US coronavirus lockdowns drain parents, expose 'digital divide'

Millions of US parents have been working full-time from home while also teaching their children – a daunting task.

Washington, DC – Tina Marie Burgio and her husband have two demanding full-time jobs, two small children and no childcare.

“We are so burnt out, trying to juggle it all,” Burgio, 40, says of her new normal of having to work, teach her children aged four and six, cook meals and keep the house in order – all with no support while sheltering in place amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Her family is not alone.

More:

-

Coronavirus: Trump disagrees with Georgia push to reopen economy

-

Trump signs immigration order curbing some green cards

-

US official says was removed over Trump-touted coronavirus drug

Over the past seven weeks, millions of Americans across the country have either lost their jobs or been required to work from home, all while trying to keep up with their children’s school work, which for many has gone virtual too.

Burgio, who lives in Austin, Texas, says her school district emails packets of up to 80 pages of worksheets and other materials for her older child on Mondays, which has to be turned in by the following Friday – a near-impossible task, she says, given that she or her husband have to supervise the teaching, and keep their younger child occupied, in addition to having to fulfil the demands of their work, which involves conference calls, correspondence and meetings.

“From the time we wake up to the time we go to sleep we rotate in and out of the office where one works and the other takes care of the kids,” Burgio tels Al Jazeera.

With the vast majority of schools across the US closed until the end of the academic year, many teachers have scrambled to shift their classes online. But how this learning has taken shape, in addition to the expectations involved, has differed greatly across the country, with some schools relying on live instruction, using software such as Zoom, while others focused on assignments that are picked up at schools or emailed to parents.

Although most school officials have said that students would not be penalised for not handing in assignments, parents say they feel immense pressure to ensure that their children do not fall behind academically.

That stress is only compounded for families and students who do not have access to a computer, the internet or other tools needed for distance learning.

“It’s a lot of crying. I’m exhausted,” said Ashley Lueck, the primary caregiver of her two children aged two and nine.

“I’ve had to learn how to do the things my third grader is doing in order to help him. He has comprehension issues and [a] short attention span,” she told Al Jazeera.

Eliza Bobek, a clinical assistant professor at the Graduate School of Education at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, says teachers have been thrown into a difficult situation.

“There’s been across the country a really different idea about what virtual learning or distance learning looks like,” says Bobek, who is also a mother of a five and a 10 year old.

“But sending packets home or saying go to this website, that’s not really school, that’s homework,” adding that she too, has had to “tag-team” with her husband throughout the day while juggling work, taking care of the children and doing household chores.

Other parents, like Anissa, say her seven-year-old son has special needs, and she questions whether the online format has been benefitting her child.

“We get through the material, but is he learning? I have no clue,” says Anissa, who only wanted to be referred by her first name.

For families making a household income of $50,000 or less, 72 percent said they were at least somewhat concerned about their child falling behind academically, compared with 56 percent of parents from high-income households, according to a survey by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research in late March.

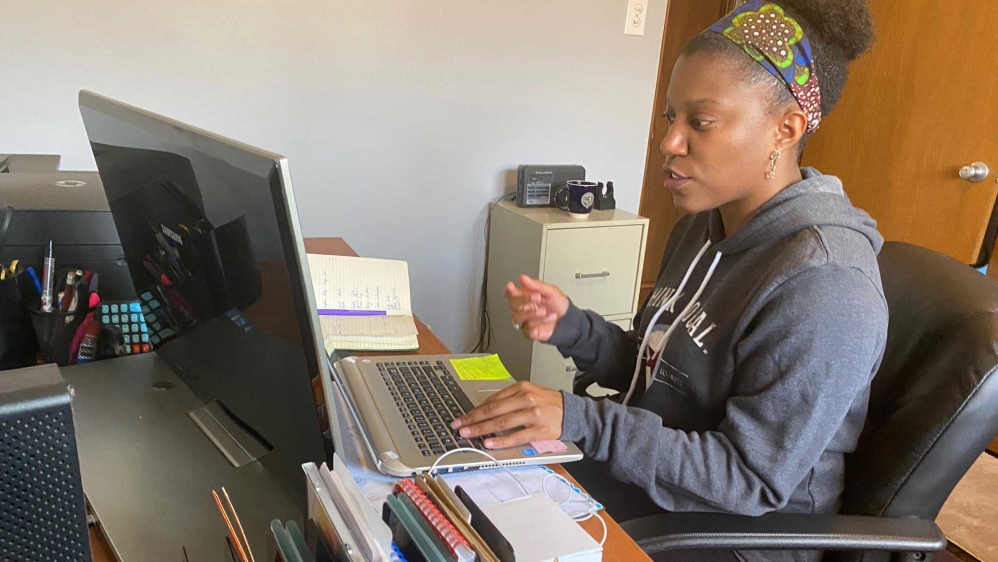

Digital divide

Many students from low-income households also have the added stress of getting access to online material and the tools needed to complete their work.

An estimated seven million school-aged children lived in households without an in-home internet service in 2017, according to the Department of Commerce. The majority of those without home internet services lived in low-income households. Racial disparities also played a role.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center last year found that 82 percent of white Americans reported owning a desktop or laptop computer, compared with 58 percent of African Americans and 57 percent of Hispanics.

Renana Fox, a drama teacher at Plummer Elementary School in Washington, DC, where 88 percent of the students are Black and 12 percent are Latino, says among her older students, half have looked at the material she uploaded on the school system, and only 20 percent have submitted work.

And access to digital assets such as a computer or tablet is a problem, she says.

“We’re doing a fundraiser to raise money to buy tablets for students who don’t have that,” Fox tells Al Jazeera. “But there is so much need that the primary funding is going towards high schoolers and if there’s funding left over it will go towards elementary school.”

Jordan Shapiro, author of The New Childhood: Raising Kids to Thrive in a Connected World, says the abrupt shift in schooling has been more of an emergency learning plan, rather than a distance learning plan, one that has exacerbated existing race and class inequalities in the US, in what he referred to as the “digital divide”.

The expectation that children can learn from home, he says, also assumes that students have access to high-speed internet, computers or tablets, a quiet space to work at home and a parent that is available to supervise or help.

Shapiro adds that despite some recent efforts to bridge this divide, such as schools distributing tablets and computers to students and internet companies offering discounted access, it may not be enough.

“We also have a divide in terms of who is capable of navigating a digital world, who is capable of really feeling a sense of agency in a digital world, who has had practice,” Shapiro told Al Jazeera, explaining that for children who have had their own devices for years, they feel “autonomous” and “free” when online, unlike students who have not had access to technology devices and may feel limited by them.

“It’s an epistemological divide where if you didn’t have a device pre-pandemic and you still don’t have one or just got one, you have not learned how to think in that way, you are at a total disadvantage in terms of not just your access to a Zoom meeting, but your capacity to participate well in that meeting,” he said.

Other parents say amid a barrage of learning apps, video meetings and emailed assignments, they are considering giving up entirely on teaching for the rest of the academic year.

Melissa Whitaker from Havasu City, Arizona, is a mother of five with three children still living at home. She lost her job as a restaurant manager earlier this month and does not have internet at home.

“My kids are doing packets from school and are supposed to attend zoom classes,” Whitaker says.

“[But] I have no electronics to do those on other than my phone when I can get internet.”

Instead, she says, they have been reading, taking walks, doing art projects and playing board games.

“It’s a little rough,” Whitaker adds. “The kids are great, though.”

Source: Read Full Article