The awkward questions about slavery from US tourists

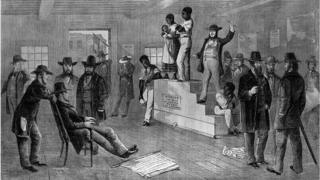

It was late in the summer of 1619 that a ship bearing “not any thing but 20 and odd Negroes” docked at the fledgling port of Point Comfort, Virginia.

Those Africans were the first victims of the American slave trade, 400 years ago.

It has been 154 years since Congress abolished slavery. Since that time, only five generations of African Americans have been born free.

Forty percent of all the slaves that were brought to America came through Charleston, South Carolina. The homes they were sold into, where they were forced to work until death, are now tourist attractions branded on picturesque allure.

But Charleston reflects a wholly American truth: that nothing here is untouched by the legacy of slavery, even centuries on. What is less certain is how a city – and a nation – should talk about such a difficult past.

“Slavery was not that bad – it’s probably the number one thing we hear,” says plantation tour guide Olivia Williams.

“To my face, people have said: Well, they had a place to sleep. They had meals, they had vegetables.”

Williams, 26, is among the guides criticised in reviews of McLeod Plantation that recently caused a stir online. Many were stunned that white visitors to plantations would push back against hearing the slave side of the story.

While McLeod has far more positive reviews than negative ones, the discord struck at the heart of a debate unfolding across historic sites in cities like Charleston.

For decades, tourists have been drawn to Charleston and its plantations for the idyllic southern charm, a deliberate throwback to a Gone With the Wind era.

But the industry is slowly changing as some believe tourists should face the truths of slavery instead of the rose-coloured narrative peddled for so long – even if it makes them uneasy.

Entering McLeod through its small visitor’s centre, there are already signs that this will be a different kind of tour. A board at the front asks: Do you think plantation owners like the McLeod family experienced these tumultuous times differently than the Dawsons, the Forrests, and other African American families who lived here?

Our tour begins on the driveway, which sets exactly the kind of scene you would expect on a plantation visit.

Grey gravel encircles a pristine, sprawling lawn, lined with old trees dripping with Spanish moss that dapples the sunlight. At the heart of the property sits an elegant white home, the very picture of southern splendour.

This image may be what draws many of McLeod’s visitors, but it is not what these interpreters of history want you to focus on.

On her tour, Williams does not directly address the controversial, if atypical, reviews. But she does offer a warning with her welcome.

“We do things a little bit differently than they do at other plantations in Charleston, because we do focus our perspective on the enslaved people,” she tells our group.

“What we’re going to talk about today is hard,” she continues. “You may feel uncomfortable. You may feel upset, sad or angry, and that is perfectly fine. If you’d like to walk away, I won’t get offended.”

No one walks away on our tour, but there is shock. There is discomfort.

Many say they never knew that plantation owners forced marriages between “strong” slaves to add to their “stock”; never heard that pregnant enslaved women were whipped lying down (to protect that investment); never learned that a lifetime of labour began as early as age four.

“It’s gut-wrenching,” says Michaela, a young woman from New York. “It sounds like a puppy mill and yet a million times worse. The idea alone of ignoring the horrific part of the story, it makes me sick.”

“I cried,” she adds. “And I’m happy that I’m sad now because it needs to happen that way … you’re responsible to know what happened.”

It is also clear that some, hearing this history for the first time, are struggling to reconcile the beauty around them with the brutality of slavery.

“I don’t know why [McLeod] wanted to more portray [slavery],” a woman from North Carolina tells me, looking down the tree-lined path where three slave dwellings still stand. “I know they worked here, but the owners worked, had to manage this place too. I mean, it took a lot of work to manage one of these plantations, even though it was done with slave labour.”

She muses that it was terrible to enslave people, but “they could’ve never managed all this without slave labour”.

Turning to look at the main house, which at McLeod remains unfurnished and open for self-guided tours only, she adds: “I’d love to see it back in the day … And don’t you just love these old trees?”

