Robert Mugabe: From liberator to tyrant

Robert Gabriel Mugabe was a man who divided global public opinion like few others.

To some, he was an evil dictator who should have ended his days in jail for crimes against humanity.

To others, he was a revolutionary hero, who fought racial oppression and stood up to Western imperialism and neo-colonialism.

On his own terms, he was an undoubted success.

First, he delivered independence for Zimbabwe after decades of white-minority rule.

He then remained in power for 37 years – outlasting his greatest enemies and rivals such as Tony Blair, George W Bush, Joshua Nkomo, Morgan Tsvangirai and Nelson Mandela.

And he destroyed the economic power of Zimbabwe’s white community, which was based on their hold over the country’s most fertile land.

However, his compatriots – except for a small, well-connected elite – paid the price, with the destruction of what had once been one of Africa’s most diversified economies.

In the end, this came back to haunt him.

The outpouring of joy on the streets of Harare which greeted his forced resignation in November 2017 echoed the jubilation in the same city 37 years earlier when it was announced he was the new leader of independent Zimbabwe.

Although he was allowed to see out his days in peace in his Harare mansion, it was not the end he wanted, having famously boasted: “Only God, who appointed me, will remove me.”

Many Zimbabweans trace the reversal of his – and their – fortunes to his 1996 wedding to his secretary Grace Marufu, 41 years his junior, following the death of his widely respected first wife, Sally, in 1992.

“He changed the moment Sally died, when he married a young gold-digger,” according to Wilf Mbanga, editor of The Zimbabwean newspaper, who used to be close personal friends with Mr Mugabe.

That sentiment was common long before anyone dreamed she might one day harbour presidential ambitions, which were the trigger for his close allies in the military and the ruling Zanu-PF party to oust Mr Mugabe from power.

Mugabe the man

While he was sometimes portrayed as a madman, this was far from the truth. He was extremely intelligent and those who underestimated him usually discovered this to their cost.

Stephen Chan, a professor at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, noted Mr Mugabe had repeatedly embarrassed the West with his “adroit diplomacy”.

Mugabe in his own words:

“Cricket civilises people and creates good gentlemen. I want everyone to play cricket in Zimbabwe; I want ours to be a nation of gentlemen” – undated

“Let the MDC and its leadership be warned that those who play with fire will not only be burnt, but consumed by that fire” – 2003 election rally

“We are not hungry… Why foist this food upon us? We don’t want to be choked. We have enough” – interview with Sky TV in 2004, amid widespread food shortages

“Don’t drink at all, don’t smoke, you must exercise and eat vegetables and fruit” – interview on his 88th birthday in 2012

“[Nelson] Mandela [South Africa’s first black president] has gone a bit too far in doing good to the non-black communities, really in some cases at the expense of [blacks]… That’s being too saintly, too good, too much of a saint” – 2013 state TV interview

As a former political rival of Mr Mugabe, who went on to serve as his home affairs minister, Dumiso Dabengwa witnessed the different sides of Zimbabwe’s founding father.

“Under normal circumstances, he would be very charming but when he got angry, he was something else – if you crossed him, he could certainly be ruthless,” he told the BBC before his death in May 2019.

Mr Dabengwa said the president would often let him win an argument over policy during the decade they worked together, or they would agree to compromise – not the behaviour of a dictator.

But something, he added, changed after 2000 and Mr Mugabe resorted to threats to ensure he got his way.

“He held compromising material over several of his colleagues and they knew they would face criminal charges if they opposed him.”

This is not a picture recognised by Chen Chimutengwende, who worked alongside Mr Mugabe in both the Zanu-PF party and government for 30 years.

“In all the time I have worked with him, I have never seen him be vindictive or ill-treat anyone,” he said.

Wilf Mbanga, editor, The Zimbabwean:

“He went from trying to convince you with his arguments to a man who would send his thugs to beat you up if you disagreed with him”

Watch: Wilf Mbanga on his friend Robert Mugabe

Mr Chimutengwende felt Zimbabwe’s leader had been unfairly demonised in the Western media because of his policy of seizing land from white farmers whom he suspects of having influential supporters, especially in the UK, where many trace their roots.

