A riot that changed millions of lives

When half a dozen police officers raided a Mafia-run gay bar on a hot New York night 50 years ago, little did they know their actions would spark a movement that reshaped the lives of generations to come.

Mark didn’t throw a brick that night. And he didn’t confront a policeman. But he had something that was perhaps as potent as any projectile – he had chalk.

It was handed to him with instructions by his friend Marty as chaos unfolded outside the Stonewall Inn, the police being pelted with coins and bottles.

The homeless teenager set off up the street to scribble three words on the pavement. Then he did the same on a brick wall further up the road.

Three words. “Tomorrow night Stonewall”

That simple message written by Mark was an attempt by Marty Robinson to spread the word, to ensure that a spontaneous act of defiance was transformed into something bigger. An hour earlier, the police had raided the bar in Greenwich Village for the second time that week, but this time on a Friday night at 1am when it was packed.

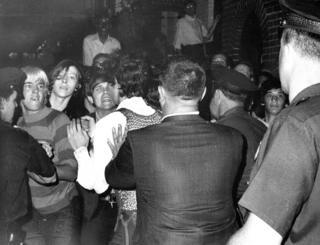

About 200 customers – lesbians, gay men, transgender people, runaway teenagers and drag queens – were thrown out on to Christopher Street. A crowd turned on the officers who retreated inside for their safety. Gay people were used to running from the police, but this time they were the ones on the advance and the men in uniform on the retreat.

The gay rights movement didn’t start that night but it was invigorated by what happened in the hours and days after the first coin was thrown. And all the strides made since, like marriage equality and a more accepting society, owe something to the youths who fought the police and the activists who organised afterwards.

Stonewall has been described as the Rosa Parks moment for gay rights. And just as Ms Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a bus in Alabama to a white man had the effect of animating the civil rights movement 14 years before, so Stonewall electrified the push for gay equality.

In 1960s America, gays and lesbians were effectively outlaws, living in secrecy and fear. They were labelled insane by doctors, immoral by religious leaders, unemployable by the government, predatory by TV broadcasts and criminal by police.

So what was it that made them suddenly fight back on the night of 27 June 1969?

A fury years in the making

At the time of the uprising, consensual sexual relations between men or between women were illegal in every US state except Illinois. Gay people could not work for the federal government or the military, and coming out would deny you a licence in many professions including law and medicine.

The laws in New York state were particularly punitive despite – or perhaps partly in response to – a growing number of gay men and women moving to New York City from across the US. Thousands were arrested each year in the city for ”crimes against nature”, solicitation or lewd behaviour. Some had their names published in newspapers, which meant they lost their jobs. Even what you wore was policed – fewer than three pieces of clothing deemed appropriate to your gender could put you in handcuffs.

There was a huge amount of anger because gay people had no political power to prevent this, says William Eskridge, a professor at Yale Law School. “It was like a keg of dynamite waiting to ignite.”

Young gay men and women didn’t want to write letters to councillors to enact change or sign petitions, he says. Instead, they took their cue from the anti-war movement, from black power and those pushing for women’s liberation. Their strategy was simple. “Go to the streets and make trouble. Attack, attack, attack.”

There was no refuge for them in bars or nightclubs. The local liquor laws in New York City were interpreted in a way that meant serving alcohol to gays and lesbians could close down any licensed premises because that made the venue “disorderly”. Dancing with someone from the same sex could be interpreted as a “lewd” offence.

A crackdown on the city’s gay bars began in the early 1960s. The Mafia stepped in to run many of them, charging more for watered down drinks and paying off the authorities. Despite this exploitation by the Mob, patrons of the Stonewall Inn regarded it as a sanctuary, a rare place for self-expression and affection. Uniquely, it had a dancefloor.

As the raids increased in frequency in the summer of 1969, with a mayoral election looming, the Stonewall became an obvious target. It was run by criminals and it sold alcohol without a licence. There were also rumours the Mafia was blackmailing its wealthy customers. But as the police closed in, they had no idea what they were walking into – the sense of injustice was palpable, not just from the recent raids but a number of vigilante attacks.

On the hottest night of the summer, all this tinderbox needed was a spark.

‘We were fighting back’

About six officers – including those who led the NYPD’s public morals division – walked across Christopher Street and went into the bar, where undercover colleagues were already inside. The lights came up, the music stopped and the police instructed people to show their IDs as they left.

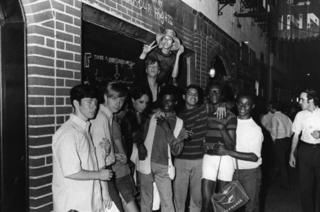

Ejected patrons spilled out on to the street. At first the atmosphere was festive, says Robert Bryan, who was 23 at the time. He arrived on the scene soon after the raid. “There was laughing and joking. People were coming out of the bar striking poses and bowing.”

