Why Chanel Miller wants you to know her name

What do we know about Emily Doe? We know she was sexually assaulted by Brock Turner outside a frat party at Stanford University, California, one night in January 2015. She was found unconscious and partly-clothed, near a dumpster.

He would get a six-month term, for sexually assaulting an intoxicated victim, sexually assaulting an unconscious victim and attempting to rape her.

He would serve three months and be put on probation for three years, ending this month. Judge Aaron Persky, who was later removed from his post, cited Turner’s good character and the fact he had been drinking.

Much of the coverage at the time also focused on the fact Turner was a star swimmer.

What do we know about Chanel Miller? Maybe you don’t know a lot, yet. If you’ve read the victim impact statement she addressed to Turner, which went viral when she was still known as Emily Doe to protect her anonymity, you’ll know she is brave and articulate.

Here is what you should know about Chanel.

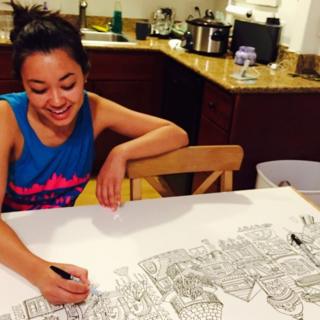

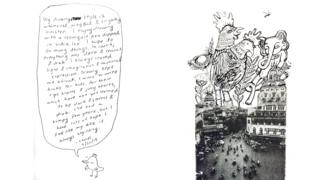

She is a literature graduate, who has now written a book, Know My Name. She is a talented artist and would love to illustrate children’s books, her drawings being a little surreal and – by her own description – sinister. She has also studied ceramics and comic books, and done stand-up comedy.

She loves dogs. She describes herself as shy. She is half-Chinese, her Chinese name being Zhang Xiao Xia (with Xia sounding like “sha”, the first syllable of Chanel). She smiles easily, is thoughtful and funny. She is someone’s daughter, sister, girlfriend. She could be someone you know.

Warning: This story contains content that readers may find distressing

Chanel’s memoir brims with the rage of her ordeal. But why write it, when it meant reliving her pain, reading the court documents and witness statements that had been – until then – kept from her?

She says she felt a duty to shine a light on the darkness so many young women have to go through.

“I’ve had days where it’s extremely difficult to get up in the morning,” says Chanel, 27, speaking in her home city of San Francisco. “I’ve had days where I really could not imagine a single pathway forward. And those were such weighing times.

“And it was terrible. I wouldn’t draw anything, I wouldn’t write anything. All I wanted to do is sleep so that I wouldn’t have to be conscious. That’s no way to live.

“I think of other young women who have to go through this and you see them withdraw and crumble and fall away from the things that they love. And I just think – how, how do we let that happen?”

Her voice is articulate and clear but it vibrates with emotion, and quiet fury, at the injustice of this happening to other women around the world. An endless parade of other people who know what it is to be Emily Doe.

“Here are these young, talented women excited for their futures, who have so many things to give and offer. And something like this happens,” says Chanel. “And they go home, and they carry the shame, and they swallow it up and it eats them from the inside out.

“And they think ‘everything would be better off if I was just holed up in my room’, ‘maybe things would be better if I didn’t speak at all’. ‘Maybe I don’t deserve to be loved or caressed gently’.

“It’s so sick, that we let this happen. That we let them digest these negative ideas of themselves. And let them be isolated. Instead of coaxing them back out here and saying, no, you deserve a full life. You deserve an amazing future.”

Chanel wasn’t a university student at the time – she had already graduated. Her younger sister Tiffany was back home for the weekend and had asked if she wanted to go along to a party with her.

But her story expanded the conversation about campus rape and she wants to see changes at Stanford University specifically, like the fact forensic exams can’t be given at Stanford hospital, with victims having to travel 40 miles.

“Do you get an Uber for 40 minutes with a stranger while you’re still in the clothes you were just attacked in? Do you text your one friend who has a car and disclose that information?”

Many women came forward after reading Chanel’s victim impact statement, emboldened to tell their own stories – in some cases for the first time.

RAINN – the rape, abuse and incest national network, the largest anti-sexual violence organisation in the US – puts the figure at one in six US women being the victim of an attempted, or completed, rape. Every 92 seconds, an American is sexually assaulted. Out of every 1,000 sexual assaults, 995 perpetrators will walk free.

