Remembering the lost Jews of Sudan

A recent call by a minister in Sudan’s new government for Jewish people to return to the country and reclaim citizenship has shone a light on a small but once-thriving community. Oral historian Daisy Abboudi, herself descended from Sudanese Jews, has been talking to members of the community and collecting their photographs.

David Gabra can still remember the exact date he left Sudan. “Twenty fifth of May 1965,” he said with certainty when talking about his departure.

At that time, things were getting increasingly difficult for Jewish people because of growing anti-Semitism.

“There was chaos… I remember one time we closed ourselves up in our home, and they were throwing stones at us, at our home.”

David decided he could no longer stay in the country.

Rapid rise, rapid decline

“I closed my [textile] store at nine o’clock at night as usual, I told my friends, my neighbours: ‘See you in the morning.’ And then I went straight to the airport and went to Greece.”

From there he went to Israel.

David’s departure was part of a movement of Jewish people that saw a community thought to have numbered 1,000 just a few years earlier reduced to just a handful by 1973.

That was the result of a changing political situation in Sudan from 1956. A rising anti-Israel sentiment meant most Jews no longer felt safe there.

This rapid decline mirrored its rapid growth just a few decades earlier.

The majority of the Jewish community was descended from those who arrived in Sudan in the early 20th Century, but there was a small Jewish presence in the country even before that.

In 1908, Moroccan-born Rabbi Suleiman Malka arrived in Khartoum with his wife and two eldest daughters at the request of the Jewish authorities in Egypt, which oversaw the community in its southern neighbour.

In a family portrait taken in the early 1920s, Rabbi Malka is seen next to his wife Hanna and surrounded by some of his children and grandchildren. He wears clothing traditional to the region – an open robe, called a jubba and a second robe underneath, known as an entari. He favoured these clothes throughout his life, though the rest of his family and the community opted for a more Western style.

The rabbi came to minister to the small older community as well as a growing number of Jews coming from across the Middle East, including Egypt, Iraq and Syria. They arrived on the new railway line built by British colonialists, connecting Alexandria in Egypt with Khartoum.

Many were small-time merchants trading goods like textiles and gum arabic – an important food additive made from Sudan’s acacia trees. Settling along the Nile in the four towns of Khartoum, Khartoum North, Omdurman and Wad Medani, 200km (125 miles) south of the capital, their businesses soon began to flourish.

Rabbi Malka died in 1949 and it took seven years to find a suitable replacement in the shape of Rabbi Massoud Elbaz, who arrived from Egypt in 1956.

A photograph of the family in 1965, taken just before they left Sudan, shows Rabbi Elbaz with his wife Rebecca and their five children.

“My father was a very simple, very modern rabbi. Very likable, always joking and everybody liked him a lot,” said Rachel, his eldest daughter, seated on the right of the photograph.

The community was deeply traditional although not overly observant, meaning that while they celebrated the festivals and kept some Jewish dietary laws, most lived largely secular lives.

Crammed in for weddings

As the community grew, it built a synagogue in Khartoum in 1926. Located on one of the central boulevards in the city and capable of holding up to 500 people, it was a clear statement of their new economic and social stability.

Weddings, symbolising the foundation of a new generation, were well celebrated at the synagogue.

“The whole community used to cram inside, one on top of the other. It was a big event,” explained Gabi Tamman, who now lives in Switzerland.

In this photograph, a guest at the marriage of Gabi to Lina Eleini in the synagogue in 1958 captured the intensity of the occasion as Rabbi Elbaz recited a blessing over wine.

Wedding-cake dress

While the synagogue was the spiritual home of the community, social life revolved around the Jewish Recreation Club.

Middle and upper class society in Sudan was comprised of many interlinked yet distinct groups. As well as the Jewish community, there were thriving Greek, Syrian, Italian, Egyptian, Armenian, British and Indian communities in Khartoum and Omdurman, its sister city across the River Nile. Each of these had a social centre, or “club”, in the capital, where they could meet, play cards, chat and socialise in the evenings.

Each December the various clubs would take turns to host a lavish ball, which was an opportunity to fundraise, show off and have fun with both colleagues and friends.

Flore Eleini, who is now 93 and living in Geneva, remembered them well.

“Anyone who wanted could go in a fancy-dress costume. It was like a masquerade ball and they had a prize for the winners. It was very nice.

