Singapore's largest active Covid-19 cluster: What went wrong at Changi Airport?

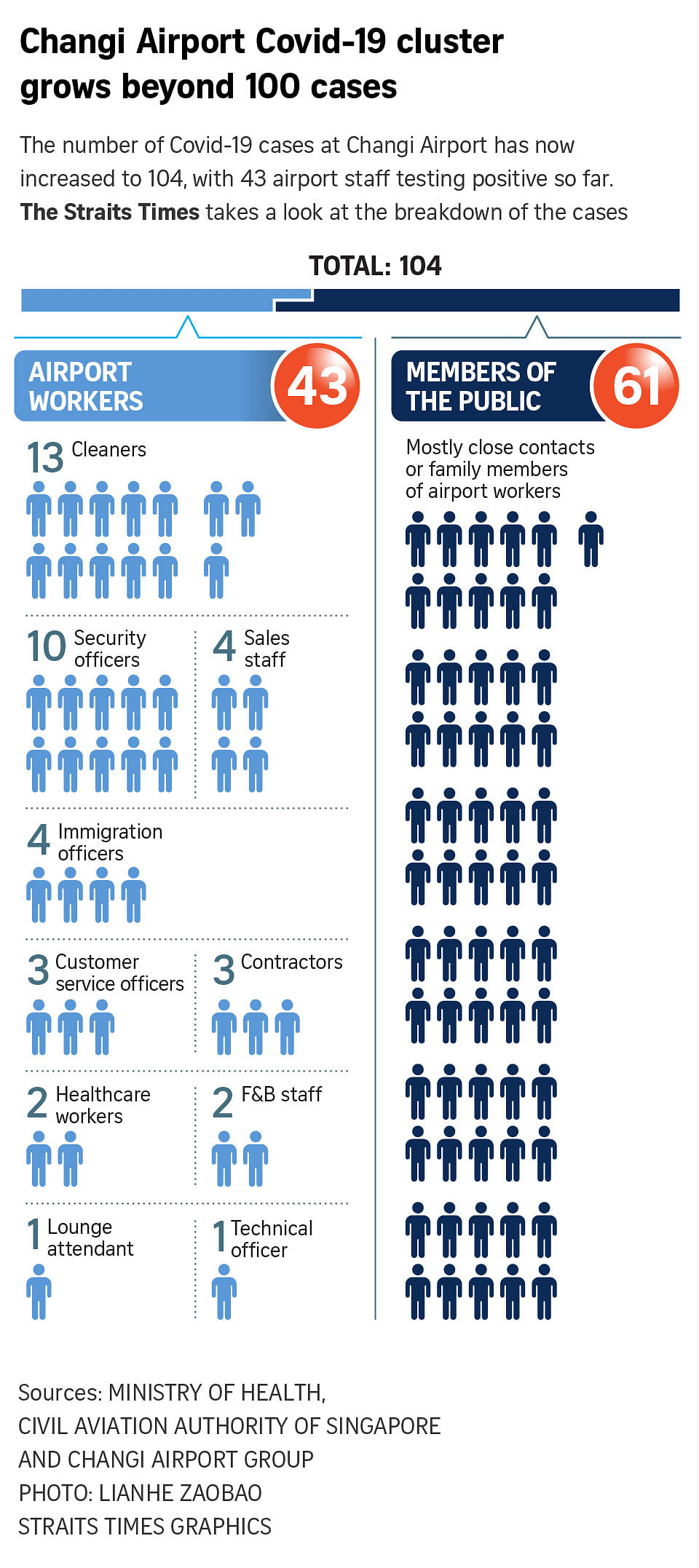

SINGAPORE – In less than a month, the Covid-19 cluster at Changi Airport has swelled to more than 100 people, including airport workers whose jobs did not require them to interact with passengers, family members of front-line staff and visitors.

It is now the largest active cluster in Singapore, and accounts for four of the 30 new community cases reported on Friday (May 21).

Stringent measures – including strict limits on social gatherings and proactive testing of airport staff – are currently in place to ring-fence the cluster and prevent further transmission in the wider community.

But how did Singapore land itself in this situation?

Border controls

In early April, Covid-19 cases in India began to rise, leading to questions being raised about whether Singapore should take pre-emptive measures to stop flights from the country.

On April 22, the country announced it would ban all long-term pass holders and short-term visitors who had travelled to India in the past 14 days. A week later, these restrictions were extended to four neighbouring countries: Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

But by then, the new, more transmissible B1617 strain had already made significant inroads here.

As an outward-looking country with a globalised economy, highly dependent on workers from abroad for several key industries, Singapore took “the strategic decision to remain open as long as possible”, noted Associate Professor Natasha Howard from the National University of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health.

