The white Southerners who fought US segregation

Its racist past still hangs heavy over the White South. But as with anything, it is rarely as simple as everything being bad – one of the reasons photographer Doy Gorton set out to illustrate the White South, his home, in a more nuanced light, writes James Jeffrey.

The black neighbourhood of Greenville in segregated 1960s Mississippi had never seen anything like it. Neither had Mr Gorton when he encountered white people praying alongside their black brethren during an impromptu street-side Pentecostal revival.

When a burly young white man inside the revival tent spontaneously picked up a small black boy sitting with his family and clasped him to his chest amid thronging songs of praise, Mr Gorton captured with his camera the sort of moment that rarely makes it into discussions about the racist White South.

Growing up in Mississippi, Mr Gorton reacted to legalised white supremacy by joining the civil rights movement. But while abhorring the institutional racism that shaped every aspect of Southern life, he retained compassion and patience for the blue-collar whites who had been left behind by the likes of mechanisation and foreign trade since the end of World War II.

He also bridled at mainstream representations of the White South, which he felt didn’t effectively examine the reality and nuances, such as how class divisions informed racism, and who was really to blame.

As a result, he undertook an 18-month drive across the Mississippi Delta, documenting “the most Southern place on earth,” including encounters with more progressive whites, such as those at the revival, and activists fighting for de-segregation and civil rights, often at great risks to themselves.

“It’s astonishing to me that 50 years later, the enormous sacrifices, the enormous bravery and enormous courage of ordinary white people in the Deep South in dealing with race issues is not recognised,” Mr Gorton says. “So many people suffered but they have been passed over by history.”

Mr Gorton recalls how tense the region, and the country, was at the time, with talk of an imminent race war, how everything was going to blow up, with thousands killed. That a huge conflagration was avoided, he puts down, in large part, to local, ordinary whites who helped keep the peace.

Admittedly, whites who more actively pushed for civil rights typically faced economic reprisals, often losing jobs, or physical violence, even paying the ultimate price.

Kansas-native James Reeb, a pastor who participated in the Selma to Montgomery civil rights marches, died in early 1965 of head injuries two days after being severely beaten by white segregationists.

Shortly afterwards, Vilola Liuzzo, an activist who had grown up in Tennessee, was murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Selma (later in the year, Jonathan Daniels, a white seminarian from New Hampshire, died when shielding a black teenager from a fired shotgun in Hayneville, Alabama).

“When it comes to who has been honoured for the civil rights movement, there are very few white people mentioned,” Mr Gorton says.

But the subject matter alone makes any focus on whites problematic, says Ted Ownby, director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, and editor of The Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi. Other factors are probably at play.

“A lot of the white southern activists I’ve come across downplay their significance, saying that they were just the leader of an organisation, or a Christian activist” Mr Ownby says. “And they emphasise they were not as significant as nor sacrificed as much as the African Americans involved who couldn’t go back to a safe place.”

There is also the Atticus Finch factor – the lawyer hero from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, who defends a black man in Alabama accused of rape.

“There’s the danger of presenting a white saviour figure,” says Mr Ownby, adding how Finch, while fictional, is probably the best-known representation of white resistance to racism.

“Of creating hero worship for people whose heroism came through doing their jobs within the system as it existed. After all, the civil rights movement was about changing the system.”

After getting kicked out of the University of Mississippi for organising protests and events against segregation, Mr Gorton joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the “Marine Corps of the civil rights movement,” he says, “going in when no one else did”.

But he says it was discovering the work of American photojournalist Walker Evans, best known for documenting the effects of the Great Depression, who presented people “in a way that was really very respectful, very thoughtful and very straightforward,” that motivated him to try something similar for the people he’d grown up surrounded by.

He acknowledges that offering a different angle on the narrative of the racist White South is contentious, but explains he sees a parallel with the likes of the British Empire which, despite clear flaws, in its entirety was hugely nuanced and included “lots of people who did decent things”.

The negatives and prints from the trip Mr Gorton made across the Mississippi Delta in 1968, along with cassette tape interviews and other materials, moved between trunks and attics for nearly 50 years until Gorton retired to southern Illinois, where he took another look at everything.

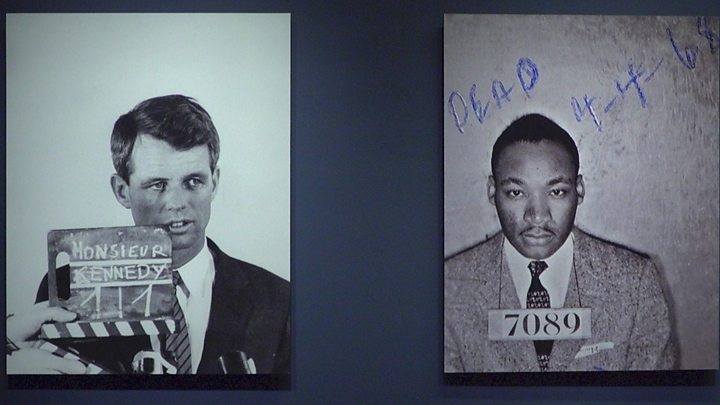

In 2018, the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History in Austin, Texas, acquired his “White South” collection, and it has since been the subject of national and international attention.

