Migrant families separation: The big picture explained

President Donald Trump has signed an executive order seeking to end the separation of migrant children from their parents at the US border. How did we get to this point and what is the bigger picture?

The policy – which the administration initially defended as necessary to deter illegal immigration – sparked outrage in the US and internationally.

At the heart of it was the Trump administration’s decision to prosecute all adults who try to cross the US-Mexico border illegally, many of whom plan to seek asylum in the US.

Because migrant children could not be put in custody with their parents, they were separated. As a result, more than 2,300 children were removed at the border between 5 May and 9 June.

Here are three key issues that help give a fuller picture of why this has been happening, and why now.

People are fleeing to the US: why?

There are very few detailed statistics on the reasons people migrate to the US but one Pew Research study from 2011 asked people of Hispanic origin what their main reason for moving was: 55% said it was to seek economic opportunities while 24% said it was to be with family.

Countries in Central America are among the poorest in the world while the US is one of the richest, with the world’s largest economy (by GDP).

According to the World Bank, more than 60% of people in Honduras live below the poverty line, with one in five people living in extreme poverty, or on about $1.90 (£1.45) a day.

Poverty rates are declining in two other countries that are major sources of migrants to the US – Mexico and El Salvador – but they both remain at about 40%.

President Trump has repeatedly condemned economic migrants, saying two months after he launched his candidacy that “they’re taking our manufacturing jobs, they’re taking our money.” Many studies say that immigration produces net gains for the US economy.

There is evidence of one other growing factor for migration: violence.

“We leave our countries under threat. We leave behind our home, our relatives, our friends.”

Maritza Flores, from El Salvador, was one of about 1,200 people who travelled in a so-called “caravan” of migrants north through Mexico in April, headed for the US border.

“Many people think we left because we are criminals,” Ms Flores told the BBC at the time. “We’re not criminals – we’re people living in fear in our countries. All we want is a place where our children can run free – where they’re not afraid to go out to the shops.”

Gang violence is rife in El Salvador and Honduras. According to UN figures, the two nations have the two highest homicide rates in the world.

Rights groups cite the influence of armed gangs who act with impunity – as well as the targeting of women and LGBTI people – as key factors for the high homicide rates.

Among the most prevalent groups is MS-13, a brutal street gang that started in the US but is now thought to have at least 60,000 members in Central America.

The gang is said to recruit at-risk and poor teenagers and demand they commit murder as an initiation rite, often using a machete. In El Salvador, MS-13 controls entire neighbourhoods.

Over the past few years, there has been a significant increase in the number of people travelling to the US because they fear persecution by gangs like MS-13.

People seeking asylum in the US can request a “credible fear” interview if returning home would put their life at risk. An asylum officer then tries to establish if their request is based on a fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political beliefs or membership of a particular group, including a gang.

In the 2012 fiscal year, there were 13,880 credible fear applications. Five years later, according to US Citizenship and Immigration Services, there were 78,564 applications, and the vast majority were deemed to be justified in both years.

In 2017, the highest number of credible fear applications came from citizens of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, three countries with high rates of gang violence.

Mr Trump’s Attorney-General Jeff Sessions has said the credible fear system has been exploited. The fact applicants who passed an initial interview were released pending a full interview “created even more incentives for illegal aliens to come here and claim a fear of return”, Mr Sessions said. Mr Trump has been keen to raise the threshold for what counts as “credible fear”.

In May, the UN’s refugee body said 294,000 refugees from north and central America were registered worldwide during 2017, an increase of 58% on the previous year.

“We hear repeatedly from people requesting refugee protection, including from a growing number of children, that they are fleeing forced recruitment into armed criminal gangs and death threats,” a UN statement said.

As the number of people requesting credible fear interviews has increased, so too has the number of people being detained at the US border.

In April, 50,924 people were held or denied entry while trying to cross the border, compared with 15,776 in the same month last year.

The numbers had dropped significantly in the months after Mr Trump’s election, but have since picked up, which is normal in spring.

In April, the Department of Homeland Security said the initial drop and subsequent rise was because migrants, smugglers and traffickers had initially “paused to see what our border enforcement efforts would look like and if we could follow through on the deportation and removal” before they spotted loopholes.

The recent rise in detention numbers is believed to have played a major part in the zero tolerance policy causing such controversy today.

Five more things to read

The key players and their motivation

To understand the zero-tolerance policy, it helps to understand who is behind it.

