Tom and Jerry: 80 years of cat v mouse

A cartoon cat, sick of the annoying mouse living in his home, devises a plot to take him out with a trap loaded with cheese. The mouse, wise to his plan, safely removes the snack and saunters away with a full belly.

You can probably guess what happens next. The story ends as it almost always does: with the cat yelling out in pain as yet another plot backfires against him.

The plot may be familiar, but the story behind it may not be. From Academy Award wins to secret production behind the Cold War’s Iron Curtain – this is how Tom and Jerry, who turn 80 this week, became one of the world’s best known double-acts.

The duo was dreamt up from a place of desperation. MGM’s animation department, where creators Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera worked, had struggled to emulate the success of other studios who had hit characters like Porky Pig and Mickey Mouse.

Out of boredom, the animators, both aged under 30, began thinking up their own ideas. Barbera said he loved the simple concept of a cat and mouse cartoon, with conflict and chase, even though it had been done countless times before.

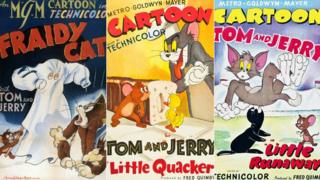

Puss gets the Boot became the first released in 1940. The debut was a hit and won the studio an Oscar for best animated short. Despite their work, the animators were not credited on the win.

Managers initially told them not to put all their eggs in one basket. A change of heart came only when a letter arrived from an influential industry figure in Texas asking when she would see another one of those “wonderful cat and mouse cartoons”.

Jasper and Jinx, as they were first known, became Tom and Jerry.

According to Barbera there was no real discussion about the characters not speaking, but having grown up with silent films starring Charlie Chaplin, the creators knew they could be funny without dialogue. Music composed by Scott Bradley underscored the action and Tom’s trademark human-like scream was voiced by Hanna himself.

For the best part of the next two decades, Hanna and Barbera oversaw the production of more than 100 of these shorts. Each took weeks to make and cost up to $50,000 to produce, so only a handful could be made every year.

These Tom and Jerrys are almost universally considered the best, with rich hand-drawn animation and detailed backdrops helping win them six more Academy Awards and cameos in Hollywood feature films.

“I’ll bet when you watched them as a child, or even if you look at them right now, you would be hard-pressed to know when they were made,” says Jerry Beck, a cartoon historian who has worked in roles across the industry.

“There’s something about animation. It’s evergreen, it doesn’t fade,” he says. “A drawing is a drawing, it’s like when you go see paintings. Yes, we know they’re from the 1800s or 1700s – it doesn’t matter and it still speaks to you today.”

“That’s the thing with these cartoons. What we’ve learned in time is that they really are great art. They’re not disposable throwaway entertainment.”

When producer Fred Quimby retired in the mid-1950s, Hanna and Barbera took over MGM’s cartoon department just as budget cuts closed in. Studio bosses, threatened by the growing popularity of television, realised they could make almost as much money by re-issuing the old shorts as they could by making new ones.

When their department was closed down in 1957, Hanna and Barbera set up their own production company.

But only a few years later, MGM decided to revive Tom and Jerry without its original creators. In 1961 they outsourced to a studio in Prague to save on costs. Chicago-born animator Gene Deitch was tasked with heading the remake, but struggled with a tight budget and staff with no knowledge of the original.

His studio also secretly made episodes of other cartoons, including Popeye. Czech names were Americanised on the credits to stop viewers associating the shows with Communism.

“Because of the Iron Curtain, the animators in the studio here in Prague had never ever even seen a Tom and Jerry cartoon,” Deitch later told Radio.cz.

He knew, being the first to follow up the classics, that he would be “in the line of fire” from fans, and his 13 cartoons are regularly labelled the worst. In interviews Deitch was honest about their bad reputation and revealed he even received a death threat over them.