Mugabe the teacher

The year 2000 marked a watershed both in the history of Zimbabwe and the career of Mr Mugabe.

Until then, he was generally feted for reaching out towards the white community following independence, while Zimbabwe’s economy was still faring pretty well.

After coming to power in 1980, Mr Mugabe greatly expanded education and healthcare for black Zimbabweans and the country enjoyed living standards far higher than its neighbours.

In 1995, a World Bank report praised Zimbabwe’s rapid progress in the fields of health and literacy. Run by a former teacher, the country had the highest literacy rates in Africa.

In her book, Dinner With Mugabe, Heidi Hollande said Mr Mugabe used to personally coach illiterate State House workers to help them pass exams.

Mr Mbanga recalls listening to the songs of US country singer Jim Reeves together.

“He could be very affectionate, he was an intellectual. He liked explaining things, like a teacher,” said Mr Mbanga, but then saw a huge change in his former friend.

“He went from trying to convince you with his arguments to a man who would send his thugs to beat you up if you disagreed with him.”

In fact, the warning signs were already there – the massacre of thousands of ethnic Ndebeles seen as supporters of Mr Mugabe’s rival, Joshua Nkomo, in the 1980s and the start of the economic decline – but these were usually overlooked.

“Some say he had us all fooled, I am convinced he himself changed,” Mr Mbanga said.

The journalist says that in his early years as president, Mr Mugabe genuinely believed in trying to improve the lives of his people, and introduced a “leadership code” which barred ministers from owning too much property.

“Look at him today, he is fabulously wealthy. He is not the person I knew,” Mr Mbanga said in May 2014.

‘Political calculator’

In February 2000, the government lost a referendum on a draft constitution.

With parliamentary elections looming four months later and a newly formed opposition party with close links to the “No” campaign posing a serious threat, Mr Mugabe unleashed his personal militia.

Some were genuine veterans of the 1970s war of independence but others were far younger.

TV footage of white farmers queuing up to make donations to the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) meant Mr Mugabe was able to portray the opposition as stooges of the white community, and by extension the UK.

The invasion of white-owned farms achieved several goals for Mr Mugabe and his allies:

There was certainly a strong moral argument that land reform was needed in Zimbabwe but the way it was carried out was undoubtedly with political motivations uppermost.

Despite the widespread violence, intimidation and electoral fraud, the MDC gained almost as many elected seats as Zanu-PF in 2000.

Had it not been for the intimidation in rural areas, Zanu-PF may well have lost its majority.

Lovemore Madhuku, one of the leaders of the “No” campaign in 2000, described Mr Mugabe as an “an excellent political calculator”, who adapted his tactics to the situation.

“There are moments when he chooses to be ruthless, others when he chooses to be magnanimous… He considers what is best – for him – in every situation and reacts accordingly,” Mr Madhuku told the BBC.

He said Mr Mugabe might not have realised the damage the seizure of white-owned land would do to Zimbabwe’s economy but in any case, he would not have cared, as long as he remained president.

Mr Chan agreed that, “in terms of Mr Mugabe’s value-set, the ownership of the land is more important than the smooth running of the economy”.

And the economy continued to decline until 2008.

After 28 years of Mr Mugabe’s rule, the resourceful, largely self-sufficient country lay in ruins. The inflation rate had reached an unfathomable 231 million per cent and young Zimbabweans were voting with their feet, fleeing the country he had fought to liberate.

And yet, from this low point, he once more managed to outmanoeuvre his rivals and remain in power for another nine years.

‘Mummy’s Boy’ to African liberator

The key to understanding Robert Mugabe is the fight against white-minority rule.

In the Rhodesia where he grew up, power was reserved for some 270,000 white people at the expense of about six millions Africans.

A host of other laws discriminated against the black majority, largely subsistence farmers.

They were forced to leave their ancestral land and pushed into the country’s peripheral regions, with dry soil and low rainfall, while the most fertile areas were reserved for white farmers.

Reclaiming the land was one of the main drivers behind the 1970s war which brought Mr Mugabe to power.

