Cambodia’s unrepentant perpetrator of genocide

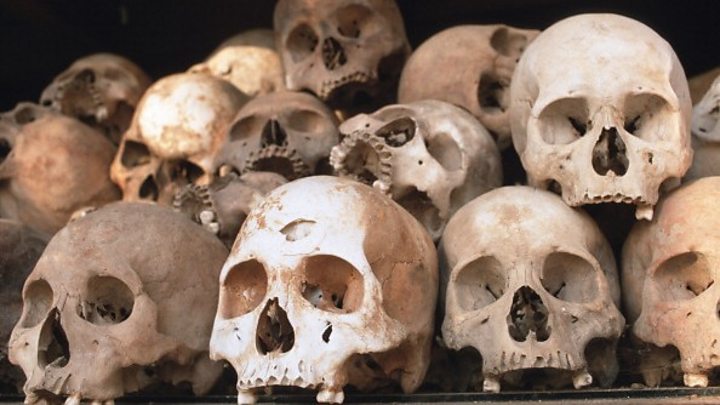

While Pol Pot has gone down in history alongside Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin and Mao Zedong as one of the most murderous leaders of the 20th Century, his right-hand man is less known.

But Nuon Chea, the mysterious “Brother Number Two” of the Khmer Rouge ultra-communists, was just as vital a cog within the regime’s killing machine that wiped out up to two million Cambodians.

He was perhaps even more instrumental.

Nuon Chea, who was seen by some experts as the brains behind policies that led to a quarter of his nation perishing, died in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh on Sunday. He was 93.

Despite being sentenced by a UN-backed tribunal to life in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity, he was defiant until the end – showing no remorse and refusing to accept responsibility for the crimes committed on his watch.

“If we had let them live, the party line would have been hijacked,” he once told Cambodian journalist Thet Sambath, referring to “traitors” in the regime.

“These were enemies of the people.”

Born in north-western Battambang province in 1926, Nuon Chea studied law in Thailand in the 1940s, where he was introduced to communist ideas.

Unlike Pol Pot and other Khmer Rouge leaders who discovered the works of Karl Marx and Josef Stalin in Paris, Nuon Chea did not study in France

He joined the Vietnamese-led Communist Party of Indochina in 1950 and returned to his homeland to take up arms in the fight against French colonialism.

Nuon Chea was appointed deputy secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, later known as the Khmer Rouge, late in 1960.

He held this position as the Khmer Rouge guerrillas overthrew the US-backed Lon Nol regime in 1975 and inflicted one of the most extreme social experiments the world has ever seen, transforming Cambodia into a brutal mass worksite.

“Nuon Chea was the alter ego of Pol Pot, and actually outranked him in the Communist Party Standing Committee during the first few years of the party,” said Craig Etcheson, a prominent historian of the Khmer Rouge.

“As the person primarily responsible for organisational matters and security in the party, it is arguable that he ultimately had more influence on the development and policies of the Khmer Rouge than did Pol Pot. It is certainly fair to say that he was at least equal to Pol Pot in his importance.”

Chea Sim, a Khmer Rouge official turned defector, explained in a 1991 interview how Nuon Chea laid out plans in 1975 for creating an agrarian socialist state, involving orders to “improve and “purify” the party ranks.

“This was a very important order to kill,” Chea Sim, who later became an influential politician in post-war Cambodia, said. “If people could not do it, they would be taken away and killed.”

By 1979, Nuon Chea was forced to flee back into the jungle as Vietnamese forces overthrew the Khmer Rouge. The world soon started to hear about the horrors the fanatical communists had inflicted on their people.

The Khmer Rouge still controlled areas of Cambodia for the next two decades and Nuon Chea was one of the last high-ranking leaders to surrender to the government in 1998. It took a further nine years before he was arrested on charges of crimes against humanity.

Despite this, “Brother Number Two” stayed unrepentant.

He argued that the vast majority of deaths were committed by Vietnamese-backed factions within the Khmer Rouge ranks. The party was “cleaved with deep factional divisions and plagued by internecine armed conflict,” Nuon Chea’s defence team at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal in Phnom Penh argued.

The judges disagreed. Nuon Chea and former Khmer Rouge head of state Khieu Samphan were sentenced to life in jail in two separate trials, first in 2014 for crimes against humanity and again in 2018 for genocide and other crimes. They are the only senior Khmer Rouge leaders to be prosecuted for the regime’s atrocities.

“Nuon Chea has no proof for blaming the ‘Vietnamese-backed units’ for the murders and deaths by deprivation….ascribed to him,” said Elizabeth Becker, an American journalist who interviewed Pol Pot in 1978.

In court Nuon Chea would regularly stare into space in his trademark sunglasses, emotionless as victims broke down in tears while remembering what the regime put them through. In his second trial, he would often watch proceedings on television from his holding cell due to ill health.

He would occasionally take the stand to rail against the court, supposed traitors or American imperialism, among other things.

Once he even claimed that the mass evacuation of Phnom Penh – including hospitals – within days of the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia in 1975 was done “out of kindness”.

“Throughout the trial Nuon Chea accepted no responsibility for anything and expressed no regrets,” said Ms Becker. “He was arrogant to the end.”

But while prosecutors at times struggled to prove a paper trail leading from the Khmer Rouge leadership to the crimes committed on the ground, plenty of evidence was presented to show that Nuon Chea signed off on atrocities.

Kaing Guek Eav, the former prison chief of Phnom Penh’s notorious S-21 torture centre and a man better known as Comrade Duch, laid many accusations at the feet of Nuon Chea, including that he personally ordered that Western inmates be burned to ash. Duch remains the only other person aside from Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan to be convicted by the Khmer Rouge Tribunal.

Many victims will be relieved that Nuon Chea was found guilty before he died, said Panhavuth Long, a legal expert and survivor of the Khmer Rouge.

“But people expected him to say more and the victims expected him to express regret… that he might apologise like Duch did.”

One of the few Cambodians who lit incense sticks in honour of Nuon Chea after hearing of his death was Thet Sambath, a journalist who would travel to the Thai border in the early-mid 2000s to interview the Khmer Rouge leader before he was arrested.

“He is responsible for some part [of the Khmer Rouge’s crimes] but not the whole thing,” Sambath, who lost his mother, father and brother at the hands of the regime, said from the US, where he now lives.

Despite the atrocities, Sambath said he came away from his hours of conversation with Nuon Chea believing that the ageing communist genuinely thought he was doing what was right for Cambodia.

“He always showed respect to me, he always called me nephew. The way he treated his grandchildren, he was very polite,” he said, fighting back tears.

But Youk Chhang, executive director of the Documentation Centre of Cambodia, who lost dozens of family members during the Khmer Rouge’s rule, said the history books would remember Nuon Chea in one way.

“He will be remembered by Cambodian history as evil,” he says. “This would satisfy many survivors. And it is justice for me as well.”

Source: Read Full Article