After him the task fell to Chuck Jones, best known for his work on Looney Tunes at Warner Brothers. Under him, Tom’s eyebrows grew thicker and his face more twisted, and was more like the Dr Seuss character the Grinch that Jones also animated.

Mark Kausler, 72, is one of many people who have warm memories of Tom and Jerry growing up. He dragged his father to see reels of the shorts, over and over, at his local cinema in St Louis. He began making his own cartoons, partly inspired by the characters, and went onto an extensive animation career of his own.

“So much of it is based on the way they look and the timing and the way the music works and everything,” he says. “It was such a wonderful formula, the way everything interconnected.”

“And when they tried to disassemble and reassemble it with another crew and with another type of designer and other comedy – it just rings inauthentic to me, if you know what I mean.”

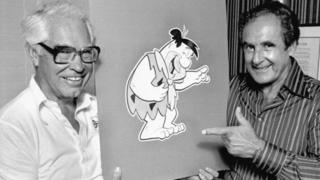

He came a little too late into the industry to work on Tom and Jerry itself, but remembers the excitement of the “monumental” moment Hanna and Barbera showed up to his animation school.

At MGM, television had been seen as a “bad word”, but after going it alone Hanna and Barbera pivoted into the platform. With longer episodes and smaller budgets, they adapted their animation style and used tricks to save time and money.

Their cartoons dominated children’s television for decades. They first found success in the early 1960s with characters like Huckleberry Hound and Yogi Bear and soon, more hits like The Flintstones, Top Cat and Scooby Doo followed.

In the 1970s the pair returned to Tom and Jerry. By then, many of the early episodes were considered “too violent” under fresh guidelines issued to networks. New episodes, with the duo as friends, never lived up to the success of the originals.

Like other cartoons of the time, the show’s legacy has also been complicated by long-standing criticism of its depictions of race. In particular, the character of “Mammy Two Shoes” – a black housemaid with an exaggerated southern accent usually seen from the waist down – has been labelled an offensive racial caricature. Parts of the series also contain jokes using blackface and derogatory depictions of Asians and native Americans.

When the originals were broadcast on US television in the 1960s, some scenes were edited out with “Mammy” replaced with new characters added by Jones’s team. Today the worst-offending episodes are usually cut from re-release collections and streaming platforms. Attention was drawn to this in 2014 when Amazon Prime Instant Video added a “racial prejudice” warning to the series.

Tom and Jerry, with its slapstick violence and dark comedy, remains extremely popular around the world today. It can be found on children’s television everywhere from Japan to Pakistan and a new mobile phone game has more than 100m users in China.

The show has also, surprisingly, found itself in news headlines. In 2016, a top Egyptian official tried to blame the cartoon for rising violence in the Middle East and Iran’s Supreme Leader has compared their US relations to Tom and Jerry at least twice.

As a regular on the BBC schedule for decades, it became particularly well liked in the UK and a 2015 poll named Tom and Jerry as the most popular cartoon in Britain among adults.

In the 80 years since their creation, the cat and mouse have appeared in everything from a “kids” version to a 1992 musical movie where they sang and spoke.

Bill Hanna died in 2001 and Joe Barbera passed away in 2006. A year before his death, Barbera was credited for the last time on a Tom and Jerry short – which was also his first without his former partner.

“We understood each other perfectly, and each of us had deep respect for the other’s work,” he said of their working relationship.

Warner Brothers, who now own the rights to Tom and Jerry, will release a new live-action film just before Christmas this year. Not much is known about the project, except that actors including Chloë Grace Moretz and Ken Jeong have signed on.

For Jerry Beck, Tom and Jerry’s enduring appeal comes in part from the character’s universal relatability.

“I think most people can identify with little Jerry because there’s always an oppressor in our lives,” he says.

“We always have someone, our boss, our landlord, politics – whatever it is. And we’re just trying to live our lives and somebody wants to disturb it.”

All images copyright.

Source: Read Full Article