The son of a carpenter who abandoned his family, as a child Mr Mugabe was said to have been a loner, who spent much of his time reading.

Ms Hollande wrote that after his elder brother died of poisoning when Mr Mugabe was just 10, his mother became depressed and the young Mugabe would do everything he could for her, to the extent he was teased as a “mummy’s boy” at school.

He eventually qualified as a teacher and in 1958 went to work in Ghana, which had just become the first African country south of the Sahara to end colonial rule.

Encouraged by his Ghanaian wife, Sally, and the pan-Africanist speeches of Ghana’s leader Kwame Nkrumah, Mr Mugabe became determined to achieve the same back home.

On his return in 1960, he started to campaign for an end to discrimination and was jailed for a decade after being convicted of sedition.

While in prison, his supporters wrested control of Zanu, the biggest party fighting white rule, and installed him as leader.

On his release, he was supposed to remain in the country but with the help of a white nun, he was smuggled over the border into Mozambique and the Zanu guerrilla camps.

‘He loves power’

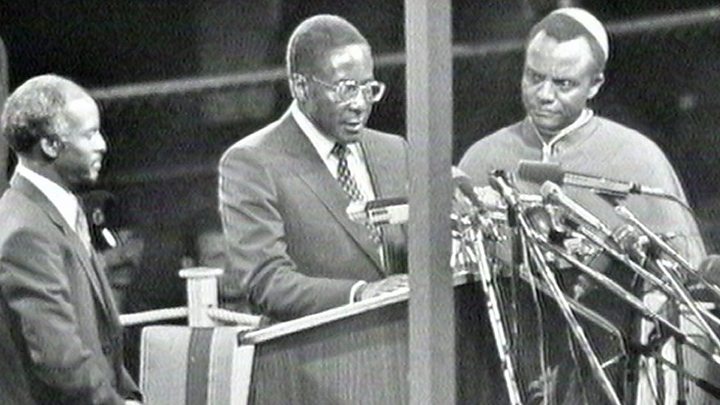

After Mr Mugabe won the 1980 elections which led to independence, he pursued a policy of reconciliation with the white community despite the bitterness built up during the war.

In a national address after becoming prime minister, he declared: “If you were my enemy, you are now my friend. If you hated me, you cannot avoid the love that binds me to you and you to me.”

Four faces of Mugabe:

Before independence:

“He was a very nice guy. At that stage, he was not too sure of himself. There were very strong people in Zanu who were not afraid to oppose him. He would never take a decision on his own” – Dumiso Dabengwa

1980-90:

“He did everything he could to improve the lives of his people. He wanted education for all. He wanted health for all. He introduced a leadership code limiting Zanu-PF cadres to 50 acres of land” – Wilf Mbanga

1990-2000:

“I worked very harmoniously with him and discussed issues. He would let me have my way or we would reach a compromise” – Dumiso Dabengwa

2000 – 2017:

“After 2000, he started flexing his muscles. He brought in people who he could influence. Several people were compromised – he held something over them” – Dumiso Dabengwa.

“He has become fabulously wealthy. He is not the person I knew. He changed the moment Sally died [in 1992], when he married a young gold-digger [Grace Mugabe]” – Wilf Mbanga

He allowed Ian Smith, the Rhodesian prime minister who had once declared that black people would not rule the country for 1,000 years and who reportedly personally refused to let Mr Mugabe leave prison for the funeral of his then only son, to remain both an MP and on his farm.

At this point, according to Mr Madhuku, Mr Mugabe’s hold on power was relatively weak, so he realised he had to reach out to his former enemies.

Former home affairs minister Mr Dabengwa said Mr Mugabe was even less self-confident earlier on in his political career.

“When I first met him in the 1960s, he was not sure of himself, of his position in Zanu,” Mr Dabengwa recalled.

“There were very strong people in Zanu who were not afraid to oppose him. He would never take a decision on his own but would always check with them first.”

But slowly, he consolidated control – first over the party which led the war against white-minority rule and later the country as a whole – until the point where his was the only voice that counted.