At the end of our tour at McLeod, guide Olivia Williams answers a question from a white woman about whether there was a connection between the way plantation owners forced enslaved women to “breed” and “how black women [now] end up having a lot of fathers for their children”.

Williams says these kinds of questions and comments are typical. She has been screamed at, called a racist, a liar, unfit to do her job. A tourist once wrote to her boss, asking for her to be fired. There are days she has left work in tears, wondering whether or not she should return.

But most of the reaction to McLeod has been positive since Charleston County Parks opened the site in 2015. The reviews that prompted so much media attention – and the uncomfortable comments made by some visitors – are a small sliver of the hundreds of others that thanked McLeod’s staff for opening their eyes to truths that can be hard to find, and digest, for white Americans.

This dissonance is in part attributable to a flaw in the nation’s education system: there is a slightly different version of American history taught at each American school.

Growing up in the South, students may never hear the stories of slaves – even when their own city was built on slave labour, says College of Charleston historian Shannon Eaves.

That very fact, she says, is “a fundamental problem” that shines a light on the legacy of racism in the US.

“Slavery very much had an afterlife that has carried us to the present,” says Eaves.

She explains that the echoes of slavery were present in the Jim Crow laws that legalised segregation, codified black Americans as less-than whites, and suppressed their right to vote. These laws were in place from the end of the civil war until the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s.

“That helps to explain perhaps why we’re in 2019 and I can still have students tell me, I’ve never heard this history before,” says Eaves. “And my response is, well that wasn’t by accident.”

Centuries of slavery followed by decades of institutional repression, according to Eaves, has reinforced old narratives that portray black Americans “as second class citizens”. An ignorance of the complete story is behind the persistence of nostalgia for the antebellum south – and for some, a rejection of anything that questions it.

“They wouldn’t go to Auschwitz or Dachau and expect to hear a happy narrative and walk away cheerful, because they have an understanding that this was a place of death and exploitation and forced labor. A slave plantation was just that, even though, yes, this was someone’s home.”

Middleton Place brands itself as home to America’s “oldest landscaped gardens”.

It’s also one of the city’s oldest plantations. There are certainly elements of slave history throughout the grounds, and Middleton offers a slave-focused tour – but if visitors aren’t looking for it, they could miss it.

A sign at the entrance tells guests the gardens and buildings are “the evidence of the work of generations of Africans and African Americans”. The word “enslaved” appears once, and there is no mention of what these people endured as they “maintained the Gardens, worked in the House, husbanded livestock”.

Director of Preservation and Interpretation Jeff Neale says: “If you talk just about the brutality – which you should, alright – but if that’s all you talk about and you leave out the perseverance, the strength of these people, I think slavery becomes a very hollow vessel.”

Neale adds that a lot has changed in the last 25 years at Middleton and that they are working on ways to make the experiences of slaves more obvious throughout the property.

“More people are looking at this and realising that there’s more than just a story of the owners or more than just a story of the grounds.”

He shares that a visitor once told him after a tour that she “learned that slaves had children”.

“As soon as she said it, she turned beet red,” Neale says. “And she goes, well, I knew that, but I never thought of them as being mothers and fathers.”

But while individual tour guides may offer more details about the brutality and suffering that took place on these pristine grounds, Middleton remains largely focused on the plantation as a home, albeit not just for the masters.

Near the end of our tour, slavery becomes the focal point at Eliza’s house – a freed couple’s cottage built in 1870. Most striking is a large board that takes up the entire centre wall of the cottage detailing the names, ages and prices of Middleton’s 2,800 slaves.

There is also detailed information about the US slave trade and some facts about the people who lived in the cottage, but the exhibit has not been updated in 17 years.

Plantations like Middleton, with still-working farms and manicured gardens, are a unique place of history, where it’s remarkably easy to slip into romanticism in ways other historical sites never would.

Weddings, for example, are ubiquitous here. Our walk through Middleton had to avoid a section of the garden where one was setting up. Charleston’s largest plantation, Magnolia, sees several a day. Even McLeod hosts its share of weddings and photoshoots.

