Chicago cops acquitted of cover-up charge in black teen's killing

Relatives of Laquan McDonald, killed in 2014, call ruling step backwards for black community’s fight for justice.

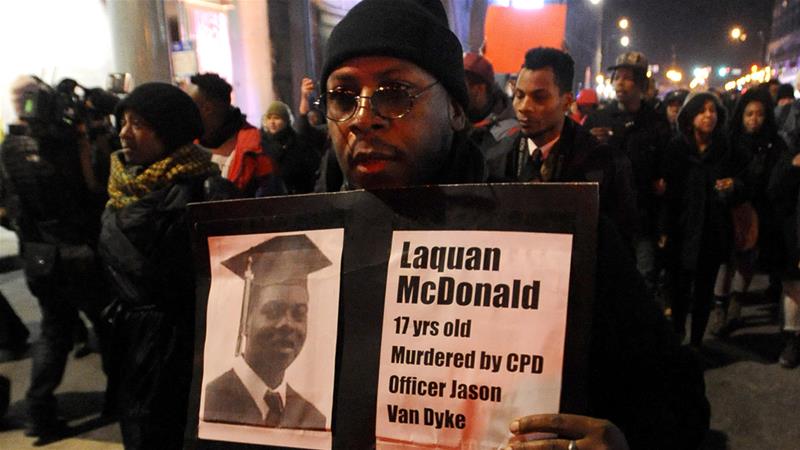

Activists and relatives of Laquan McDonald, a black teenager in the United States who was killed by a white police officer more than four years ago, have decried a court ruling that acquitted three current and former Chicago officers of conspiring to protect a white colleague by lying about the circumstances around the fatal shooting.

The October 2014 killing of 17-year-old McDonald, which was captured on police video, triggered months of protests and became emblematic of long-standing police abuse in Chicago, the country’s third-largest city.

On Thursday, Judge Domenica Stephenson acquitted officers Joseph Walsh and Thomas Gaffney and detective David March of trying to cover up the shooting, dismissing as just one perspective the shocking dashcam video of McDonald’s killing that also led to a federal investigation of the police department and the rare murder conviction of an officer.

In casting off the prosecution’s entire case, the judge seemed to accept many of the same defence arguments that were rejected in October by jurors who convicted officer Jason Van Dyke of second-degree murder and aggravated battery.

He is scheduled to be sentenced on Friday, facing up to 20 years in prison for the second-degree murder conviction and up to 30 years for each of the 16 counts of aggravated battery, one for each shot he fired at McDonald, who was carrying a knife.

The judge said the video showed only one viewpoint of the confrontation and that there was no indication the officers tried to hide evidence.

“The evidence shows just the opposite,” she said. She singled out how they preserved the graphic video at the heart of the case.

‘Sad day for America’

McDonald’s family questioned how the two cases could produce such different decisions.

His great uncle, the Reverend Marvin Hunter, told reporters that the verdict means “that if you are a police officer you can lie, cheat and steal”, adding that it proved the city’s legal system was “corrupt”.

“This is not justice,” he said. “To say that these men are not guilty is to say that Jason Van Dyke is not guilty,” Hunter added, describing the verdict was a step backwards for the black community’s struggles for justice.

“It is a sad day for America.”

Karen Sheley, of the ACLU of Illinois, said in a statement: “The court’s decision does nothing to exonerate a police department so rotten that a teenager can be murdered – on video – by one of its officers.”

The case has provoked periodic street protests since 2015, when the video came to light, and the acquittals could renew that movement.

Eric Russell, executive director of Tree of Life Justice League, a police accountability advocacy group from Chicago’s West Side, said he and other leaders expected hundreds to protest against the verdict on Friday before Van Dyke’s sentencing.

“We will be down here tomorrow by the hundreds, and we will cry out for justice for Laquan,” Russell said.

Special prosecutor Patricia Brown Holmes said she hoped the verdict would not make officers reluctant to come forward when they see misconduct. Her key witness, officer Dora Fontaine, described how she had become a pariah in the department and was called a “rat” by fellow officers.

The trial was watched closely by law enforcement and critics of the department, which has long had a reputation for condoning police brutality.

Walsh, Gaffney and March were accused of conspiracy, official misconduct and obstruction of justice. All but Gaffney have since left the department. They asked the judge, rather than a jury, to hear the evidence.

After the verdict, Walsh would say only that the ordeal of being charged and tried was “heart-breaking for my family, a year and a half”.

In her ruling, the judge rejected prosecution arguments that the video demonstrated officers were lying when they described McDonald as moving and posing a threat even after he was shot.

“An officer could have reasonably believed an attack was imminent,” she said. “It was borne out in the video that McDonald continued to move after he fell to the ground” and refused to relinquish a knife.

The video appeared to show the teen collapsing in a heap after the first few shots and moving in large part because bullets kept striking his body for 10 more seconds.

The judge said it’s not unusual for two witnesses to describe events in starkly different ways. “It does not necessarily mean that one is lying,” she said.

The judge also noted several times that the vantage points of various officers who witnessed the shooting were “completely different”. That could explain why their accounts did not sync with what millions of people saw in the video.

Both Van Dyke’s trial and that of the three other officers hinged on the video, which showed the former opening fire within seconds of getting out of his police vehicle and continuing to shoot the teenager while he was lying on the street. Police were responding to a report of a male who was breaking into trucks and stealing radios on the city’s South Side.

Prosecutors alleged that Gaffney, March and Walsh, who were Van Dyke’s partners, submitted false reports about what happened to try to prevent or shape any criminal investigation of the shooting. Among other things, they said the officers falsely claimed that Van Dyke shot McDonald after the latter aggressively swung the knife at the officers and that he kept shooting the teen because McDonald was trying to get up still armed with the knife.

McDonald had used the knife to puncture a tyre on Gaffney’s police vehicle, but the video shows that he did not swing it at the officers before Van Dyke shot him and that he appeared to be incapacitated after falling to the ground.

Attorneys for Gaffney, Walsh and March used the same strategy that the defence used at Van Dyke’s trial by placing all the blame on McDonald.

It was McDonald’s refusal to drop his knife and other threatening actions that “caused these officers to see what they saw”, March’s lawyer, James McKay, told the court. “This is a case about law and order (and) about Laquan McDonald not following any laws that night.”

City Hall released the video to the public in November 2015 – 13 months after the shooting – and acted only because a judge ordered it to do so. The charges against Van Dyke were not announced until the day of the video’s release.

The case cost the police superintendent his job and was widely seen as the reason the county’s top prosecutor was voted out of office a few months later. It was also thought to be a major factor in Mayor Rahm Emmanuel’s decision not to seek a third term.

The accusations triggered a federal investigation, resulting in a blistering report that found Chicago officers routinely used excessive force and violated the rights of residents, particularly minorities. The city implemented a new policy that requires the video of fatal police shootings to be released within 60 days, accelerated a programme to equip all officers with body cameras and adopted other reforms to change the way police shootings are investigated.

According to the Washington Post’s Fatal Force database, at least 995 people have been killed by the police in the US in 2018. The Post found that more than 980 people were killed by police the previous year.

The Guardian identified more than 1,090 police killings in 2017.

Nearly a quarter of those killed by police in 2016 were African Americans, although the group accounted for roughly 12 percent of the total US population.

According to watchdog group The Sentencing Project, African American men are six times more likely to be arrested than white men.

These disparities, particularly the killing of African Americans by police, has prompted the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, a popular civil rights campaign aimed at ending police violence and dismantling structural racism.

Fault Lines

The Contract: Chicago’s Police Union

Source: Read Full Article