More on the Civil Rights movement

David Doggett was long-haired and fresh out of college in Jackson, Mississippi, when he became involved in the underground newspaper movement mushrooming across the US in the 1960s. He says he started Kudzu to address political and racial issues by mixing them up with more appealing material in the paper relating to “sex, drugs and rock and roll”.

“The idea was that people are basically good, even if racist, so I wanted to better inform them,” Mr Doggett says.

“Racism was basically down to misinformation. If you were living in the 1950s in the South, the only blacks most whites came across were field hands and maids, so most people couldn’t conceive that blacks could be intellectually equal to whites. But the civil rights coverage was full of exceptionally smart, educated blacks.”

Participating in protests got him jailed four times – though never for longer than three days, he explains, as he knew “good lawyers” who supported the civil rights movement – as well as physically assaulted.

He says that often it felt he wasn’t achieving much. In 1967 he organised a protest following a police shooting at a nearby black college. It started with two other protesters and finished with 20 white students. Three years later, though, 200 protesters turned out after another incident at the same college.

“It showed how fast things could change,” Mr Doggett says. “Perhaps I can take some credit for being there at the beginning.”

Mr Doggett says that he understands people holding a stereotypical view of the White South as racist, because such a view is “justified.” He agrees with Mr Gorton that the problem of the region’s racism was compounded by the machinations of the White South’s wealthy elite.

“There’s a long history of wealthy whites manipulating poor whites to put the blame on blacks,” Mr Doggett says. “People became so full of racial hatred that they couldn’t see that blacks were actually their allies.”

It’s not possible to say with any degree of accuracy what percentage of the White South was racist, Mr Ownby says. What’s most likely is that the majority were neither on the left, supporting civil rights activists, or on the far right, supporting the language and tactics of massive resistance, he thinks.

Even if not keen on integration, many whites were uncomfortable with some parts of white resistance against it, he says, and didn’t want to be associated with those defending segregation violently.

“While there certainly were white Southerners who advocated for civil rights for black Americans, many more didn’t,” says Ansley Quiros, a historian and author of “God With Us: Lived Theology and the Black Freedom Struggle in Americus, Georgia, 1942-1976.”

“In some ways it’s easier – at least for Americans – to tell those few, heroic stories than to grapple with the majority position.”

Mr Gorton recalls photographing an era when “everything was changing” yet it was unclear what would come next. The Supreme Court had ordered the immediate integration of schools in the South, the Vietnam War raged, and Neil Armstrong walked on the moon. To many it looked like anything could happen, which wasn’t all that reassuring.

“Gorton’s images are as robust and meaningful as texts for understanding the tensions and anxieties of Southerners of all stripes who found themselves in a society being shaken to its knees by cultural, political, and economic revolution,” says Ben Wright, a historian with the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, which houses Gorton’s photographic archive.

Mr Gorton especially remembers photographing in 1970 white college students attending a “Youth Jubilee” at Edwards, Mississippi, to discuss the likes of race and religion. The gathering attracted the attentions of a group of white bikers, festooned with Iron Crosses and swastikas.

“You could literally look between these two groups and see how one group was looking ahead, realising the direction the world was going, and how the other had no idea,” says Mr Gorton, adding how for the latter group white supremacy was “a crutch, a distraction.”

He notes the parallels today in the face of societal upheavals, such as certain jobs being threatened by technological advances, increasing economic inequality, and, he argues, a ruling elite once again manipulating working class whites, with racism coming back into public discourse.

“There has been progress,” Mr Doggett says. “Sometimes now younger people seem hopeless about the situation, but people have no idea about how bad it used to be – the police would dredge the river for a black person who had been lynched and come across other bodies no one knew about.

“We’ve come a long way – yes, there is still forever to go, but it is better.”

Having spent decades living elsewhere around the US, Mr Doggett says he now often thinks about returning to the South, and is encouraged by how Jackson now has a civil rights museum as well as a strong, progressive newspaper.

But, at the same time, he notes how a visitor to the museum – especially a white one – can leave having been given the impression that all whites were bad all the time, which has a “a depressing effect.”

This in turn, he explains, doesn’t encourage white Southerners – or any Americans – to think more expansively about racial tensions that the South, and the country, still wrestles with.

“I do wish there was more info about those whites who have done progressive things in the South,” he says. “And are still doing them.”

Source: Read Full Article