“He loves power, it’s in his DNA,” said Mr Madhuku.

Bonds forged in war

Throughout his time as president, his closest allies were always those with whom he had endured the hardships of life during the guerrilla war of independence.

When they felt their grip on power, and its trappings, were threatened, they reverted wholeheartedly to the conflict mentality.

“We are in a war to defend our rights and the interests of our people. The British have decided to take us on through the MDC,” he told a 2002 election rally.

This meant opposition supporters were denounced as traitors – a label which could mean an immediate death sentence.

Mr Chimutengwende argued that the scale of the violence was exaggerated and in any case sought to distance it from Mr Mugabe: “It is not the leader who throws a stone, or asks his followers to throw a stone.”

But Mr Dabengwa, the minister in charge of the police in 2000, said Mr Mugabe’s Zanu party had been using such methods since the 1980 election.

He said that fighters from Zanu’s armed wing had been sent out into rural areas to ensure villagers voted the “right” way, partly through all-night indoctrination sessions, known as “pungwes”.

“People were told there were magic binoculars which could tell which way they voted and there were no-go areas for other parties,” said Mr Dabengwa, whose Zapu party came a distant second in 1980.

“But the British declared those elections free and fair and so Zanu learnt that that was how to win an election.”

Although he won those elections in 1980, and formed a coalition government with Zapu, the underlying tensions burst into open violence just two years later.

Zapu leader Joshua Nkomo was accused of plotting a coup and the army’s North Korea-trained Fifth Brigade was sent to his home region of Matabeleland.

More than 20,000 people were killed in Operation Gukurahundi, which means “the early rain which washes away the chaff”.

At the time, South African double-agent Kevin Woods was making daily reports in person to then Prime Minister Mugabe for the internal security force, the Central Intelligence Organisation.

“He obviously wanted to know exactly what Fifth Brigade was doing,” he wrote in his autobiography.

In the end, a subdued Mr Nkomo once more agreed to share power with his enemy in order to end the violence in his home region – a forerunner of what later happened to the MDC.

Mugabe timeline

21 February 1924: Born

1964: Jailed after being convicted of sedition

1973: Becomes Zanu leader

1980: Becomes prime minister of Zimbabwe

1987: Becomes president under new constitution agreed under deal to end Matabeleland massacres

1992: Wife Sally dies

1996: Marries Grace Marufu

2000: Loses referendum, land invasions begin

2002: Wins presidential election amid widespread violence and fraud allegations

2005: Launches Operation Murambatsvina (Drive Out Rubbish), which forces 700,000 urban residents from their homes – seen as punishment for opposition supporters

2008: Comes second in election, violence leads his opponent Morgan Tsvangirai to withdraw from run-off

2009: Forms coalition government

2013: Resoundingly re-elected, Tsvangirai returns to opposition

2017: Forced to resign after army seizes power

6 September 2019: Dies in Singapore, which he visits for hospital treatment

Before he was finally ousted, his political low point was in 2008, when MDC leader Morgan Tsvangirai beat him in a presidential election, although not by enough for outright victory, according to the official results.

There were numerous reports Mr Mugabe was on the verge of resigning, although Mr Madhuku said he did not believe them, as the president subsequently demonstrated his determination to remain in power.

Again, a setback led to a sustained campaign of violence against his “enemies”.

The army and Zanu-PF militias attacked MDC supporters around the country, killing more than 100 and forcing thousands from their homes.

It became obvious that Zanu-PF would not relinquish its grip on power and Mr Tsvangirai withdrew from the second round, saying it was the only way to save lives.

Zimbabwe’s economy continued its freefall, reaching its nadir when people were dying from cholera in Harare because the country did not have the foreign currency to import the necessary chemicals to treat the water.

Under intense pressure, Mr Mugabe agreed to a coalition government with his long-time rival and, under MDC stewardship, the economy recovered.

But Prime Minister Tsvangirai was severely tarnished by working with Mr Mugabe – the president always managed to keep real power for himself and his allies.