Think of how many women you walk past each day. Think of one in every six.

“We always say like, oh, why didn’t she come forward? Why didn’t she report?” says Chanel.

“Because there’s no system for her to report to. Why should she have faith in us to take care of her if she comes forward? We need to be doing more to help survivors after this happens.”

When Turner was sentenced, the crime was not described as rape – but the law in California has since changed, as a result of Chanel’s case.

There is now a mandatory three year minimum prison sentence for penetrating an unconscious person or an intoxicated person, Chanel’s attorney Alaleh Kianerci explains. Another piece of legislation was written to expand the definition of rape to include any kind of penetration (“The trauma experienced by survivors cannot be measured by what exactly was put inside them without their consent,” she argued, in her support of the bill).

She had felt so beaten down by the court case (“I just felt degraded and empty all the time,” she says) and the shock of Turner’s sentence that when her lawyer asked her permission to release her victim impact statement, she just said “sure, if you think it’d be helpful”. She thought it would end up on a community forum or local newspaper website – never imagining the impact it would have.

When her statement came out, originally published in full on Buzzfeed, it received 11 million views in four days and Chanel was sent hundreds and hundreds of letters and gifts from around the world.

She read them all, saying they “taught me to be gentler to myself, taught me who I was to them”, adding: “I was learning to see myself through them.”

She even got a letter from the White House – Joe Biden, then vice-president, telling her: “You have given them the strength they need to fight. And so, I believe, you will save lives.”

As she was anonymous, it was common for friends to forward the statement to her, unaware she had written it. Chanel’s therapist knew she had been sexually assaulted but did not know her identity as Emily Doe for months, asking her: “Have you read the Stanford victim statement?”

Courts hear from cases like Chanel’s all the time – it’s just the names, the places, the details change. So what made her story, her pain, resonate so widely?

“Maybe not shying away from the darkest parts,” Chanel says. “I think it feels almost like a relief when someone acknowledges your darkness because you feel like it’s this ugly, dirty thing you need to be concealing.

“If you show it, people are going to cringe and back away. I could communicate all of these difficult feelings and be open about them and just lay them out and not feel shame for experiencing them.”

Having been through the court system, Chanel said she felt she had a responsibility to report back, to show others what it is like.

“I know that for me, I had so many, quote unquote, advantages,” she says. “I had my rape kit done [a sexual assault forensic evidence kit]. I had the assistance of policemen and nurses. I had an advocate that was assigned to me, I had a prosecutor, I had all the things you’re supposed to have.

“And I still found it so excruciatingly difficult and emotionally damaging and going through it. I thought, ‘if this is what it looks like, to be well equipped going into this, how the hell is anyone else supposed to survive this process?’.

“I felt that I had a duty to write about what it’s like inside the windowless walls of a courtroom, what the internal landscape is like, what it’s like to sit on that stand and be attacked with this meaningless interrogation.”

Writing the book also allowed her access to the court documents and thousands of pages of transcripts she had not been present for.

While elucidating, it was also deeply painful, knowing what not just the court – but her family and friends had heard and seen.

“It was extremely difficult. I put it off for a really long time. Finally, I thought well, I have to look into them.

“I would read about Brock and the defence talking about, play by play, taking off my underwear, putting his fingers inside…,” she stops, before adding: “It was so graphic and suffocating, to read about myself being verbally undressed again.

“And to imagine it all happening in a courtroom where everyone’s just listening and nobody’s doing anything. I could not stomach it.”

It caused her anger and “self-induced depression” but says there was “this wonderful moment where I’m like, all of these voices in these transcripts are literally in my hands, I can pick them up and put them down. But I own all of them. I get to pick out whichever words I want and assemble them how I want”.

“There is a lot of power in being able to craft the narrative again,” she adds.

Know My Name brims with the trauma Chanel experienced – from waking up not knowing what had happened, to learning details of the assault from news reports, to finally telling her parents, to breaking down in court. As she says, “writing is the way I process the world”.

Chanel only chose to reveal her name six months ago, having started writing the book in 2017.

She says the burden of secrecy had become too much for her – 90% of people who knew her didn’t know her other identity.

Friends thought she was still doing her 9-5 office job. So she had former colleagues (“my suppliers”, she smiles) feed her snippets of information. “In the beginning that was so important for self-preservation and processing and privacy,” she says. “But over time, you feel really diminished. And I think it’s important to be able to live my full truth.”