“This is a place of labour and great suffering, but this was also a place of family,” Neale says. “Not only for the Middletons but for the enslaved. I think as long as we respect the history, we can also use it as a place for someone to create their own memory out here.”

Not everyone shares that mindset. Last week, a post on Reddit asking if it was reasonable to skip a best friend’s wedding because it was held on a plantation received over 1,000 comments on both sides of the debate.

Kameelah Martin, Director of African American Studies at the College of Charleston echoes Eaves when she says: “We would never go to, say, the 9/11 Memorial and host a big party or have a wedding.”

She says attempting to do so is “really a slap in the face to people of colour in this country”.

“There is no part of American history or American economic history that isn’t touched by slave labour,” Martin says.

“There certainly is a time and place for nostalgia,” she adds.

“[But] mint juleps and relaxing on the veranda didn’t happen because those white slave owners were hardworking people. They existed in a life of luxury because of the enslavement of other human beings, and so we have to talk about those things together.”

Congress banned the importation of slaves in 1808, but an initial population of close to 400,000 enslaved Africans funnelled into the nation grew to nearly four million by 1860.

It was their labour that supplied Britain with cotton during the industrial revolution. Though the slave trade had been banned in Britain and most of Europe by 1807, investors there were “bankrolling slavery” by slave mortgages repackaged as bonds, sociologist Matthew Desmond wrote for the New York Times Magazine.

South Carolina’s total population in 1860 was just over 700,000 – and of that, 57% were slaves owned by some 26,000 white Americans, the highest percent in the country at the time according to census data.

From 1787 to 1808, whites in South Carolina’s Lowcountry bought 100,000 Africans, according to the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

But it was only last year that the mayor of Charleston publically apologised for the institution of slavery – and the city council passed a similar apology by a slim 7-5 margin. So it’s no surprise that it’s still possible to avoid a complete history in favour of a prettier picture of the antebellum South throughout Charleston.

Charleston is a city inextricably entwined with the plantations that gave it global prominence. There are statues of confederate leaders, but there is no official slave memorial. There are countless streets of beautiful, colourful homes with quintessential southern porches in housing developments named after slave plantations.

“Have they ever stopped profiting off of the history of enslavement, I guess that’s the better question,” Martin says. “It went from agriculture to a tourist industry.”

Two of Charleston’s major historic foundations are currently run by all-white boards. The museums director of one preserved manor in downtown told me even as early as the 1980s, docents were barred from using “the s-word” with tourists, but there has been a recent shift to study and promote the stories of the enslaved who lived at these sites.

To Martin, Charleston has a unique “responsibility” as a city so entrenched in history: there is a vast amount of preserved records about its entire population, white and black, exceptional even among other southern states.

Charleston must “[lead] the way in racial healing and reconciliation because it has maintained all of this, this history on both sides of the spectrum,” Martin says.

In 2015, the city of Charleston as a whole was forced to confront its racist past in the wake of a terror attack that saw white supremacist Dylann Roof open fire on black worshippers at the Mother Emanuel church, killing nine. Two months before he opened fire on those worshippers, Roof took a tour of McLeod Plantation. It was one of many stops he made to historic sites in the South.

At the height of slavery, the National Humanities Center estimates that there were over 46,000 plantations stretching across the southern states. Now, for the hundreds whose gates remain open to tourists, lies a choice.

Every plantation has its own story to tell, and it’s own way to tell it. Not all think bringing slavery to the forefront is necessary. But it’s clear that the gilded image of the antebellum south is slowly changing as historians and conservation groups begin to fix decades-old narratives.

When asked why, 400 years on, we should still talk about slavery, Martin says: “Maybe your ancestors didn’t participate, maybe you have no connection to it directly. [But] in 2019 we are still dealing with the implications and the impact and the racial disparities that are a result of that way of thinking, of that way of life.

“If nothing else, you should care because you are a human.”

More voices on race relations in America

.

Source: Read Full Article