The big US election issue that’s not Trump

Healthcare tops most lists of voters’ concerns in the US mid-term elections, but it gets precious little coverage in the national media. At a clinic in West Virginia, patients and staff explain why they think the system is broken.

Nearly all the streets in Charleston are quiet on this weekday afternoon, despite it being the state capital.

The road to the clinic is lined with old gas stations and older houses in varying states of disrepair.

In a nondescript brick building, 61-year-old Chevone Daly sits on an exam table in a white-walled room.

She first came here in 2010, after an emergency appendectomy became infected. Without her own doctor to see, she was told: Go to the emergency room or go to the free clinic.

Ms Daly tells me “nobody” she knows can afford healthcare anymore.

Most patients at this clinic are like Ms Daly – America’s working poor, who find themselves with nowhere to go and no money to spend when they fall ill.

At West Virginia Health Right, providers and patients echo the same admonition – the system is broken.

And changes introduced by President Barack Obama that were meant to serve as a safety net have left many still slipping through the cracks.

As patients enter the clinic, a glass window plastered with flyers – reminders about wellness classes and prescriptions – greets them.

And in the centre, a note reads: No matter what happens with the Affordable Care Act, we will remain open for business.

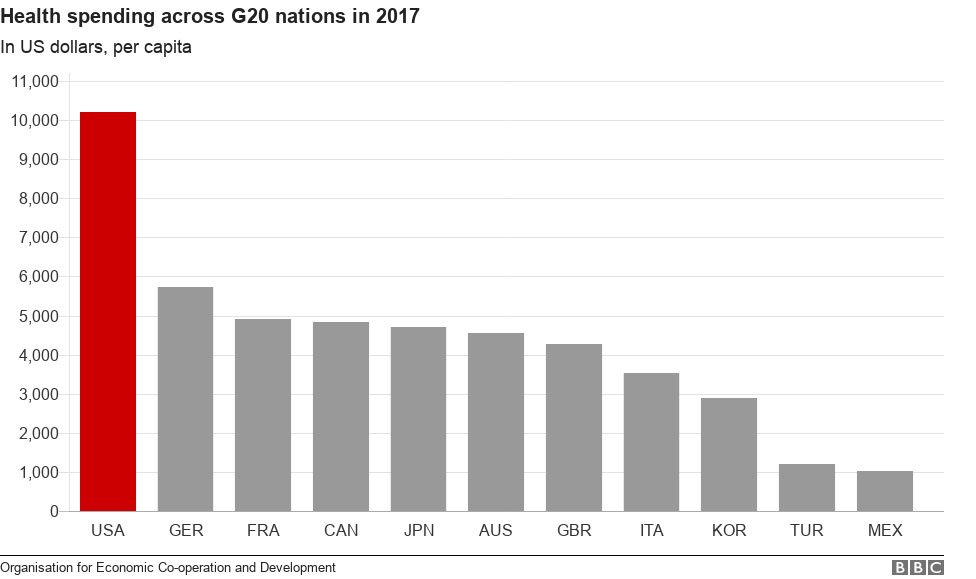

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), better known as Obamacare, was a Democratic answer to America’s ever-increasing healthcare spending – still the highest in the world.

Using state-run marketplaces, President Barack Obama’s signature policy expanded insurance coverage to those unable to access programmes for the poor (Medicaid) and elderly (Medicare).

Its most popular provision by far is the rule that insurers cannot deny coverage over pre-existing conditions like cancer, diabetes and pregnancy. Its least popular consequence has been steadily rising insurance costs.

The latest ACA government report says 2019 premiums are stabilising, more insurers are participating and average premiums have decreased by 1.5% for the first time since 2014. But, premiums for the second-lowest cost plan still increased 37% between 2017 and 2018.

The Trump administration has taken credit for the drop, but some experts say it was due to higher insurance company profits from increasing premiums this year, and that Republican efforts to destabilise the ACA have ultimately made it costlier.

Currently, 11.8m Americans have insurance through the ACA, but around 15.5% are still uninsured – up 2.8% from 2016.

According to a new Pew Research Center study, more than half of Republicans and three-quarters of Democrats say the affordability of healthcare is a “very big” problem.

Founded in 1982, West Virginia Health Right (WVHR) is the state’s largest free clinic, offering no-cost, holistic healthcare for the under-insured and uninsured. With a budget of around $3m (£2.2m) from grants and donations, the clinic provides over $15m of care annually.

As one of the unhealthiest states in the nation, with the highest rate of drug overdoses, obesity and smoking, West Virginia has acutely felt the impacts of national healthcare policies.

WVHR saw 21,000 patients before the ACA. After the law, that number dipped to 15,500, suggesting that fewer patients were in dire need – but that welcome news only lasted so long.

“Now we have 26,211 patients,” says Mrs Angie Settle, 47, nurse practitioner and CEO of WVHR. “We’ve far exceeded where we were.”

And they expect to keep growing as ACA costs rise.

Mrs Settle says the ACA has been “a horrible failure”.

At WVHR, 83% of patients have a job. Many purchased insurance through the marketplace at first, but were forced to drop it.

The nurse practitioner says many of the insurance plans required patients to cover the first $5,000 to $10,000 of their costs.

“It might as well have been $5 million because these people are living paycheck to paycheck. It was totally beyond their reach,” Mrs Settle says.

“You have people making $1500 a month, with rent, childcare and whatever else they have to do. And it’s nothing to have one patient on six to eight medications.”

Mrs Settle also notes that co-pays – the fixed amount insured patients pay – in these plans could be around $50 per service or medication.

She shakes her head.

“When you multiply that, it’s ridiculous.”