She expected the day, earlier this month, when she came out as Chanel to be “stormy”. But it was, in the end, a moment of deep calm and strength.

“It turned out to be the most peaceful day I’ve had in the last four-and-a-half years,” says Chanel. “I suddenly realised, I’ve come out on the other side of this.”

She doesn’t feel Turner – who denied all of the charges – has acknowledged what he did.

“You know, at the sentencing, he read 10 sentences of apology,” she says. “It sounded generic to me.

“And it really made me question what we’re doing in the criminal justice system, because if he’s not even learning, then really what is the point? If he had transformed himself, then I think I would have been much more forgiving of the sentence.

“I am really interested in self-growth and understanding that the fact that he deviated so far from that, and was never forced to do any kind of introspection, or to really look at the way he affected me, that really hurt.”

Stanford University responds:

We applaud Chanel Miller’s bravery in telling her story publicly, and we deeply regret that she was sexually assaulted on the Stanford campus. As a university, we are continuing and strengthening our efforts to prevent and respond effectively to sexual violence, with the ultimate goal of eradicating it from our community.

The closest location for a SART [sexual assault response team] exam is at Valley Medical Center in San Jose. We have long agreed on the need for a closer location and have committed to provide space at Stanford Hospital for SART exams. Santa Clara County, which runs the SART program, is working to train sufficient nurses to staff it.

Much of the criticism towards Judge Aaron Persky was about the relatively lenient sentence given to Turner – sparking a national debate about whether white men from wealthy backgrounds were treated more favourably by the US justice system.

“Privilege is not having to reckon with his own actions to examine his effects on someone who is not him,” says Chanel.

“You know, we have young men of colour serving far longer sentences for nonviolent crimes for having marijuana possession. It’s ridiculous.

“I just kept thinking, where does the punishment come in? When are you forced to be held accountable for what you do in life and not just float through, as if anything you do can never hurt anybody, and you will not be affected by it.

“I think what bothers me the most is that there’s never the suggestion that the victim was also busy having a life before this happened.

“We have our own agendas and goals, and don’t appreciate being completely thrown off the rails when this happens. And when people say, why didn’t she report? It’s like, casually asking, why didn’t she stop everything she was doing to attend to something that she never wanted to attend to in the first place?”

Turner attempted to have his convictions overturned last year, but his appeal was rejected. He remains on the sex offenders register. Turner was banned from the university and is now living with his parents in Ohio.

Asked whether she would like Turner and his family to read the book, she says: “If they choose to read it, and really hear it, I will always encourage that. I will always encourage learning and deeper understanding.

“But I’ve also accepted that what they do is out of my control, that I can only focus on my own trajectory and how I wish to keep moving forward. Mainly, I want the book to exist as a companion.

“I think of it as something you can carry with you and you go through difficult things, something you can physically hold or read in bed late at night, when you feel isolated. I always thought like, what would I have needed to hear when I was going through this?”

She holds a space in her heart for the two Swedish students – Peter Jonsson and Carl-Fredrik Arndt – who stopped the assault, having seen what was happening as they cycled past.

Chanel drew a picture of two bikes and slept with it above her bed after the assault, a talisman to remind her there was hope out there.

She’s since met the pair for dinner. “I always like to say ‘be the Swede’. Show up for the vulnerable, do your part, help each other and face the darkest parts alongside survivors.

“I think the response I’ve been getting makes it sound like people are willing to step up now and really fight for what’s right. And that’s extremely encouraging.”

Now the book is out in the world, Chanel plans to decide what to do with the next phase of her life. But she does so with the hope and belief that the good in the world outweighs the bad.

“On the same night I was assaulted, I was also saved,” she muses. “There was a really terrible thing that happened – and also a really wonderful thing. They say you shouldn’t meet your heroes – but in this case you definitely should.”

Asked what she plans to do now, Chanel says: “I want to write books for kids, for their ripe brains and juicy hearts, which have not yet learned to be dark and serious and drab. I’ve had a bumpy few years, but I have lots of hope. I feel like my life is always beginning.”

In the UK, the rape crisis national freephone helpline is 0808 802 9999. In the US, the national sexual assault hotline is 1-800-656-4673. Further information and support for anyone affected by sexual assault can be found through BBC Action Line

Know My Name is published in the US and the UK on 24 September

Source: Read Full Article