The mood changed, he says, when a drag queen was attacked by one officer after she hit him with her purse. People started throwing coins at police. It deteriorated further when a lesbian came out of the bar and struggled as police tried to put her in a car. Instead of cents and quarters, the missiles became stones and bottles.

As the police retreated inside, they began grabbing people and beating them, says Bryan, who aimed a kick at one officer before running away with another policeman in vain pursuit. When he returned, the police were trapped inside the building and – they later revealed – fearing for their lives. They were only a handful in number and by now several hundreds of protesters had gathered outside.

A rubbish bin was hurled at the window and lighter fluid used to ignite projectiles. A parking meter was uprooted and used as a battering ram on the front door.

“It was just this emotional, adrenaline-crazed moment, completely irrational,” says Bryan. There was a mob spirit, he says, and he felt like he was in a dreamlike state, acting without restraint. “God knows I would never have kicked a policeman if I were alone. We were finally fighting back and it was exhilarating.”

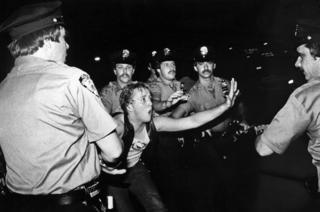

Riot police arrived to rescue their colleagues but the violence went on before it eventually subsided. At least one police officer was treated in hospital for a head wound and 13 demonstrators were arrested.

That battle was over but some of those present knew nothing would be the same again. The following night saw a larger crowd – helped partly, perhaps, by Robinson’s chalk but also a leafleting campaign during the day. It was more violent and police took a more muscular approach, using tear gas. Rubbish cans were set on fire and thrown at them. The protests continued for another four nights, particularly violent on the Wednesday.

But the question on many minds when the uprising ended was – what next?

First steps to freedom

When Martha Shelley, 25, leapt on top of a water fountain alongside Robinson in Washington Square exactly one month after the riot, she feared for her life. But she had an important message to tell the crowd of a few hundred – come out of the shadows and “walk in the sunshine”.

“It was scary,” she says, now aged 75 and looking back to that day. “I was in Harlem when MLK was shot and it went up in flames. I was aware that I could get shot.”

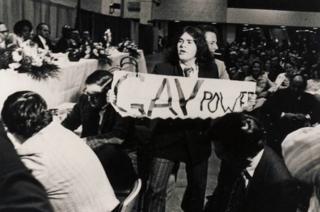

At her urging, and after a stirring speech from Robinson, they all marched to Stonewall Inn, some wearing lavender-coloured sashes, holding hands and chanting “Gay Power!”

This was the first time gay people had openly marched in New York, demanding equality. But it wasn’t the first march for gay rights. There had been an annual one in Philadelphia in front of Independence Hall for a few years, led by the Mattachine Society, the first major gay rights organisation. But that was a courteous affair, says Shelley.

“I went to Philadelphia. Women had to wear dresses. I hated it from the bottom of my heart. We walked around with our signs and the tourists were looking at us like we were something out of the zoo as they ate their ice cream. I thought ‘This isn’t me, it’s fake.'”

Before Stonewall, the activists wanted to fit into society and not rock the boat. But after the uprising, polite requests for change turned into angry demands. The rally organised by Shelley and Robinson does not get the same billing in the history books as the big gay rights march the following year, which has become known as the first Pride march.

But it was hugely significant. The first, courageous step had been taken.

You might also like:

Getting organised

This new mood was best embodied in what became the most important driving force to emerge from Stonewall – the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). It was formed within weeks, and was as much a loose alliance of groups as a single entity.

The name was a nod to the National Liberation Front fighting the US in Vietnam. When it was suggested at a meeting, Ms Shelley was so enthusiastic she banged her hand hard on her beer bottle, drawing blood. “The riots would’ve done nothing if we hadn’t organised afterwards,” she says.

The GLF only lasted a few years but burned brightly in that time, with a gamut of issues to fight.

“Control over your own body was primary,” says Shelley. “That includes sexual liberation, freedom from the draft, women’s reproductive rights, freedom to take drugs without being imprisoned for it, and economic freedom.” And anti-racism, she adds – all those freedoms had to apply to everyone, regardless of race, religion, or citizenship status.

The GLF made alliances with some of the leading insurgent groups of the time, like the Black Panthers. Its members organised the first Pride march and set up a newspaper called Come Out! which Shelley sold on the street.

GLF meetings were chaotic and there were deep disagreements over the best way forward. But its creation marked the start of a new era, leading to a wave of new activist groups like the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) and the radical lesbian group Lavender Menace of which Shelley was a founder member.

