The dark side of Asia’s pop music industry

They are known as “idols” and their job is “to sell dreams”. For decades, the young pop stars of Japan and South Korea have been the envy of teenagers.

But behind the glamour, the lucrative industry is run by talent agencies with an iron fist. Two recent apologies by Japan’s popular band SMAP and Taiwanese star Chou Tzuyu have highlighted just how much power they have.

Both J-pop and K-pop – as Japanese and South Korean pop are known – are multi-million dollar industries yet most of their stars are on salary and do not earn very much.

They are also bound by strict rules on how to be idols. In Japan, for example, many are not allowed to date and getting married requires permission.

The “no dating” clause of the contracts has resulted in some idols being sued for breaking it, accused of damaging their reputations. Two years ago Minami Minegishi from popular girl band AKB48 shaved her head and wept in apology, after breaking management firm rules by spending a night with her boyfriend.

Manufactured boy or girl bands are nothing new, but Tokyo-based Asia Bureau Chief of Billboard Magazine Rob Schwartz says “it’s unheard of in the West for the agencies to control their personal lives”.

“It’s possibly comparable to the situation in the 1940s in the US when film studios had huge control over their movie stars but even then, they may have been encouraged not to date or marry but there was less coercion,” he added.

In South Korea, while stars can date and get married more openly than in Japan, the agencies still have a very hands-on approach to their daily lives.

“They are very concerned about how their talents are perceived, in part because of several infamous scandals in the 1990s,” said Mark Russell, an expert on the K-pop industry.

“If you go to the agency, every young trainee will give you a very polite bow and there are notices with the company rules on the wall to remind them how to behave.”

There is also speculation that some young stars are advised to undergo cosmetic surgery.

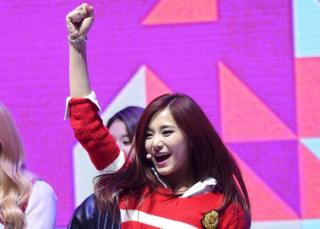

Discussing politics is one of many taboos – recently, waving a Taiwanese flag got Taiwanese star Chou Tzuyu, 16, into trouble as critics argued that she was supporting independence.

Her video apology was posted online by her South Korean agency, JYP Entertainment.

It denied coercing her to appease angered Chinese audiences, but Mr Russell believes there would have been a serious sit-down discussion about how the scandal was not just about her but about the whole company.

What the agency failed to realise, however, was how it may be perceived in other markets where K-pop is also popular. Her apology triggered an outcry in Taiwan where many considered it humiliating not just for the young star but for Taiwan.

“Korea puts strong emphasis on humility but it can come across as too extreme outside the country,” Mr Russell explained.

A few days later in neighbouring Japan, the members of the ageing boy band SMAP – all dressed in black – bowed deeply in a sombre apology on their weekly programme SMAPxSMAP.

Their sin was trying to leave their agency, Johnny & Associates.

The apology was not only addressed to their fans, for rumours that they were considering splitting up, but also to the founder of the agency, 84-year-old Johnny Kitagawa, one of the most powerful and controversial figures in Japan’s entertainment industry.

He has been recognised three times by Guinness World Record, once for the most singles produced by an individual. He was behind 232 Number 1 Singles between 1974 and 2010, just one small measure of the virtual monopoly he has had on the creation of Japanese boy bands.

Standing at the centre of the five members was Takuya Kimura, the only member who was going to stay with the agency. The other four were reportedly going to follow their long-time manager Michi Iijima who is believed to have fallen out with its founder’s sister and vice-president, Mary Kitagawa.

At the far left was Masahiro Nakai – the group’s leader who has usually been placed in the middle of the band. Such subtleties may be lost on many readers, but the symbolism is powerful for Japanese observers. The tabloid newspaper Nikkan Gendai headlined it: “Nakai’s public execution.”

Others saw the similarity between SMAP members and Japan’s so-called white collar salarymen, unable to disobey their employers.

The word “corporate slaves” started trending on social media and when Twitter went down for 15 minutes at around that time, Japanese fans speculated that it was traffic from SMAP that brought it down.

Fans also complained to the country’s media watchdog, citing power harassment.

But interestingly, mainstream media stayed away from the controversy and only reported the sense of relief that fans expressed at the news the band was staying together.

This led to accusations that they were afraid of criticising powerful Johnny & Associates as it represents many other popular talents.

The BBC approached Johnny & Associates about the controversy, but they declined to comment. South Korea’s JYP Entertainment also did not respond to requests for comment on the Chou Tzuyu incident.

“Journalists who work for mainstream Japanese media clearly understand what they’re allowed to and not allowed to write so they operate on self-censorship,” said Mr Schwartz from Billboard Magazine.

In South Korea, while there is no single talent management agency which has the same iron grip on media, K-pop expert Mr Russell says “there was a lot more mutual back-scratching between the agencies and media before”. The coverage of scandals has since changed, largely because of the liberating force of internet reaction on social media.

Like elsewhere in the world, the glamour of pop stardom is a huge appeal for Japanese and South Korean children.

But these latest incidents show that even among fans, there is a debate about how the reality of the industry is quite far from the dream that these idols are supposed to be selling.

Source: Read Full Article