Sweden: The West’s fixer in North Korea

When Australian student Alek Sigley went missing in North Korea last week, Canberra turned to a country more than 15,000km (9,320 miles) away for help.

The Scandinavian nation of Sweden has a long history of acting as diplomatic intermediary in the isolated dictatorship – a so-called “protecting power” for several Western nations.

On Thursday, it emerged that negotiations to free the 29-year-old had been successful. It’s still unclear why he was detained.

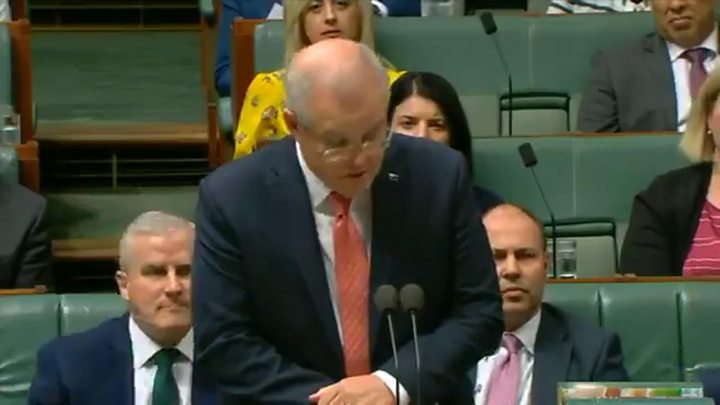

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison thanked Sweden for its help, expressing his “deepest gratitude to the Swedish authorities for their invaluable assistance.”

Australia, like most Western nations, doesn’t have its own embassy in the closed-off country. But Sweden does and has for nearly 50 years.

In fact it became first Western country to establish formal diplomatic relations with North Korea in 1973. The UK, in comparison, first sent an ambassador to North Korea only in 2002.

Negotiating the release of Mr Sigley – who studies Korean literature at Kim Il-sung University in Pyongyang – is not the first time Sweden has helped other countries with tricky diplomatic affairs.

It has in the past represented British interests in Iran when relations with Tehran have broken down, including in 1989 when Iran’s supreme leader issued a fatwa ordering Muslims to kill the novelist Salman Rushdie.

A history of neutrality

Stockholm’s special role is based on a long tradition of neutrality. This dates back to the early 19th Century, when Sweden took the position that it was best to be free of military alliances in peacetime so it could stay neutral if war broke out.

That meant that during the Cold War between the communist eastern and capitalist western blocs, Sweden tried to take a neutral middle position.

It similarly took a neutral position on the Korean peninsula. At the end of the Korean War in 1953, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission – comprised of Sweden, Switzerland, Poland and Czechoslovakia – was set up to oversee the armistice that ended the Korean war.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, North Korea expelled the Polish and Czechoslovakian observers.

“[But] the Swiss and Swedes [were] still there. This [caused] both countries to take a greater role in Korea than otherwise,” Fyodor Tertitskiy, an expert on North Korea, told the BBC.

Prisoner releases

Sweden’s role as an intermediary with Pyongyang has included handling consular affairs for the United States.

“Sweden has agreed with the US to represent the consular interest of [its] nationals in the DPRK,” former deputy head of mission at the Swedish Embassy in Pyongyang Martina Aberg Somogyi told specialist North Korea site NK News last year.

“If it comes to our attention that a US national is in need of support we will offer this to the best of our ability and work as hard we can to resolve that situation.”

Washington – like Canberra – has no North Korean embassy or consulate and Sweden acts as what is known in diplomatic parlance as a “protecting power”.

Ahead of the landmark Trump-Kim summit in Singapore in 2018, North Korea’s foreign minister even flew to Sweden for talks.

Sweden has also often helped with the release of US citizens held by the North.

The most high-profile recent case was that of US student Otto Warmbier, who was jailed in North Korea in 2016 after being accused of stealing a propaganda sign during an organised tour.

He spent 17 months in detention, and later died days after he was returned to the US in a coma.

Ms Somogyi said helping foreign citizens had “definitely been some of the most challenging work that me and my colleagues have engaged in on a professional but also personal level”.

Diplomatic life in Pyongyang

Sweden’s role in North Korea is not limited to helping Westerners in distress. It also performs other functions, such as following up on Swedish humanitarian assistance to North Korea and issuing visas to North Korean residents travelling to Europe’s Schengen area.

There are currently two Swedish diplomats based full-time in Pyongyang.

But those who have worked in the embassy say that there is still a lack of mutual understanding between North Koreans and Swedes.

“New initiatives and ideas are always met with deep suspicion,” Swedish diplomat August Borg told NK News in 2015.

“Even if we just want to visit a project that Sweden is financing, preparations need to be made a long time ahead.”

Source: Read Full Article