What makes a one-term president?

The late George HW Bush was the last US president to lose a re-election campaign. What sets single-term presidents apart?

George Herbert Walker Bush was a war hero, a congressman, an ambassador, the head of the CIA, Ronald Reagan’s number two and, between 1989 and 1993, the most powerful man in the world.

He also enjoyed a more dubious distinction – membership of the small group of sitting presidents who have stood for re-election and lost.

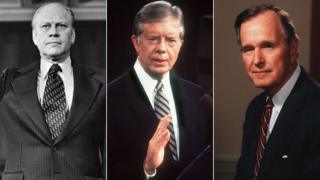

Since 1933, only Bush, Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford have been beaten in a general election while occupying the White House.

Every other incumbent president – including Bush’s son, George Walker Bush, who served from 2000 to 2008 – has been endorsed by the public when they have stood on their party’s ticket.

It is a quirk of no small significance in a nation where eras are defined in the popular imagination by their presidents – from the thwarted promise of John F Kennedy’s early 1960s to the cynicism and paranoia of the Nixon years and the thrusting optimism of Ronald Reagan’s 1980s.

For voters and historians alike, the question of whether the head of state serves just four or the maximum eight years has huge symbolic value.

Donald Trump will be under pressure to run again and retain power come the 2020 election.

In a 2010 ranking of all 44 presidents by 238 eminent scholars for Siena College Research Institute, there were no single-term presidents in the top 10.

The highest-rated incumbent to have been defeated in a re-election campaign was John Adams in 17th place. Kennedy, in 11th place, was assassinated a year before he could return to the polls and James K Polk, in 12th, did not seek a second term.

Why do presidents serve two terms?

Since World War Two, eight sitting US presidents have been re-elected to serve a second term, while only three have failed in a general election.

The presidency offers an unrivalled platform to attract airtime, raise campaign funds and set the policy agenda.

Sitting presidents, too, tend to escape bruising battles for their party’s nomination – although not George HW Bush, who faced a gruelling primary challenge for his place on the Republican ticket from Pat Buchanan.

In addition, they have the rare ability to make a compelling claim – that they know what it is like to take decisions from inside the Oval Office.

“People feel some comfort knowing who is going to be in charge, even if they don’t love that person,” says Julian E Zelizer, professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University.

This carries added contemporary significance after Barack Obama’s two terms.

Obama’s own historical legacy appeared to be as important an election issue as any other, to both the president and his opponents alike, ahead of the 2012 ballot.

Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell famously declared in 2010 that his “number-one priority” was to make Obama, a Democrat, a “one-term president”.

In the same year, Obama himself told Diane Sawyer of ABC News: “I’d rather be a really good one-term president than a mediocre two-term president.”

Defenders of Bush, the 41st president, put him in the former category.

His time in office coincided with the fall of the Berlin Wall and his popularity soared in the wake of the first Gulf War.

However, a protracted economic recession on his watch saw him break a pledge to raise taxes, provoking fierce hostility from within his own Republican party. With Ross Perot, a third-party candidate, splitting the vote in the 1992 election, Bush’s attempts to win re-election were thwarted by the charismatic Bill Clinton.

Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, believes Bush was a victim both of timing and the US’s system of fixed-term presidencies.

“Margaret Thatcher could call an election to capitalise on the Falklands War, but George HW Bush couldn’t do that to capitalise on the first Persian Gulf War,” Sabato says.

“If he could have done that, he would have won.”

George HW Bush: a political life

For Sabato, recent one-term presidents have been the victim more of adverse circumstances than of their own weaknesses.

Carter was unfortunate enough to take office at a time when the global economy was in turmoil while Ford – who assumed office after Nixon’s impeachment – only had two and a half years to make an impact, Sabato insists.

“Events put them in a bad position at the wrong time,” he says.

It’s a perspective that is flatly rejected by Robert W Merry, author of Where They Stand: The American Presidents in the Eyes of Voters and Historians.

In a democracy the customer – that is, the voter – is usually right, Merry argues.

He notes that with only a handful of exceptions – Grover Cleveland, John Quincy Adams – defeated presidents are rarely judged more favourably by historians than by the electorate which rejected them.

“The American people are very unsentimental in their judgments,” he says. “If you look back at one-term presidents, it’s pretty hard to miss the reality that their performance was not quite there.

“Presidents get the blame and they get the credit. I’m uncomfortable with the idea that they are innocent bystanders.”

As a result, he has little time for any suggestion that Bush was under-appreciated by the American public.

“I think he was a fine man, but he was an in-basket president,” Merry says. “He responded to stimuli that came to him. He didn’t have an agenda to change America in any particular way.”

Certainly, Franklin D Roosevelt, Reagan and Obama all inherited economies in dire straits and all won re-election.

What is not in doubt is that, in an average year, an incumbent enjoys significant advantages over a challenger in a US election, thanks to the visibility and prestige of their office.

But that raises the question of what difference a second term actually makes, in practice, to a president’s legacy.

Re-elected presidents are, of course, freed from the requirement to face the voters again, which may offer them some leeway. The very fact they have been endorsed twice at the polls can enhance their authority.

But they face the same institutional barriers and separation of powers as in their first four years – the mid-term elections, the need to win Congress’s support for legislation.

“The president has some more leeway to make decisions in a second term, but they begin to lose their starch,” says Zelizer.

“You find fewer people who are willing to take a job in their administration for a two-year tenure. It’s harder to maintain forward momentum.”

As a result, he says, the defining policies of most presidents tend to occur in their first term.

In Sabato’s view, George HW Bush should not be regarded as a one-term president but as the president who spearheaded a three-term dynasty.

“He had a son who served two terms and served them only eight years after his own,” he says.

“I don’t think there’s any question they viewed it as a personal vindication of the 1992 defeat.”

And given the unpopularity of George W Bush when he left office, it would appear that many people may believe Bush Senior’s one term made him a better president than his two-term son.

Source: Read Full Article