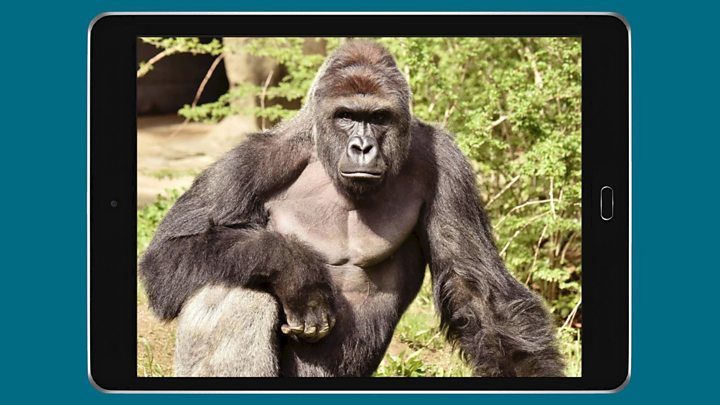

Then there are the horror-story incidents: Harambe the gorilla was shot and killed in 2016 after dragging a toddler who’d climbed into an enclosure at Cincinnati Zoo; Tilikum the orca killed trainer Dawn Brancheau at Sea World Orlando; London Zoo keeper Jim Robson was killed by an elephant in front of a packed crowd in 2001.

Ben Pearson, from World Animal Protection, says he has an additional concern: “What happens if this private zoo goes bankrupt? Zoos Victoria [in Melbourne] and Sydney’s Taronga Zoo are publicly funded so they’re able to to maintain high welfare standards.

“If Sydney Zoo goes bust, the elephant they shipped all the way from Dublin will likely have to be shipped back, adding to its distress.”

Animal rights group Peta has said the new zoo is “nothing to celebrate” and that “Australians passionate about wild animals” should donate to organisations supporting animals in the wild instead.

Where zoos are doing good

Sydney University’s David Phalen is considered a pragmatist on zoos. The veterinary science professor concedes that zoos will never replicate wild habitats, and has released studies showing captive cheetahs are more likely to develop arthritis.

But he adds: “When more countries are becoming increasingly urbanised, zoos make people more aware of the wider environment. They may watch David Attenborough, but that’s no comparison to actually seeing a tiger up close.”

The impact of this experience can encourage an enthusiasm for animal welfare and other things, such as boycotting products containing palm oil which destroy the habitats of animals like orangutans.

Many zoos put some profits into conservation. The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums encourages members to spend 10% of operational expenditure on conservation projects. Sydney Zoo is in the process of receiving accreditation.

Sydney’s 103-year-old Taronga Zoo is widely considered a leader in everything positive a zoo can be – promoting conservation, education, and animal welfare.

Nick Boyle leads a team of 66 people at the zoo who focus on animal welfare and conservation.

He names seven species that he says would be extinct without Taronga’s intervention: the Bellinger River turtle, the Lister’s gecko, the Christmas Island blue-tailed skink, the Northern Corroboree frog, the Southern Corroboree frog, the yellow-spotted bell frog, the Booroolong frog.

Mr Boyle lists several other actions by the zoo, including: “We rehabilitate about 50 marine turtles a year. Often they’re admitted for marine entanglement or ingestion of plastic – so we can show our visitors this to encourage them to make better choices around recycling and littering.”

What the priorities should be

So if a zoo is going to open, what can it learn from best practice?

Prof Phalen says Portland Zoo is one place leading innovation. “Their big cat enclosure has set up a contraption that throws mince balls in the air,” he says. When the big cats hear a click, they go into hunt mode. It keeps them engaged and reduces distressing boredom.”

Other zoos now use robots to clean enclosures so animals aren’t regularly transferred to small holding cages.

For zoo opponents like Prof Bekoff, stopping captive breeding and shipping animals around the world as “breeding machines” are among the bare minimums.

“Give the animals as much choice and control over their environment as possible, particularly with things like social groupings,” he says.

Taronga – which employs a behavioural expert to monitor animals and ensure their welfare – does have a breeding programme, but argues Australia’s location makes alternatives difficult.

“Australia is isolated from Europe and the US and has very strict bio-security parameters so it’s not impossible to participate in global breeding programmes, but it needs to be done right,” Mr Boyle says.

Australia’s newest zoo insists it’s taking this all on board.

“Our habitats have been designed with animal welfare as a priority,” says managing director Jake Burgess.

“We’ve used moats to create a sense of openness and space which improves animal welfare and guest experience.”

Sydney Zoo’s opening weekend had sold out well ahead of time, suggesting there’s no shortage of public interest in visiting such facilities.

But asked whether zoos are a good way of connecting people in cities to the welfare of wildlife in the bush, Prof Bekoff says there’s “little evidence they educate in a meaningful way”.

“People can get a good enough education watching wildlife TV shows. The lesson zoos teach? It’s OK keeping animals in cages.”

Source: Read Full Article