When Donald Trump announced his candidacy for the White House on 16 June 2015, he set the tone for how he would later approach the presidency.

“When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

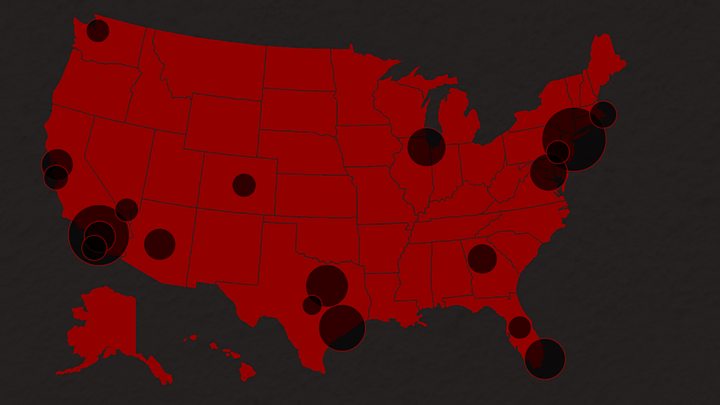

Mr Trump often cites the dangers of MS-13, which sprung up among Salvadorean immigrants in 1980s Los Angeles and has since spread to at least 46 states. Mr Trump has called them “animals” and threatened to rid the US of their influence.

He has focused closely on immigration since becoming president, repeating many of the same claims he made on that day. He has backed proposals to cut the number of legal immigrants to the US by 50% over the next 10 years.

By cracking down on immigration, he is playing to his base, his core supporters. A Reuters/Ipsos poll in April found that 85% of Trump voters backed his hardline stance on immigration. A poll by Quinnipac University on 18 June found that 55% of Republicans backed the family separation policy.

The other key player is Jeff Sessions, the attorney-general who has been repeatedly under fire by the president over the past year, to the extent of being labelled “beleaguered” by Mr Trump in a tweet (this all stems from Mr Sessions’s decision to recuse himself from the investigation into possible links between Mr Trump’s campaign and Russia).

The attorney-general is the man who announced his justice department would now enforce the “zero tolerance” policy, and has been one its most vocal supporters.

He said the “short-term separation of families” was “not unusual or unjustified”. Mr Sessions also cited Bible scripture to support the policy.

Another public defender of the policy is Kirstjen Nielsen, the secretary of homeland security.

She was reportedly close to resigning in May after being subjected to what the New York Times called “a lengthy tirade” by the president over the failure to stop illegal immigrants crossing from Mexico.

A month later, she stood before the press to defend the zero-tolerance policy, saying it was “not a controversial idea” and that suggestions that families were being purposely broken apart to act as a warning to immigrants were “offensive”.

The decision to push ahead with the policy also reveals the growing influence of one man in particular: Mr Trump’s senior policy adviser, Stephen Miller, an immigration hardliner tasked with putting the president’s words into actions.

Mr Miller, one of the president’s few original aides to keep their job, was the person who put together the ban on immigrants from majority-Muslim countries announced soon after Mr Trump came to office.

The New York Times reported that in April, when it became clear that the number of people being held at the border was growing significantly, Mr Miller pushed for a harder line on immigration.

“It was a simple decision,” the 32-year-old told the New York Times. “The message is that no-one is exempt from immigration law.”

The shadow of the wall

Looming large over the zero-tolerance policy is Mr Trump’s desire for a border wall with Mexico. Last year, he said he wanted a wall along half the 2,000-mile (3,220km) border, with natural obstacles taking care of the rest.

He made the wall a key pledge of his presidential campaign, but any immigration bill to fund it requires approval from Congress. And any such bill – drafts of which are now doing the rounds – would need the support of at least nine Democrats in the Senate for it to pass.

At times, Mr Trump’s team have appeared to present a choice to Democrats: it’s enforced separation or the wall. Mr Trump made the link in a tweet on 15 June.

And Mr Sessions repeated the point in a speech in Louisiana three days later.

“We do not want to separate parents from their children, you can be sure of that,” he said. “If we build a wall, if we pass some legislation, if we close some loopholes, we won’t face these terrible choices.”

The policy has drawn comparisons with an ultimatum President Trump made in February, when he tied funding for the wall to the fate of the children of undocumented immigrants. In that case, a court ruling meant that a compromise was not needed.

Pressure was growing from within Mr Trump’s own party to find a resolution to the crisis he created – and he acted.

But there is no indication a plan exists for how to reunite families.

Source: Read Full Article