The ACA’s high cost has been at the heart of the Republican attack on Democrats for years. Repealing the act was a cornerstone of Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign.

With a Republican-controlled Washington, the last two years have seen a slow but steady dismantling of the ACA: the individual mandate was repealed, enrolment periods shortened, ad budgets slashed, reimbursement payments ended.

The ACA has been hobbling along, but with high premium, prescription and deductible costs, fixing it is a key midterm issue.

But the difference now is that Democrats are embracing it as their number one issue.

According to a recent report by the Wesleyan Media Project, 50% of all Democratic ads in federal-level campaigns tackled healthcare – a stark contrast to Republicans’ 21%.

Last week, President Trump published an opinion piece warning voters that government-run healthcare would bring the country “dangerously closer to socialism”, and in June, his administration backed a lawsuit against the pre-existing conditions clause.

But many Republicans up for re-election have scrubbed harsher critiques of the ACA from their campaign pages.

Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a congresswoman of Washington state, swapped her nearly 300-word statement on repealing the “radical health care bill” for two paragraphs on local policies.

Rhonda Francis, 49, WVHR’s clinical and pharmacy coordinator, joined 19 years ago when she says turning patients away at retail pharmacies when they couldn’t afford their co-pays took its toll.

She described how some newly-insured clinic patients ended up self-regulating medications like insulin to avoid out-of-pocket payments – and ended up in the ER as a result.

“If the patient is going to go without and can’t afford it, what’s the point? They’re just going to jack up hospital costs. Somebody’s going to have to pay for it, eventually.”

“Healthcare should be universal across the line,” she adds. “How are you to know who’s going to be able to pay what?”

In West Virginia, a precarious job climate has seen some residents making six-figures one day and being unemployed and uninsured the next.

“We have patients who’ve worked all their life and they’re really sad when they come in here,” Ms Francis says. “They’re like, ‘I would never have thought I’d be in this situation.'”

Other voices on healthcare

As tensions rise, health policy analyst Paul Keckley believes America is near a tipping point.

“Going into 2020, presidential candidates will have to address specifically their plans to transform the system,” he says.

“It’ll basically boil down to one of two theories – healthcare is a fundamental right, or, healthcare is a marketplace.”

Mr Keckley, who served as a mitigator between industry and lawmakers at the White House during the early stages of the ACA, adds that without a fix, the country will “absolutely” see debilitating cost increases for patients.

Capping spending, like European systems do, will be key, he says.

So will linking social services and healthcare – most comparable nations spend far more on preventive and primary services than the US.

“We call a lot of those ‘welfare programmes’, so they have a stigma, and yet we’re finding out if people live in areas of food insecurity or have unclean air and water or high crime rates, guess what? Their care is going to be more costly and they’re not going to be as healthy.”

But fleshed out solutions from politicians are still few and far-between.

When I ask WVHR patient Ms Daly what could fix healthcare for people like her, she looks down and quietly offers: “Maybe more like what Canada’s is?”

Progressive Democrats have been pushing a system like Canada’s and Britain’s- so-called Medicare for All, as proposed by former Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders.

Funded by higher-taxes, the universal plan would expand America’s pension programme to everyone, taking the burden of paying premiums, co-pays and deductibles out of the equation.

It would cause US spending on healthcare to increase by more than $3tn according to one analysis – but if nothing changes with the present system, the US could spend over $5tn by 2026.

A March Kaiser Health poll found 59% of Americans do favour a Medicare for All plan, including about a third of Republicans polled. One in 10 voters said a candidate’s views on a national health plan will be the most important factor they consider.

But keeping protections for those with pre-existing conditions could become the most important issue for any candidate. Last month, Kaiser polls showed 75% of the public were in favour of the policy.

In West Virginia, Democrat Joe Manchin, up for re-election next month, has emphasised this in his campaign against Republican challenger Patrick Morrisey.

His state will certainly feel the loss of the pre-existing conditions clause if Republicans end it.

Indeed, there is a sense of “panic” among patients and staff at the clinic about losing that provision from the ACA. Many told me about the staggering rates of obesity, diabetes, substance abuse and mental health issues in West Virginia.

As she sits in a dentist’s chair on the second-floor of the clinic, 21-year-old Ricci Shannon, says West Virginians rarely think about their own health in terms of risk.

“It’s such a financial issue for people and they live not-healthy lifestyles,” she says. “No one my age even thinks about it.”

“I’m a person who fell through the cracks,” says Margaret Grassie, 57, by way of introduction. “And this clinic saved my life.”

“I woke up and my prescriptions were $1200 a month,” she says. “With the medications I take and the pre-existing conditions I have, there was no way. I couldn’t afford it.”

Despite working full-time, Ms Grassie could only afford catastrophic coverage from the ACA marketplace. That meant her policy applied just in drastic cases – “I literally had to get hit by a bus,” she explains.

“Donald Trump doesn’t give a crap about me. Hillary Clinton didn’t give a crap about me,” Ms Grassie adds.

“We get written off.”

She tells me West Virginians are scared of healthcare. She tells me of a friend, employed for 33 years, who cannot afford to see a doctor for even preventative care.

“[If] she quits her job, drops her income and ends up here, she gets the help she needs,” Ms Grassie says, gesturing at the free clinic behind her.

“[People] are doing their jobs, showing up everyday for 33 years – and walk out with no insurance.”

As the midterms approach, poll numbers show addressing the cracks and crevices of this health system remains the number one issue for voters, regardless of party.

“It’s gonna take a miracle,” Ms Grassie says with a laugh. “But I think the ACA is a good place to start – fixing it.”

Photographs by Hannah Long-Higgins

.

Source: Read Full Article