“One time I went as a wedding cake. That became a famous costume.”

Cezar Sweid had his Bar Mitzvah, or coming-of-age ceremony, in 1958. A picture of the party following the ceremony at the Jewish Recreation Club that followed the ceremony shows him with his parents and some guests tucking into an elaborate chocolate cake.

Professional catering was extremely rare, and it usually fell to the women of the community to cook for these large family events.

“Everybody helped me with this Bar Mitzvah, all the women. We used to all be friends,” explained Frida Sweid, Cezar’s mother.

“One person is good with kibbeh [fried meat dumplings], so she did that, one is very good with qaiysat [a fried meatball encasing a boiled egg] so she did that, and so on.

“Then we had nine turkeys roasting on the spit at the end of our garden… and we brought them to the club, it was not far. We did it all together.”

Jewish children at Christian schools

The majority of the Jews in Sudan were fairly prosperous,so they generally socialised with the Sudanese elite and could pay for their children to attend private schools.

Children whose parents could not afford the fees were either subsidised by wealthier members of the community, or left school early to start work.

Nearly every Jewish boy attended Comboni College, which was a private Catholic school in Khartoum run by Italian priests.

Discipline was strict and competition encouraged. Jack Tamman (second from left) was snapped at school playing up to the camera with his classmates.

Jewish girls in Sudan had more choice. A popular alternative to the Catholic Sisters’ School was Unity High School, an English school based on Christian principles.

The photograph of the graduating class of 1948 sitting with British teachers shows the diversity of this part of Sudanese society at the time.

Margo Iskinazi (top left) was Jewish, while her classmates were Egyptian Copts, Armenian Christians, Greek Orthodox and Sudanese Muslims.

“It was so advanced,” Ruth Synett said reflecting on the standard of education at Unity High School, which she attended in the early 1960s.

“By the time I came to England [aged 10] I had already mastered geometry, algebra, all that stuff.”

Growing hostility

In 1956, following Sudanese independence and the Suez Crisis later that year, when Egypt was invaded by Britain, France and Israel, the mood in Sudan began to shift.

Support for the pan-Arabism of Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser grew. As a result of this and the anti-Israel rhetoric that it espoused, the atmosphere for Sudan’s Jews began to become more uncomfortable.

Jews were targeted in the press, falsely accused of being fifth columnists, and there were other signs of discrimination.

In 1956, a Jewish girl was attending a party with her parents when it was announced that there would be a competition to crown the next Miss Khartoum. She was shy, but reluctantly agreed to enter the beauty contest, which she won.

“From Miss Khartoum you got entered into Miss Egypt, but then they found out that she was Jewish and they took the title away from her,” her daughter, who wants to remain anonymous, explained.

From 1950 the community had been clubbing together to buy tickets for its poorest members to leave Sudan and start a new life in the recently established State of Israel.

By 1960, most of the Jews who were working in professions had also left the country and settled in either Israel, the UK, the US or Switzerland.

Those who owned businesses were the next to leave, although by that stage getting an exit visa was increasingly difficult.

By June 1967, when the Six Day War between several Arab countries and Israel broke out, only those members of the community who were most determined to stay in Sudan were still there.

By the end of the year only a handful of Jews remained, and most of them lived in Wad Medani, far away from the political heat of the capital.

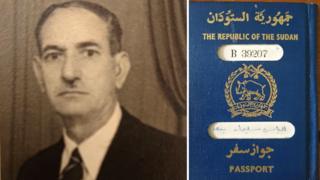

In 1973, Elias Benno, whose Sudanese passport is shown above, was one of the last Jews to leave Sudan. His ailing health meant he could no longer live by himself and so he finally made the decision to move to London, where he lived with his daughter Sara for one year before he died.

Despite this painful parting, the overwhelming majority of the Jews who lived in Sudan look back on their time there with affection.

Marianne Neumann’s voice cracked as she described sleeping outdoors.

“When you sleep on the roof, you can look up to the sky at night and because the air was so pure you could see thousands and thousands of stars, and you could smell the jasmine and gardenia from all the gardens… it was beautiful.”

Daisy Abboudi conducted the interviews for a forthcoming book on the history of Sudan’s Jewish community. More information is available on her website Tales of Jewish Sudan.

Source: Read Full Article