It was therefore to be expected that some cases would be imported even with rigorous border control measures, given how differently the virus has been controlled in many countries, she said.

In other words, cutting off flights from high-risk countries would simply have delayed the inevitable, said Associate Professor Jeremy Lim, also from the Saw Swee Hock School.

Even so, this delay could have been crucial in “bolstering the bulwarks”, Prof Lim added. “Could we have closed off for a short period, to review and tighten our defences?”

Associate Professor Hsu Li Yang, vice-dean of global health at the school, also pointed out that the World Health Organisation and other agencies classified the B1617 strain as a variant of concern only in early May, after the infections in Singapore had occurred.

“I think hindsight is 20/20 here,” he said. “Although the overwhelming outbreak in India – and perhaps more importantly, the displacement of all other variants in India by this variant – would have signalled that greater caution was necessary here.”

Spreading the virus

Phylogenetic test results from an initial batch of infected airport workers found that they had the B1617 variant, and were similar enough that they pointed to a common source of infection.

Early signs suggest that this initial transmission could have occurred through an airport worker who had assisted a family from South Asia, said the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore and Changi Airport Group in a joint statement on Friday (May 21). The family later tested positive for the virus.

It remains unclear exactly how the virus subsequently spread to other workers and members of the public, although doctors have pointed to the air-conditioned environment as a possible contributing factor.

Some infected workers having their meals in the Terminal 3 foodcourt could also have exposed other diners to the virus.

In addition, the airport has segregated the immigration halls, baggage belts and toilets used by incoming passengers from different risk categories, suggesting that these areas may also be suspect.

As the more transmissible Covid-19 variants appear able to spread in such enclosed spaces despite existing infection prevention and control protocols, these measures may need to be enhanced, Prof Howard said.

It is also possible that the current polymerase chain reaction tests may not have picked up some infections caused by virus variants, added infectious diseases expert Paul Tambyah, president of the Asia Pacific Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infection. “That may have contributed to silent transmission by people who may have tested negative, but had actually been infected,” he said.

The discomfort of working long hours in personal protective equipment – including N95 masks, face shields and medical gowns and gloves – may also have increased the likelihood of lapses in infection control measures, said Dr Leong Hoe Nam, another infectious diseases expert from Rophi Clinic.

“I have trouble myself… Wearing full headgear without a break is extremely challenging,” he said. “Hence, implementation and practicality is a big concern.”

All the experts stressed the importance of vaccination in helping to keep cases mild and the cluster under control, with Professor Teo Yik Ying, dean of the Saw Swee Hock School, summing it up as follows: “I believe the outbreak among airport front-line workers would be bigger, if not for the fact that many of these workers have already been vaccinated.”

Plugging the gaps

What can Singapore now do to plug the gaps in its defences that the Changi Airport cluster has revealed?

First, employers should ensure that front-line workers are properly trained and equipped for their tasks. Unvaccinated staff should also be redeployed to less risky environments, especially if they are elderly.

“We would not send partially or untrained soldiers into battle,” Prof Lim said. “The parallel here would be whether our front-line staff – like airline staff, cleaners and immigration officers – are adequately trained and resourced for the pivotal roles they play.”

Importantly, such workers should have access to “good quality standardised occupational health services which encourage them to get tested for all infectious diseases”, Prof Tambyah added. In particular, they should be able to take medical leave without being penalised, he said.

ST PHOTO: KUA CHEE SIONG

Next, those reviewing the cluster should look beyond the individual, scrutinising instead the complex systems involved in stopping viruses from spreading.

As the healthcare sector has learnt, the design and engineering of buildings and work processes are equally important as, if not more than, the individual’s role in preventing infection, Prof Hsu said.

Lastly, Singapore has to remain open to the fact that new gaps will emerge, and be poised to adapt quickly to these challenges.

Dr Arpana Vidyarthi, an academic hospitalist with the University of California in San Francisco, pointed out that blind spots exist and will continually evolve.

“Our systems are complex and adaptive – we fix one hole, and another reveals itself,” said Dr Vidyarthi, an American specialist physician who worked in leadership positions at Duke-NUS Medical School and the National University Hospital for eight years before returning to the United States. “The key is to expect them, keep fixing them, and continually search for new ones.”

Although the new variants are more transmissible, they are not impenetrable, she said, adding that Singapore has one of the most advanced public health infrastructures in the world. “Trust the experts, there are many of them.”

Added Prof Teo: “Despite the best planning and forward planning, there will be new gaps that emerge and we will need to remain agile.”

This is why the country has not eased off on measures such as mask wearing and social distancing, and continues to encourage Singaporeans to work from home to some degree, he said.

“We know that there will be the inevitable spillovers from time to time, and we need to minimise the chance that these spillovers result in an uncontrollable community outbreak.”

Source: Read Full Article