By the time of the 2013 election, Mr Mugabe did not need to resort to extreme violence to win easily. He had once more demonstrated his remarkable skills of political survival and he remained in power until he was forced out in 2017.

Love-hate relationship with the UK

Mr Mugabe justified the 2000 land invasions by saying the UK’s Labour government, in power since 1997, had reneged on a British promise to fund peaceful land reform.

While it might be expected that an avowedly Marxist liberation fighter would have more in common with the Labour Party than the Conservatives, the opposite turned out to be true.

Robert Mugabe:

“Mrs Thatcher, you could trust her. But of course what happened later was a different story with the Labour Party and Blair, who you could never trust”

Under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the UK accepted that as the former colonial power, it had the moral duty to help finance the process of buying white-owned land and redistributing it to black farmers.

But after a report found the process had been tainted by cronyism, British funding was put on hold.

The new Labour government took matters further and declared: “We do not accept that Britain has a special responsibility to meet the costs of land purchase in Zimbabwe.”

In 2013, Mr Mugabe observed: “Mrs Thatcher, you could trust her. But of course what happened later was a different story with the Labour Party and [former Prime Minister Tony] Blair, who you could never trust.

“Who can ever believe what Mr Blair says? Here we call him Bliar.”

Despite the vitriol directed at the UK from 2000 onwards, Mr Mugabe was in some ways the epitome of an English gentleman.

He was usually turned out in immaculate, dark, three-piece suits and ties – until he was given a makeover in 2000 and advised to campaign in brightly coloured cloth emblazoned with his own face, like many other African leaders.

Visitors to State House were always offered tea to drink and he was a huge fan of cricket.

“Cricket civilises people and creates good gentlemen. I want everyone to play cricket in Zimbabwe; I want ours to be a nation of gentlemen,” he once said.

‘Beaten Christ’

He was educated by Jesuits in the Katuma mission near his birthplace in Zvimba, north-west of Salisbury (now Harare), where he was taken under the wing of an Irish priest, Jerome O’Hea.

This is presumably where he developed his abstemious nature – he did not drink alcohol or coffee and was largely vegetarian.

Wilf Mbanga:

“If he had died after 10 years in power, he would have been my hero forever”

His second wife Grace said he used to wake up at 05:00 for his exercises, including yoga.

This healthy lifestyle was no doubt one reason why he lived until the age of 95.

For many years, his health was a constant source of speculation.

A 2008 US cable quoted in Wikileaks suggested Mr Mugabe had been diagnosed with cancer, giving him between three and five years to live.

This prognosis turned out to be false, and on his 88th birthday Mr Mugabe joked he had “beaten Christ” because he had died and been resurrected so many times.

‘Spoilt legacy’

While he was vilified in the West, his anti-colonial rhetoric did strike a chord across Africa, even among many who condemned his human rights record.

At the 2013 memorial service in Soweto for Nelson Mandela – who replaced Mr Mugabe as Africa’s most admired anti-colonial fighter – Zimbabwe’s president was wildly cheered by the young South African crowd, even as they booed their own then leader, Jacob Zuma.

“A lot of people think that pan-Africanism is a thing of the past but that is not true,” said Mr Mugabe’s staunch ally, Chen Chimutengwende.

“While imperialism and racism exist, pan-Africanism is still needed,” he told the BBC.

But Zimbabwean journalist Wilf Mbanga said that in his latter years, Mr Mugabe had far more support outside his home country than within.

“Those young South Africans who praise him do not have to live under his rule,” he said, pointing out that many Ghanaians had less than fond memories of life under pan-African hero Kwame Nkrumah, who had inspired Mr Mugabe.

So how will Mr Mugabe be remembered?

Mr Chan said that until 2000, Mr Mugabe had a “good report card”, although the verdict later turned to “disastrous”.

“If he had died after 10 years in power, he would have been my hero forever,” said Mr Mbanga.

“But look at the schools and hospitals now.

“He has spoilt his legacy. Now, people will remember him for driving people out of Harare, Gukurahundi, election violence and everything else.”

Joseph Winter was the BBC’s Zimbabwe correspondent from 1997 until he was expelled in 2001

Source: Read Full Article