A year later there was a GLF in London and the movement became a global one.

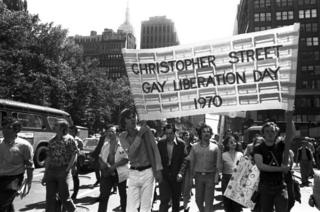

The first Gay Pride march

There are now thousands of Pride events around the world. But it had humble beginnings – it was over dinner with three friends soon after Stonewall that the idea of a more radical march demanding rights came about, says Ellen Broidy.

Christopher Street Liberation Day, exactly one year after Stonewall, began at Greenwich Village and went 51 blocks up Sixth Avenue to Central Park. Reports at the time estimated between 3,000 and 15,000 people took part.

The most exciting thing about it was the number of people who joined along the route, says Broidy. “The core message was ‘We’re here. We’re queer, get used to it.’ But I sensed it was more than that. It was about reaching out and playing our part in the revolution.

“I don’t think any of us were marching for the right to serve in the military or to get married.” It was less about legal change and more about overturning the systems of oppression, she says.

Some people took self-defence classes, so certain were they of violence. But there wasn’t any. Other US cities soon did the same and London had its first two years later.

“It was natural and necessary,” says Broidy. “If it hadn’t happened first in New York in 1970, it would have happened in London or in Madrid or in Mexico City.”

Today, the political message is still there but Pride is more a celebration of gay culture, with music and corporate sponsors.

Broidy thinks something has been lost in the process. “I think it’s much more powerful without the floats and without Citibank and American Airlines. Yes, it’s a sign of progress but in a distinctly capitalist market.”

Making strides

After that first Pride march, the speed of progress went up a notch. In the decade that followed, the federal exclusions on gays and lesbians were lifted, and the medical profession reversed its long-held belief that homosexuals needed psychiatric treatment.

Harvey Milk became the first openly gay elected official in the US, in 1977 in San Francisco. Two years later, about 100,000 people took part in a national march on Washington – probably at that point the biggest gathering of gay people in history.

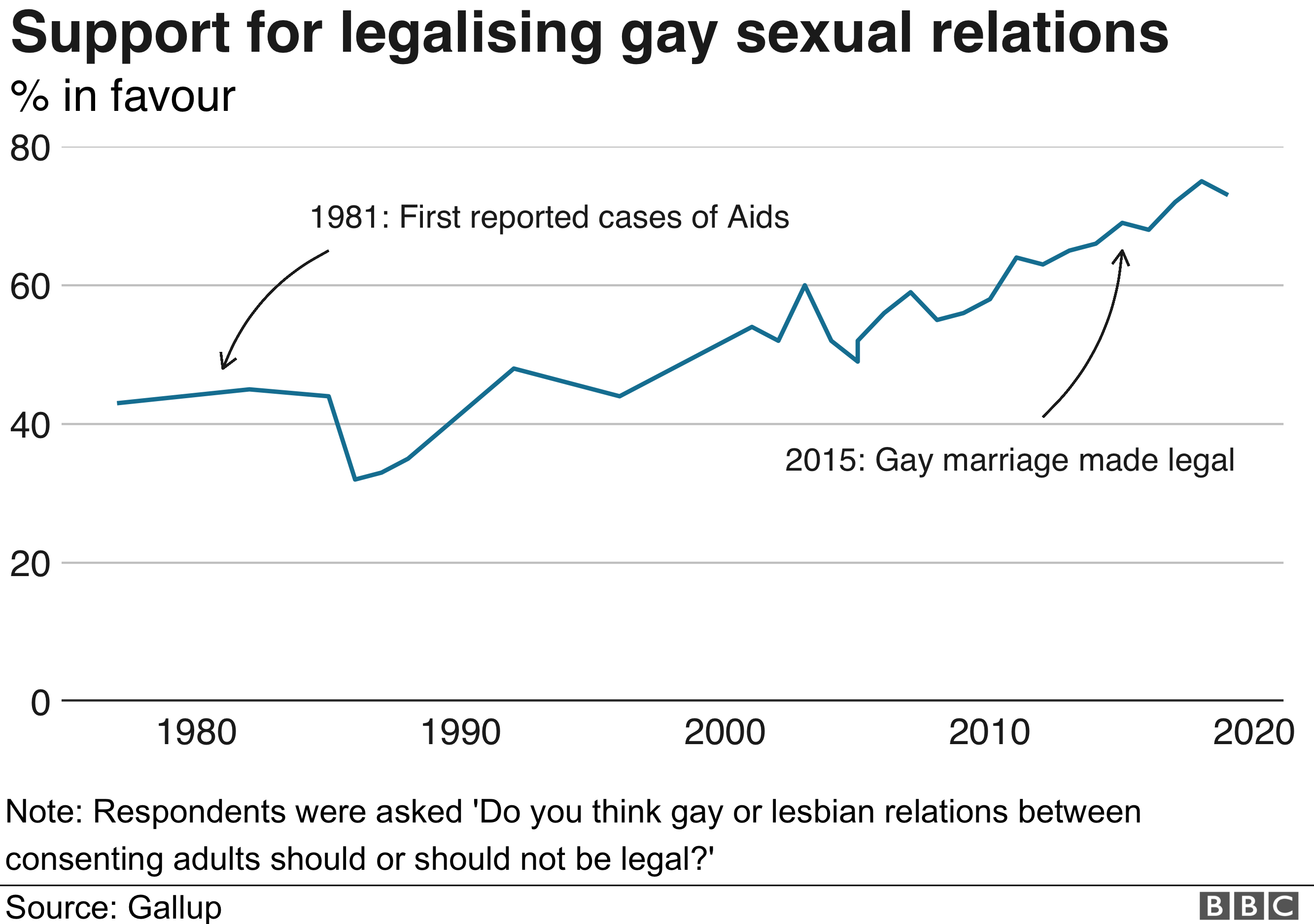

Many of the anti-sodomy laws were struck down in the 1980s, making homosexuality effectively legal, although it was decades before gay marriage became a federally-recognised right in 2015. The legal progress was matched by a change in attitudes – three-quarters of Americans are today accepting of gay relations.

In 2019, there are still battles to fight – gay people can still be fired from their jobs in many states. And campaigners say the Trump administration is taking the country backwards again by rolling back some of their hard-fought freedoms.

But the arrival of the first openly gay candidate for president suggests the general direction of travel is still one way. Perhaps the biggest sign of progress is that it’s Pete Buttigieg’s unusual surname and his Norwegian language skills that seem to provoke more curiosity than his sexuality.

No one who was fighting the police that night or marching on the streets could have predicted the strides made since. It’s therefore worth reflecting on how much came out of that police raid on a Mafia bar, says David Carter, author of Stonewall: The riots that started a revolution, a book which is regarded as the definitive account of what happened.

“It’s very unexpected and very rare in human history that something that’s a totally spontaneous act changed the course of human history for the better.”

It wasn’t the first gay uprising against the police – as the LA Times recently recalled, the police were pelted with donuts 10 years earlier – but it was the most consequential.

“It went from being microscopic in size to a mass movement – that’s the historical significance of Stonewall,” says Carter. But it has a deeper meaning too, he thinks. “These moments take on inspirational meaning so in terms of US history it’s when MLK was giving his ‘I have a dream’ speech at the Lincoln Memorial. It’s the Marines raising the flag over Iwo Jima.”

But unlike the other famous stories, the story of Stonewall is not taught in many schools. It is, however, remembered in other ways – in film, book and even in heritage. In 2016, the area around Stonewall was designated a national monument, and last week, the New York Police Department apologised for the raid.

What Mark did next

So what happened to Mark Segal, the teenager handed the chalk by his friend Marty?

When the Stonewall was raided, he had only been in New York for six weeks and was staying at the YMCA for $6 a night. Defiance was nothing new to him – his first act of rebellion was as a young Jewish boy refusing to sing Onward Christian Soldiers at school in Philadelphia. His grandmother had taken him to his first civil rights rally when he was 13.

And outside Stonewall that night, he thought: “We are fighting for our rights, just as women, African Americans and others had throughout history.” The police that night were a symbol, he says. “They were the synagogue, the family I couldn’t tell, the reason I had to leave the city I loved to move to New York. They represented religion, the media, the government. All the people that shoved us away.”

But Stonewall wasn’t just a fight, it was a spirit and it gave him a purpose, he says. He vowed to spend the rest of his life on a new vocation. It took him first to the GLF where he helped run their youth outreach. And he also took on another mission – to make gay people as visible as possible to mainstream America. He did this through a strategy of public disruption. Or, as they were known, “zaps”.

In 1973, he crashed the CBS primetime news show hosted by broadcasting legend Walter Cronkite and watched by 60 million people, holding a placard saying: “Gays protest CBS prejudice”.

He went on to launch a gay newspaper in Philadelphia and become a pioneer in gay journalism, and his work on equality earned him an audience with President Barack Obama.

Before he was given that piece of chalk 50 years ago, as a penniless teenager, he could never have imagined the path ahead – in the country or in his own life.

“I wouldn’t have known I would one day be dancing with my husband in the White House. So what I would say to someone who’s young and thinking of coming out is ‘Dream big’.”

.

Source: Read Full Article